03/2023/XNUMX (

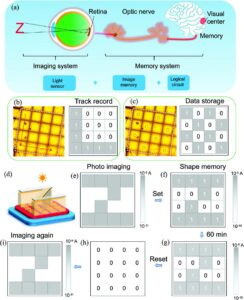

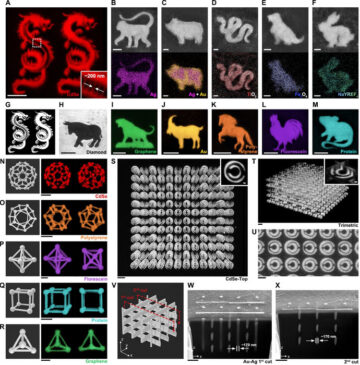

Tin tức Nanowerk) Cornell researchers used magnetic imaging to obtain the first direct visualization of how electrons flow in a special type of insulator, and by doing so they discovered that the transport current moves through the interior of the material, rather than at the edges, as scientists had long assumed.

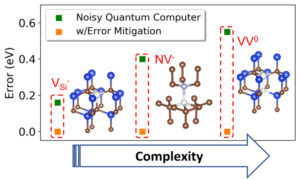

The finding provides new insights into the electron behavior in so-called quantum anomalous Hall insulators and should help settle a decades-long debate about how current flows in more general quantum Hall insulators. These insights will inform the development of topological materials for next-generation quantum devices.

The team’s paper published in

Vật liệu tự nhiên (

“Direct Visualization of Electronic Transport in a Quantum Anomalous Hall Insulator”). Tác giả chính là Matt Ferguson, Ph.D. ’22, currently a postdoctoral researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Physics of Solids in Germany.

The project, led by Katja Nowack, assistant professor of physics in the College of Arts and Sciences and the paper’s senior author, has its origins in what’s known as the quantum Hall effect. Được phát hiện lần đầu tiên vào năm 1980, hiệu ứng này xảy ra khi một từ trường tác dụng lên một vật liệu cụ thể để gây ra một hiện tượng bất thường: Phần bên trong của mẫu vật chất trở thành chất cách điện trong khi dòng điện di chuyển theo một hướng dọc theo mép ngoài. Các điện trở được lượng tử hóa hoặc giới hạn ở một giá trị được xác định bởi hằng số phổ quát cơ bản và giảm xuống XNUMX.

Một chất cách điện Hall dị thường lượng tử, được phát hiện lần đầu tiên vào năm 2013, đạt được hiệu ứng tương tự bằng cách sử dụng vật liệu được từ hóa. Sự lượng tử hóa vẫn xảy ra và điện trở dọc biến mất, đồng thời các electron chạy nhanh dọc theo rìa mà không tiêu tán năng lượng, hơi giống chất siêu dẫn.

Ít nhất đó là quan niệm phổ biến.

“The picture where the current flows along the edges can really nicely explain how you get that quantization. But it turns out, it’s not the only picture that can explain quantization,” Nowack said. “This edge picture has really been the dominant one since the spectacular rise of topological insulators starting in the early 2000s. Sự phức tạp của điện áp và dòng điện cục bộ phần lớn đã bị lãng quên. In reality, these can be much more complicated than the edge picture suggests.”

Only a handful of materials are known to be quantum anomalous Hall insulators. For their new work, Nowack’s group focused on chromium-doped bismuth antimony telluride – the same compound in which the quantum anomalous Hall effect was first observed a decade ago.

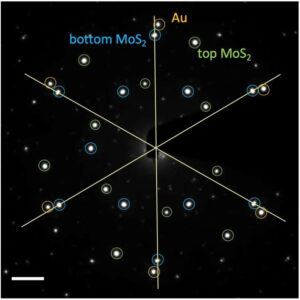

Mẫu được trồng bởi các cộng tác viên đứng đầu là giáo sư vật lý Nitin Samarth tại Đại học bang Pennsylvania. To scan the material, Nowack and Ferguson used their lab’s superconducting quantum interference device, or SQUID, an extremely sensitive magnetic field sensor that can operate at low temperatures to detect dauntingly tiny magnetic fields. The SQUID effectively images the current flows – which are what generate the magnetic field – and the images are combined to reconstruct the current density.

“The currents that we are studying are really, really small, so it’s a difficult measurement,” Nowack said. “And we needed to go below one Kelvin in temperature to get a good quantization in the sample. I’m proud that we pulled that off.”

When the researchers noticed the electrons flowing in the bulk of the material, not at the boundary edges, they began to dig through old studies. They found that in the years following the original discovery of the quantum Hall effect in 1980, there was much debate about where the flow occurred – a controversy unknown to most younger materials scientists, Nowack said.

“I hope the newer generation working on topological materials takes note of this work and reopens the debate. It’s clear that we don’t even understand some very fundamental aspects of what happens in topological materials,” she said. “If we don’t understand how the current flows, what do we actually understand about these materials?”

Answering those questions might also be relevant for building more complicated devices, such as hybrid technologies that couple a superconductor to a quantum anomalous Hall insulator to produce even more exotic states of matter.

“I’m curious to explore if what we observe holds true across different material systems. It might be possible that in some materials, the current flows, yet differently,” Nowack said. “For me this highlights the beauty of topological materials – their behavior in an electrical measurement are dictated by very general principles, independent of microscopic details. Nevertheless, it’s crucial to understand what happens at the microscopic scale, both for our fundamental understanding and applications.

- Phân phối nội dung và PR được hỗ trợ bởi SEO. Được khuếch đại ngay hôm nay.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Trao quyền cho chính mình. Truy cập Tại đây.

- PlatoAiStream. Thông minh Web3. Kiến thức khuếch đại. Truy cập Tại đây.

- Trung tâmESG. Ô tô / Xe điện, Than đá, công nghệ sạch, Năng lượng, Môi trường Hệ mặt trời, Quản lý chất thải. Truy cập Tại đây.

- BlockOffsets. Hiện đại hóa quyền sở hữu bù đắp môi trường. Truy cập Tại đây.

- nguồn: https://www.nanowerk.com/nanotechnology-news2/newsid=63455.php