Some people feel they are already living in the metaverse, given how much time they spend staring at screens and interacting with other humans via video conferences and chat groups. Others say we are way off the metaverse and the vision may never be realised.

I wanted to document some initial assumptions and hypotheses. For this post I’ll use “metaverse” very loosely and broadly to mean something like a multi-user virtual environment (island; planet; galaxy; etc) that can be accessed by an internet connected device (smartphone, computer, VR headset, whatever), perhaps with avatars, perhaps with some sort of economy.

At work, we are currently using the phrase “virtual worlds and experiences”. This seems broad enough, but then you might argue that Zoom is a virtual experience. But Zoom doesn’t feel very metaversey, at least to me, so it’s hard to draw bright-line boundaries. Maybe trying to define this isn’t a valuable use of time, given that meanings evolve with usage, and journalists and consultants love to overload buzzwords for fun and profit.

Metaverse is an adjective

To me right now, metaverse is a descriptor of a virtual world or environment. It’s an adjective (describing word), so it’s better to ask “How metaversey is this? And in what respects?” than to ask “Is this a metaverse, yes or no?”.

There are a number of dimensions to metaverseyness (yes I’m gonna keep making up words): What kind of metaverse/virtual world is it? How immersive is it? High fidelity or lo-fi? Persistent? Publicly accessible? Do my assets exist outside of it? Can anyone build inside it? Can a tech overload or a government boot users out? Is the flow of information controlled? Who gets to graffiti on the buildings?

But even asking questions like this implies some sort of definition of metaverse: if virtual world A is more photorealistic than virtual world B, does that mean A is more metaversey than B? This would imply that photorealism is a core metaverse characteristic. But we don’t know how important that is yet. I’m not sure that photorealism is that important to attract attention and users. After all, Minecraft and Roblox.

To this point: I’m not sure if I enjoyed Grand Theft Auto 1 more or less than the most recent one, or if I found one more compelling than the other, at time of playing them. Graphical quality by itself doesn’t imply how compelling something is or how much time I want to spend there.

While photorealism helps to describe a characteristic of a virtual world, it may not be a defining characteristic. It may not even be that important, depending on the context. We have to be careful that the questions we ask don’t imply some sort of canonical Platonic ideal of a metaverse. The business question, at least for investors, is “Where are people going to hang out and spend their attention?”.

At this stage I think I don’t think it’s important. Metaverse is whatever you want it to be, and changes depending on context.

Public and private metaverses

I see a divergence between public and private metaverses, just as we have public and private networks (“the internet” and intranets), and public and private blockchains (oh, boy).

As a side note, there’s no such thing as a universal “internet” experience. There are at least two internet experiences (China, Rest of World), which are quite different in character. And “Rest of World” may indeed split into “Europe” and “Not Europe” given the EU’s GDPR regime. Also there is the un-indexed internet (ie data that doesn’t appear in search results). The internet isn’t as universal as you may be led to believe, but as a model and analogy, it’s pretty good.

The adoption arc for private and public metaverses will play out differently.

Private metaverses have an owner and controller who is typically the developer of the virtual world. They are the gatekeeper of users, and allow people in and kick people out. They control the experience. Users trust the developer to behave in a certain way, just as we have been conditioned to trust application developers today. Developers may or may not allow 3rd parties to build inside, they may or may not allow 3rd parties to monetise (or take a huge cut!), they may be a platform or an aggregator, or neither.

These private metaverses can and will censor content and users (this is not necessarily a bad thing, it’s both a pro and a con). They will censor because they are a point of centralised control, they are run as businesses (not protocols), they have staff and shareholders, and nation states can put a gun to their head and say “do this”. So long as people exist physically and nation states have a monopoly on violence, any centralised organisation will have to censor – and the bigger they are, the more they censor because they have more at stake.

Blockchain blockchain blockchain! These private virtual worlds don’t need blockchains. Many of these shouldn’t use blockchains! Blockchains are useful when you want to promise your users some sort of persistence and guarantees over time. But if you are building a VR environment for surgeons to practice performing an uncommon surgical procedure, you don’t want persistence – you want to be able to restart the simulation again and again. Same for pilots and flight sims. Same, perhaps, with virtual classrooms or workplace meeting rooms. But then again, are these kinds of virtual experiences metaverses?

Public metaverses are more interesting. They are grungier, more libertarian. They have characteristics of unstoppability, censorship resistance at the core, (but more on this later), permissionless access for both users and developers / builders, composability, true digital asset ownership outside of the experience, and persistence. They need to use public blockchains as the independent, neutral, asset ownership ledger that is outside the control of the developers of the virtual world wrap. Some of the workings of the virtual worlds could even be written as smart contracts on public blockchains, making these virtual worlds more unstoppable, and reducing the reliance on specific developers.

Perhaps these public metaverses can be designed to be “survivable” (I just made that up, perhaps there’s a better word) such that if the developers of the wrap give up; another developer can pick it up, with the assets inside the wrap living on. A good question to ask may be “If your project failed, how much of the world & objects would survive for another group of developers to continue to build around?”

Hypothesis: I think that private metaverses will be successful! Especially in the short term: big tech companies understand human psychology, scalability, technology, gaming, etc, better than anyone else in the world, and they have the means to coordinate resources to build their vision. But they also have shareholders and must extract value for them – that’s the job of a company. Their KPIs are revenue, on-platform spend, user growth, time on platform, etc; so it is absolutely against their DNA to allow interoperability away. They want you to stay, not leave! And they don’t want you to be able take anything with you.

So their metaverses will absolutely be one-way walled gardens or trapdoors (they make it easy to come in but hard to leave), despite any narrative you might hear today. We see this easy-in, hard-out concept everywhere with the big tech platforms. They can’t help themselves, it’s part of the corporate construct. This means that their metaverses will likely be a new user interface (ooh, look, 3d!) to their existing products, services, and revenue models, but not a new business model or paradigm.

But in the longer term, perhaps public, permissionless, persistent metaverses could have a chance. Given a choice, and all else being equal, surely consumers would prefer an experience where they really own their assets, rather than having a corporation tell them that they own it unless the corporation decides otherwise? Surely consumers would prefer to hang out in an environment where they have had a say in the algorithms used to feed them information, rather than, say, Facebook or Twitter’s feed algos? Surely consumers would rather use a platform where they know if the developer fails, their “stuff” will work and have value elsewhere?

What about speed of development? Private metaverses can be built more quickly right now – a large tech company can dedicate hundreds of technical staff to coordinate and build out a vision. But once we have the primitives sorted out, the speed of development and innovation in public metaverses could eventually be faster than in private ones, as many teams with competing visions could be building on the same platform. Facebook can only build at the speed of Facebook engineers, and this process could be stymied by internal politics; Facebook can only innovate within its own constraints and KPIs (and don’t you dare cannibalise what’s already working!); Web3 can build at the speed of all the web3 projects combined, with commercial competition driving the advancements, and it can innovate in a lot more weird and wonderful directions.

Side note on decentralisation: The goal isn’t decentralisation for its own sake; decentralisation is a means to an end. To be clear: the goal is universal access and expression – “free speech”, if you want. To have free speech, you need censorship resistance. To have censorship resistance, you need the thing to be unstoppable. But it can’t be unstoppable if there is a central actor that can be coerced into stopping it (nation state gun to head, etc), So to allow for universal access and expression, you need to decentralise as much as possible. Put succinctly: Decentralisation is necessary for free speech.

One or many?

Will there be one winning virtual world, with many different continents/areas/venues for different use cases? Not likely. I think we’ll end up with a bunch of virtual worlds, just like we have a bunch of websites and apps today, and users will be able to hop between them just as we hop between apps and websites. They won’t all be joined up neatly in one unified experience (unless you consider the internet experience “unified”). There are just too many different use cases, communities, vibes, and technologies to think that everything will end up in one virtual world experience.

Different worlds will prioritise different things and will attract different user communities. There will be technological prioritisations, community prioritisations, user experience prioritisations, etc. Some worlds may be low fidelity, some high fidelity, some prioritise immersion, others prioritise social interactions, some will focus on certain hobbies or professions, etc etc. It’s hard to imagine everything being under one roof without a proliferation of differentiated competitors for our attention.

As users, we actually want different contexts. Imagine if Facebook, LinkedIn, Twitter, YouTube, Twitch, Discord, Telegram, Whatsapp, Instagram, etc etc were all accessible in one interface. Yuck! We wouldn’t know how to behave. Someone once told me “LinkedIn is the kids sitting at the front of the class leaning forwards with their hands up, Twitter is the kids at the back throwing spitballs at the teacher”. We all have our different sides to our personalities, and we all want to behave differently in different contexts.

On virtual land scarcity

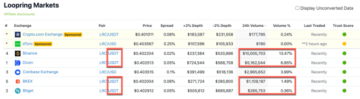

Surely if anyone can spin up a virtual world with more land, there is potentially infinite land available, so land shouldn’t be worth anything?

That’s not the right way of thinking about it. There are potentially infinite websites, yet some are more valuable than others. Why? It’s not scarcity of land, it’s scarcity of human attention and its concentration. If there is one virtual world where everyone is hanging out, and another virtual world where no one goes; which one do you think is more valuable. What are people talking about? Where are they hanging out? What are the social signals? Who can you flex to?

I guess we could call it the attention economy – we have to focus on what’s compelling and where will people spend their scarce attention, rather than the scarcity of the land or assets.

Other stuff

I also wanted to talk about interfaces, interoperability, censorship / filtering, and persistence, but will leave that to another post, this one is already long enough!

Next steps

On my reading list is Matt Ball’s The Metaverse book, Punk6529’s OM thread, and Jamie Burke’s Open Metaverse paper. Please let me know if there are other must-reads!

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- Platoblockchain. Web3 Metaverse Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- Source: https://bitsonblocks.net/2022/08/26/metaverse-musings-part-one/

- 1

- a

- Able

- About

- about IT

- absolutely

- access

- accessed

- accessible

- actually

- Adoption

- advancements

- After

- against

- algorithms

- All

- already

- and

- Another

- anyone

- appear

- Application

- apps

- Arc

- argue

- around

- asset

- Assets

- attention

- auto

- available

- Avatars

- back

- Bad

- because

- being

- believe

- Better

- between

- Big

- big tech

- bigger

- blockchain

- blockchains

- book

- boundaries

- broad

- broadly

- build

- builders

- Building

- built

- Bunch

- business

- business model

- businesses

- call

- careful

- cases

- Censorship

- Censorship Resistance

- central

- certain

- Chance

- Changes

- character

- characteristic

- characteristics

- China

- choice

- class

- clear

- combined

- come

- commercial

- Communities

- community

- Companies

- company

- compelling

- competing

- competition

- competitors

- computer

- concentration

- concept

- conferences

- connected

- Connected Device

- Consider

- constraints

- construct

- consultants

- Consumers

- content

- context

- contexts

- continue

- contracts

- control

- controlled

- controller

- coordinate

- Core

- Corporate

- CORPORATION

- could

- Currently

- data

- decentralisation

- dedicate

- Depending

- describe

- designed

- Despite

- Developer

- developers

- Development

- device

- different

- differentiated

- digital

- Digital Asset

- dimensions

- discord

- Divergence

- dna

- document

- Doesn’t

- Dont

- driving

- economy

- elsewhere

- Engineers

- enough

- Environment

- especially

- etc

- Ether (ETH)

- Even

- eventually

- everyone

- everything

- evolve

- existing

- experience

- Experiences

- extract

- Failed

- fails

- faster

- fidelity

- filtering

- flight

- flow

- Focus

- For Investors

- found

- Free

- Free speech

- front

- fun

- Galaxy

- gaming

- Gardens

- GDPR

- Give

- given

- goal

- Goes

- going

- good

- Government

- Group

- Group’s

- Growth

- guarantees

- Hands

- Hang

- Hard

- having

- head

- help

- helps

- High

- How

- How To

- HTTPS

- huge

- human

- Humans

- Hundreds

- I’LL

- ideal

- immersive

- important

- in

- independent

- information

- initial

- innovate

- Innovation

- interacting

- interactions

- interesting

- Interface

- interfaces

- internal

- Internet

- Interoperability

- Investors

- island

- IT

- itself

- Jamie

- Job

- joined

- Journalists

- Keep

- kick

- kids

- Know

- Land

- large

- Leave

- Led

- Ledger

- likely

- List

- living

- Long

- longer

- Look

- Lot

- love

- Low

- made

- make

- Making

- many

- max-width

- means

- meeting

- Metaverse

- metaverses

- might

- Minecraft

- model

- models

- monetise

- more

- most

- NARRATIVE

- nation

- Nation State

- necessarily

- necessary

- Need

- Neither

- networks

- Neutral

- New

- number

- objects

- ONE

- organisation

- Other

- Others

- otherwise

- outside

- own

- owner

- ownership

- Paper

- paradigm

- part

- parties

- People

- performing

- perhaps

- persistence

- Personalities

- Photorealistic

- Physically

- pick

- planet

- platform

- Platforms

- plato

- Plato Data Intelligence

- PlatoData

- Play

- playing

- please

- Point

- politics

- possible

- Post

- potentially

- practice

- prefer

- pretty

- prioritise

- private

- Private blockchains

- Pro

- process

- Products

- Profit

- project

- projects

- promise

- protocols

- Psychology

- public

- publicly

- put

- quality

- question

- Questions

- quickly

- Reading

- recent

- reducing

- regime

- reliance

- Resistance

- Resources

- REST

- Results

- revenue

- Roblox

- Rooms

- Run

- sake

- same

- Scalability

- Scarce

- Scarcity

- screens

- Search

- seems

- Services

- Shareholders

- Short

- Sides

- signals

- simulation

- Sitting

- smart

- Smart Contracts

- smartphone

- So

- Social

- some

- Someone

- something

- specific

- speech

- speed

- spend

- Spin

- split

- Staff

- Stage

- stake

- State

- States

- stopping

- such

- surely

- surgical

- survive

- Take

- Talk

- talking

- teams

- tech

- tech companies

- Tech Company

- Technical

- technological

- Technologies

- Technology

- Telegram

- The

- the world

- theft

- their

- themselves

- thing

- things

- Thinking

- Throwing

- time

- to

- today

- too

- true

- Trust

- Twitch

- typically

- Uncommon

- under

- understand

- Universal

- unstoppable.

- Usage

- use

- User

- User Experience

- User Interface

- users

- Valuable

- value

- via

- Video

- Virtual

- virtual land

- virtual world

- virtual worlds

- vision

- visions

- vr

- VR Headset

- Walled

- wanted

- Web3

- websites

- What

- which

- WHO

- will

- winning

- within

- without

- wonderful

- Word

- words

- Work

- workings

- Workplace

- world

- world’s

- worth

- would

- wrap

- written

- Your

- youtube

- zephyrnet

- zoom