It’s been a little over a decade since the original horror anthology V/H/S helped kickstart an entire era of horror, in which themed horror anthologies (The ABCs of Death, Tales of Halloween, Holidays, etc.) suddenly became underground hits — and a major proving ground for young directors showing off their chops to secure funding for full-length features.

Market oversaturation eventually slowed down the demand for these projects, but the OG, the V/H/S series, kept trucking along. 2013’s V/H/S/2 and 2014’s V/H/S: Viral were eventually joined by Shudder originals V/H/S/94 in 2021 and V/H/S/99 in 2022. And now, Shudder is streaming the latest in the series, V/H/S/85, a collection of five segments (one split up into a “wrapper” film connecting the others) all visually themed around 1980s found-footage technology.

This particular installment in the anthology series is sharper, more startling, and more impressive than some of the others, in part because of its all-star director lineup: V/H/S/94 and 99 producer David Bruckner (The Ritual, The Night House), Natasha Kermani (Lucky, Imitation Girl), Mike P. Nelson (Wrong Turn, The Domestics), Gigi Saul Guerrero (Culture Shock, Bingo Hell), and Scott Derrickson (Doctor Strange, The Black Phone).

All five directors were on hand at a Q&A after the movie’s world premiere at Fantastic Fest 2023, where Bruckner made a stir when he told the audience that he lured the other directors into the project by telling them “V/H/S movies are fuck-you movies,” a sentiment they all seemed to enthusiastically agree with. Naturally, when Polygon sat down with all five directors at Fantastic Fest, we had to explore what that means, both for the directors and for fans of the series.

Polygon: So what is a “fuck-you movie,” and why was getting to make one such an instant sell for all of you?

Gigi Saul Guerrero, director of “God of Death”: It means a project where you’re not afraid to push yourself as a filmmaker, but also to push yourself with things that you know you won’t be able to do on a regular job. [laughs] One that gives you an opportunity to not be afraid to shock audiences. Not afraid to leave them with something disturbing that lasts. And to actually grab something that maybe scares you personally as well.

Mike P. Nelson, director of “No Wake”/”Ambrosia”: So often, when you’re given a more normal movie or commercial, you get asked to pull back. And this one was the opposite. It was like, “No, go full-bore, and just have fun with it.”

Guerrero: No filter!

Natasha Kermani, director of “TKNOGD”: Permission to be a little mean and ugly.

Scott Derrickson, director of “Dreamkill”: It’s an opportunity to really swing for the fences without the fear of a big feature failure that will ruin your career. It’s very liberating to be able to do that.

David Bruckner, director of “Total Copy”: When you’re working on a feature, especially in studio systems, it’s a little bit like steering an aircraft carrier. There can be a lot of voices, there can be a lot of expectation. There’s a lot to uphold when you have three acts at work, you have to hold an audience’s attention for 90 minutes or more. It’s an enormous ask.

And part of this is that these are weird little haunted relics. They’re tapes that have been discovered at a certain point, so anything can happen. You don’t have to be as structured. And you find yourself asking different questions on setup. It’s a very purified state of mind: What do I want to see right now? No holds barred. And that’s refreshing for me. Invigorating.

Natasha, you made that point at the Q&A about being excited to make “ugly” movies for once, and that’s something else everyone here lit up over. Why is it inspiring to be able to do something ugly?

Kermani: I think we all love film language. Every single filmmaker here is a master of their craft. And I think a lot of times, there is that idea that whatever “beautiful” means, that film language is necessary for a commercial-quality film. With V/H/S/85 in particular, Scott talked a lot about how the medium is the message, letting us go into this really gritty visual place. “Glitch” was one of our keywords.

My DP cried when she saw the final version of our film. [laughs] She’s like, You can’t see anything! Like, yeah, it’s VHS, so you can’t see shit. So I think that really letting go — the actors may look kind of crazy. You’re gonna have moments where some part of the screen just drops off into black, there’s no detail there. I think embracing the ugly, the grit, the nastiness was very fun. Because normally we’re doing the opposite. How can we make this star look beautiful? So that’s liberating.

Guerrero: It’s just [about] not being perfect. We think a lot about framing and that polished look. With found footage, it has to feel so natural with the actors, with the camera. That’s why we do block, rehearse, shoot. But these films are just, Fucking make it and see what happens. So it feels natural. But definitely, I think all of our cinematographers had a lot of trauma after this. It’s hard on them to not be perfect with how they film anything.

Derrickson: Brett [Jutkiewicz], who shot The Black Phone for me, one of the reasons he said yes to this was because I said I thought we should just use ’80s cameras, and shoot everything analog. And he got very excited about that. And Super 8 footage, which I integrated into this in an attempt to mess with the format of the V/H/S franchise.

So when you talk about “ugly,” it’s a beautiful ugliness. It’s everything people are trying not to have in their visual images now. Higher resolution, more clarity, perfect brightness — we all grew up watching things in low-res, and there’s absolutely a beauty to that. And not as a nostalgic thing, but an actual capturing of what cameras at that time did was really interesting to me.

Nelson: I was trying to get the look of the way home movies were shot back then, as opposed to how they are today. Even with camera phones, people will do cool angles and put them on little gyros. But I was so inspired by my dad’s old stuff. He had one of the old Magnavox cameras that was shoulder-mounted, that was connected to a VCR he had to carry around. And he had to make sure the battery was charged, and it only lasted maybe an hour.

I loved watching how he shot things, because it was a very new medium for the consumer. People were shooting in Super 8 and 16mm prior to this, home movies, but this was this new thing. The cameras were giant. One of the shots that always kills me — it’s like literally in every home movie of the time, whether it was Christmas or Easter, out at the lake at a picnic, there was a long take just watching people doing things. When you’re revisiting that memory, when you put it in the VCR, you’re just like I get it, Dad. I see these people.

And then you get the rando who comes up in front of the camera and tries to show off. One of the things that always got me in old home movies was the people who wanted to come in and show their muscles. That was always the thing. I’m just like, how many times are people going to come up and flex at the camera? I love that. So exploring how to shoot that way, how to shoot sort of poorly and make it feel really fun for the story, I think was a really fun exploration and a challenge.

Guerrero: We shot on a VHS camera as well, and it’s so light that it feels like you’re playing with a toy camera. And we didn’t have the luxury of doing playback, because that damages the tape. We learned that on our first tape! So we would just shoot it like a VHS, probably just like [Nelson’s] Pops. He never went back and looked at what he’d shot on the player, he’d wait and watch it with everybody else. And we had to do the same. So it was just kind of All right, let’s just do three takes for everything.

Was everybody using retro technology, as opposed to shooting it with modern cameras and then converting it?

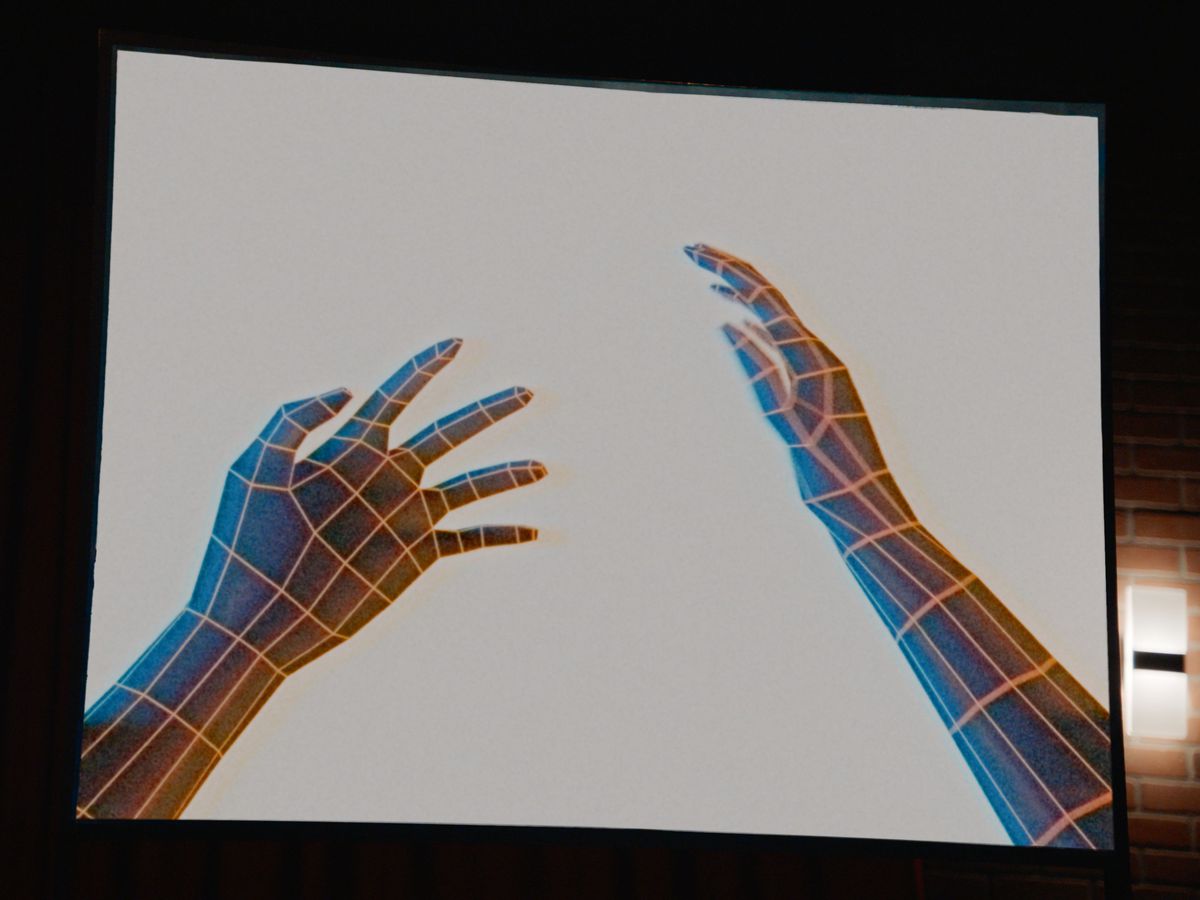

Kermani: We had a blend, because our piece has a lot of visual effects. This was an interesting piece, because it was so retro in so many ways, but then we were constructing an entire world digitally, so it’s a strange match in your brain. We wanted the environment to feel like Tron, but we wanted the monster to feel timeless. So the technique and the look of the monster is actually ahead of 1985 technology. Those visuals didn’t exist — they couldn’t actually animate like that.

We layered her a bunch of times, so there’s the Tron backdrop, and then in a separate layer, we ran our monster through a VHS process, ran it through tape a bunch of times, composited it back into the Tron backdrop. We were really messing around with like, OK, now we’ve gone too far, now you actually can’t see her at all. So it was a lot of experimenting, a lot of running through tape decks. I think our first version of her was taped over a copy of The Phantom Menace. So it was a lot of analog processes matched with digital processes.

Nelson: This is gonna sound ridiculous, but we shot ours on a Red [digital camera], knowing full well that we were going to really mess with the footage. I told Nick Junkersfeld, our DP, “I know we’re shooting on this crazy high-def camera, but just make sure we have the resolution where you can just go nuts with it.”

We did have an Omnimovie [VHS camcorder] with us at all times — we took an Omnimovie and a Red, and tried to find a lens that matched the Omnimovie in terms of zooms and optically. We went to this place in Minneapolis and tried out lenses until we said OK, yep, that’s it. Then I was like, “Nick, here’s some old VHS clips from my dad. Here’s some stuff I found on YouTube, because people also post their old VHS family videos on YouTube. This is what I want. We’re going to make this feel like a VHS home movie.”

David, you talked at the Q&A about shooting your short on a 40-year-old Magnavox camera that was literally disintegrating during production. How did that affect your shoot?

Bruckner: We had a few backups, but it was just a totally different way of thinking when the camera — the tubes were dying in the camera. We tested it and it looked great, but once we started running down hallways with it, it was getting damaged in tiny ways. We’d go to the monitor and look at footage, and these bizarre scan lines would start to appear. The image was just breaking down right in front of us.

To take it back to the fuck-you of it all, it’s liberating, going, Let’s just keep shooting. Let’s get as much out of it as we possibly can, until the camera completely craps out. It’s a totally different way of thinking, because we couldn’t control what was happening in the frame as much as we’re used to. It was fun.

V/H/S/85 is now streaming on Shudder.

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- PlatoHealth. Biotech and Clinical Trials Intelligence. Access Here.

- Source: https://www.polygon.com/23906539/vhs-85-director-interview-horror-anthology-shudder

- :has

- :is

- :not

- :where

- ][p

- $UP

- 1985

- 2021

- 2022

- 2023

- 8

- 90

- a

- Able

- About

- absolutely

- actors

- acts

- actual

- actually

- affect

- afraid

- After

- against

- ahead

- aircraft

- All

- along

- also

- always

- an

- and

- Animate

- anything

- Apartment

- appear

- ARE

- around

- AS

- ask

- asking

- At

- attempt

- attention

- audience

- audiences

- back

- backdrop

- backups

- battery

- BE

- beautiful

- Beauty

- became

- because

- been

- behind

- being

- Big

- Bit

- Black

- Blend

- Block

- blood

- both

- Brain

- Breaking

- Bunch

- but

- by

- camera

- cameras

- CAN

- Capturing

- Career

- carry

- certain

- challenge

- charged

- Christmas

- clarity

- clips

- collection

- come

- comes

- commercial

- completely

- concrete

- connected

- Connecting

- constructing

- construction

- consumer

- control

- converting

- Cool

- craft

- crazy

- Dad

- Dark

- David

- Death

- decade

- definitely

- Demand

- detail

- DID

- different

- digital

- digitally

- Director

- Directors

- discovered

- do

- doing

- Dont

- down

- Drops

- during

- Dying

- effects

- else

- embracing

- enormous

- Entire

- Environment

- Era

- especially

- etc

- Ether (ETH)

- Even

- eventually

- Every

- everybody

- everyone

- everything

- excited

- exist

- expectation

- exploration

- explore

- Exploring

- Failure

- family

- fans

- fantastic

- far

- fear

- Feature

- Features

- feel

- fest

- few

- Film

- films

- final

- Find

- First

- five

- For

- format

- found

- FRAME

- Franchise

- from

- front

- full

- fun

- funding

- get

- getting

- giant

- given

- gives

- Go

- going

- gone

- got

- grab

- great

- Green

- grew

- Ground

- had

- hand

- Hands

- happen

- Happening

- happens

- Hard

- Have

- he

- heavy-duty

- helped

- her

- here

- higher

- Hits

- hold

- holding

- holds

- Home

- horror

- hour

- How

- How To

- HTTPS

- Hunting

- i

- idea

- if

- image

- images

- impressive

- in

- inspired

- inspiring

- installment

- instant

- integrated

- interesting

- into

- IT

- ITS

- Job

- joined

- jpg

- just

- Keep

- kept

- keywords

- Kills

- Kind

- Know

- Knowing

- lab

- lake

- language

- latest

- layer

- layered

- learned

- Leave

- Lens

- lenses

- letting

- light

- like

- lines

- lineup

- little

- Long

- Look

- looked

- LOOKS

- Lot

- love

- loved

- Luxury

- made

- major

- make

- Making

- man

- many

- master

- Match

- matched

- May..

- maybe

- me

- mean

- means

- medium

- Memory

- message

- mike

- mind

- minutes

- Modern

- Moments

- Monitor

- more

- movie

- Movies

- much

- my

- Natural

- necessary

- never

- New

- next

- nick

- night

- no

- normal

- normally

- now

- observation

- of

- off

- often

- Old

- on

- once

- ONE

- only

- Opportunity

- opposed

- opposite

- or

- Orange

- original

- Originals

- Other

- Others

- our

- out

- over

- part

- particular

- People

- perfect

- Personally

- phantom

- phones

- piece

- Place

- plato

- Plato Data Intelligence

- PlatoData

- player

- playing

- Point

- Point of View

- Polygon

- Pops

- portrait

- possibly

- Post

- Premiere

- Prior

- probably

- process

- processes

- producer

- Production

- project

- projects

- proving

- Push

- put

- Q&A

- Questions

- really

- reasons

- Red

- regular

- Resolution

- Retro

- right

- Room

- ruin

- running

- Said

- same

- saw

- scan

- scene

- scope

- scott

- Screen

- secure

- see

- seemed

- seen

- segment

- segments

- sell

- sentiment

- separate

- Series

- setup

- she

- Shoot

- shooting

- Short

- shot

- shots

- should

- show

- showing

- Simple

- since

- single

- So

- some

- Someone

- something

- Sound

- split

- Star

- start

- started

- State

- steering

- Stir

- Story

- strange

- streaming

- structured

- studio

- such

- Super

- sure

- Swing

- Systems

- Take

- takes

- Talk

- tape

- technique

- Technology

- telling

- terms

- tested

- than

- that

- The

- their

- Them

- Themed

- then

- There.

- These

- they

- thing

- things

- think

- Thinking

- this

- those

- thought

- three

- Through

- time

- timeless

- times

- to

- today

- told

- too

- took

- Total

- TOTALLY

- toy

- tried

- Trucking

- trying

- tunnel

- two

- until

- Uphold

- us

- use

- used

- using

- version

- very

- Videos

- View

- viral

- visually

- visuals

- VOICES

- wait

- Wall

- want

- wanted

- was

- Watch

- watching

- Way..

- ways

- we

- webp

- WELL

- went

- were

- What

- What is

- whatever

- when

- whether

- which

- white

- WHO

- why

- will

- window

- with

- without

- woman

- Work

- worker

- working

- world

- would

- yes

- you

- young

- Your

- yourself

- youtube

- zephyrnet