Please enjoy!

Listen to the episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Overcast, iHeart, PlayerFM, Podchaser, Boomplay, Tune-In, Podbean, Google Podcasts, Amazon Music, or on your favorite podcast platform.

The show notes for this episode can be found here.

[0:03] Brady Walker: All right, welcome back to Pixels and Paint. We’ve got a special bonus episode with David Ariew. David, I only recently learned how to pronounce your name. I owe you an apology.

[0:17] David Ariew: Oh, no worries. People never know how to pronounce my name. There’s something weird because it’s a ‘W’ but pronounced like a ‘V’. It’s strange, like this one time a telemarketer called and got it right. I was just like, who are you? How do you know? It’s that kind of thing. So, yeah, totally.

[0:36] BW: It doesn’t seem like a very Polish looking name, so, yeah. For everyone who doesn’t know you or knows you as David Ariew, could you introduce yourself?

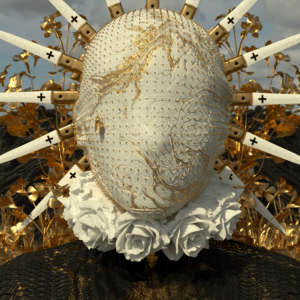

[0:56] DA: Sure. I’m a 3D artist and have been for over 12 years, covering a wide range of jobs in production and post-production — from shooting to editing, color grading, VFX, 2D and 3D motion design, to DIT. I’ve always gravitated towards 3D, which is my passion. My main background is in concert visuals; I started with Dave Matthews Band in 2011 and worked for artists like Katy Perry, Zedd, Lil Nas X, Excision, Keith Urban, Drake, and deadmau5. I’ve also collaborated extensively with Beeple, curating reels for his Ctrl Z events and working on Zedd visuals and FITC titles. Not widely known, but I created two of the Beeple and Madonna NFTs with him directing, which ranks as one of my weirdest jobs.

In March, I exhibited my work at his grand opening, an immersive experience that was new for me, having seen my work primarily on stages at concerts. Besides my production work, I’m also an educator in the 3D community. I earned the nickname Octane Jesus from a comment on one of my tutorials; I use Octane, a third-party GPU render engine, and teach it to others. It caught on after someone commented, and the name stuck.

The 3D motion community is fantastic; we share information, unlike some more cutthroat art communities. With 3D being so technical, it’s common to search for tutorials to fill gaps in knowledge. My head’s like a tutorial database rather than holding all the information itself. Education is a vital part of my career.

Additionally, I was one of the artists on Pak’s first $ASH drop and have sold my work through Nifty Gateway, SuperRare, and MakersPlace. I’ve just returned from the Digital Art Fair in Asia, in Hong Kong, and was part of the Sotheby’s contemporary evening auction alongside Banksy, Basquiat, Damien Hirst, and Jeff Koons — a mind-blowing experience made possible by a collector, Triple X, and famous Chinese painter Gi Lee, who I helped animate paintings for 3D.

My work spans various artistic styles, from cinematic, focusing on lighting, camera movement, and storytelling, to tightly synced visuals for concerts. Lately, thanks to NFTs, I’ve been exploring abstract, meditative pieces with 3D Infinite mirror rooms — a style unique to me. This new direction has led to creating immersive experiences, like the VR experience and the immersion room in Hong Kong, which elicit deep emotional responses, something quite rare in art.

[7:12] BW: There’s a lot to dig into there. It’s interesting, just as a sidebar, to piggyback on something you said—I remember in January, starting to play around with Midjourney and trying to figure things out. I was asking people on Twitter, “How’d you do this? How’d you do that?” And I was getting shut down left and right. Nobody wanted to trade their secrets, which is different from the 3D world. I agree, it’s probably because 3D is so technical and difficult that even if you tell someone how to do it, there’s still nuance there.

[8:02] DA: Totally. I can share as many techniques as I want, but I don’t expect people to reach the level I’m at, or they’ll make something uniquely their own. That’s what I aim for with my tutorials—I provide a base for people to build off of. For example, with a cyberpunk city, I show how to do everything but say, “Here are your building blocks, go make your own thing.” Or with my nature tutorials, I showed how to make it all look pretty and realistic, but I didn’t put in every little detail because that would’ve taken forever.

People took those and made their own art, which I think is a better way to do it. But I’m surprised with the Midjourney stuff; it’s technical, not like stable diffusion and all the techniques you can combine. Perhaps it’s like a gold rush, like NFTs, and people are hoarding their trade secrets, whatever weird things they’ve discovered, thinking it’ll make them millions. I hate that attitude. It sucks to hear.

[9:18] BW: In another podcast interview, you mentioned working on finding your own style, which was about two or three years ago. I revisited that interview recently for research. Your early mirror boxes trace back to around that time. Could you walk me through the process of finding your own style? It’s fascinating to approach this as a highly trained technical specialist, almost like a hired gun, then faced with the opportunity to be an artist. What were the trial and error points? What was going through your head?

[10:58] DA: Before NFTs, there was this hired gun aspect. My first mirror room was for the Latin Grammys, by this company called Possible. They wanted an infinite mirror room in 3D. I created a box and found that bevels that caught the light made it feel like a physical room. I put a chandelier in, and it reflected into infinity, thanks to Octane. Instead of stopping there, which they were happy with, I made a tutorial on creating infinite mirror rooms with different camera settings and warping. It was well-received.

Someone from the Republic of Georgia contacted me for pre-visualizations of mirror room installations in Hong Kong. I did that, and it led to Keith Urban’s team reaching out to me. They saw potential in the techniques I used. On the first day with them, I created 100 style frames instead of the usual 3 to 10, showing me the fruitfulness of these techniques.

With NFTs, I reached for these techniques again to create animations quickly for drops. I shared past short films initially, like a space-themed music video, which sold for a significant amount. But my new work was mostly this mirror room style, starting with concrete box shapes and evolving into more psychedelic forms with panoramic cameras and stretching effects. It resulted in complex and unpredictable visuals that were very freeing compared to the slow process of typical 3D art.

I’ve since focused on making more meditative visuals, like the 11-minute visual meditation for MakersPlace. Jeff from Ireland, who found me through Nifty Gateway, proposed using my art for guided visual meditations, leading to the creation of a slowed-down piece that worked really well for meditation.

Finding my own spirituality and connecting with people has been part of this journey. Bringing the art into VR adds a whole dimension that feels like drifting into the next life. It’s a powerful experience.

[21:11] BW: Yeah, the reactions in Hong Kong at Digital Art Fair Asia were impressive, especially in the immersive room where Refik Annadel had previously exhibited. I’m forgetting who the artist was last year.

[21:35] DA: Thank you.

[21:36] BW: And this year, it was you. I heard there were some powerful reactions, lots of repeat visits. What was your experience?

[21:46] DA: It was amazing. The first person we took into the VR experience was this guy named Howard, who was helping us set up. It was late, we were working on getting the files loaded, and I invited him to try the VR. He thought he’d stay for just a minute, but like everyone else, he was in there for much longer. When he came out, his whole demeanor had changed; he was serious, uplifted, and emotional. He told me the experience was powerful and to be careful with this technology. That reaction from my art was unexpected.

Some people came out crying. Chelsea [Evenstar, Ariew’s wife] told me about one girl who thought she heard voices in the experience that made her remember her past. She was so overwhelmed she needed to sit down. Others looked hopeful, relaxed. A collector tried it and told me it was the best experience of his life, which was surprising because I see the technical issues—it’s low-res, the frame rate is slow, and it’s compressed. But it’s like I’ve glimpsed into another dimension. It’s murky, but I know what it’s going to be when it’s fully realized.

People brought back their families and friends to try the VR. It was the highlight of the show, and I’ve never felt so appreciated as an artist. MakersPlace did an incredible job presenting digital art, and they’re positioning themselves as the leading platform for fine digital art. This collaboration and the opportunities from this event are exciting.

Potential Chapter Headings:

[24:54] BW: That’s beautiful. What I’m curious to know, because you’ve only been doing these light boxes for about three years, is whether you have a long-term vision. Are there things that you haven’t accomplished yet with it that you’re thinking, “This is what I’m going to do next,” or variations you have in mind?

[25:23] DA: Yeah, every time I dive into this world, I’ve thought I would tap it out. Yet, I always find new techniques and ideas, or I’ll stumble on something new and unique by changing some parameters. It’s about getting them to bigger canvases. A huge goal of mine is to get on the sphere in Vegas, the giant sphere. I did a job for it—a Coke pour for Coca-Cola, which is cool and got me the template for the sphere. I piped my art through, and it looks incredible.

I took the VR experience, which is just a 360 render, and piped it through the sphere, which works similarly as it’s inverted from the inside to the outside. I shared that on Twitter, and it got a lot of love. But people aren’t making the connection, because it looks like a template with four different camera angles.

So, I’m going to create an even more epic previsualization of what my art would look like on the sphere. I’ll create a fully 3D Vegas and have the sphere play in that environment. This is about creating experiences and upgrading the work I’ve developed over the past two to three years, like putting it on the sphere or in an immersive room. I’ve found new techniques, like making an immersive room seamless. But it’s not like I’m creating new art.

Up until recently, all my art was abstract because I wanted it to be an experience of infinity without concrete objects. However, over the past year and a half, I’ve become more spiritual, having guided meditation sessions with someone named Ali, which Chelsea found through NFTs. These sessions have helped me feel more connected to the universe and clear out life’s problems. I used to be skeptical about spirituality, but now I’ve become open-minded. It’s about trying things to see if they work for you.

After nearly a year, Ali started to give me free sessions and wanted to make art with me. Despite her not being a traditional artist or technically inclined, she insisted. When a project came up through MakersPlace, she flew out from England and we co-created. We animated a specific yew tree from near her house, used a skeleton key as inspiration for one scene, and incorporated a geometric star from my wife’s artwork. It was a new way of channeling creative energy. In the week she was here, we designed seven scenes, which was faster than my usual pace. I was working on client projects but still managed to create with her for two hours a day.

The future for me is designing for bigger experiences and bringing in more ancient spiritual symbolism into my realm. I want to focus on experiences over just 2D art pieces. The constraints help me dig further down into something amazing.

[34:03] BW: It’s interesting. I’ve wondered for a long time about the split between intuitive and conceptual writing, one being more technical. And in digital art, especially 3D, I’m curious about the trade-off. Often I see art that seems purely technical, lacking an intuitive phase. It sounds like your teacher became a proxy for your intuitive side, guiding you there.

[35:10] DA: Exactly. It takes years for a 3D artist to move past the technical to feel truly creative. This is the most creative I’ve felt, and she was like a teacher who unlocked my ability to think outside the box. Instead of focusing on the technical, I learned to focus on the desired feeling, to be experimental. The technical aspects are secondary, tackled later to refine the final look.

[35:50] BW: Is there a pen and paper component to your practice for intuitive work?

[35:56] DA: Not exactly. I’d probably draw if I were good at it. I’ve always intended to get into drawing and painting, but I’m just not skilled there. Normally, you’d find references, create mood boards, do style frames, animation tests, etc. But for this, there’s none of that. I don’t want it to interfere. I prefer to dive directly into the software and create within that space because planning isn’t feasible for me. I can’t envision what a diamond-shaped mirror box will look like until I see it in the software, so I create in the moment, in partnership with the software.

[36:48] BW: You mentioned your more tangible, subject-oriented work. I find Forest Lanterns to be my favorite piece because it beautifully merges abstraction and figuration. Could you talk about your process? Do you start with a visual, narrative, or emotive idea, or is it a blend?

[38:04] DA: That’s a reasonable question for someone with a more defined process. “Forest Lanterns” began as visuals for a Dave Matthews Band concert. I was experimenting, and a lot of those visuals didn’t make the final cut, so I used them elsewhere. It often starts with exploring techniques, like creating nature scenes and thinking about what could enhance them. My wife is a great source of ideas, too.

Over 12 years, I’ve grown comfortable with blank slates, often getting vague briefs from indie clients who ask for ‘the David style.’ I don’t storyboard much; I prefer to jump into the software. That’s where I’m most comfortable, blocking out compositions and tweaking lighting and colors. I work on everything simultaneously, adjusting elements until it feels right.

The same goes for my mirror room pieces; it’s about experimenting in the software rather than extensive pre-planning. I’ll do animation tests for functionality, but I’ll also do overnight renders, letting my computer work while I sleep. Sometimes those renders turn out to be final. It’s a bit of a rambling answer, but that’s how it works for me.

[40:32] BW: You started as a filmmaker, right? Did you study filmmaking in college?

[40:43] DA: No, I studied neuroscience in college and got a master’s in it. I was on a path set by my academic parents; my dad’s a philosophy professor. The concept of an artist to them equated to starving artist. My wife encouraged me to pursue filmmaking when we were together in 2011.

[40:49] BW: Ah, that’s right, you even started grad school in neuroscience.

[40:54] DA: Yeah, I did. I’ve always been a tech enthusiast, starting with a GoPro, then moving on to a 5D, lights, a jib, trying out a Steadicam. But I was never a great cinematographer. It was just enough to teach me the basics, like communicating with a DP on set, especially for VFX work. I’ve done stints in Steadicam, editing, and color grading, but most of my expertise is in post-production. I wouldn’t call myself an expert in shooting or cinematography, rather in digital cinematography where I can craft the perfect camera move without the physical hassles.

[42:49] BW: You’ve mentioned in previous interviews a goal to create longer short films and possibly sell them as NFTs. Is that still part of your plan?

[43:07] DA: It’s more of a maybe now. I’d love to finish my cyberpunk film. It’s a fantastic learning opportunity. If I had no client work and could go all-in on web3, I’d split my time between my main projects and occasionally do something to push my boundaries and learn new techniques. These can be really valuable, like when I recently needed realistic water motion for a scene. I used a friend’s raindrop shader in Houdini, which was perfect.

But ideally, I’d learn Houdini myself to create more complex effects since Cinema 4D sometimes falls short. For instance, animated bevels on my pieces can cause flickers in the geometry or reflections, so I’m having to work around those issues. Mastering a more advanced software would enhance my current direction, but I’m focusing on my current style because of the strong response it gets and because it’s what I love to do as an artist.

[45:16] BW: I’m curious about your philosopher father’s reaction to your lightboxes and mirror boxes.

[45:26] DA: I haven’t spoken to him since I returned. I’ve talked to my mom, but I’m also curious about his reaction. We might not delve deep, though, because our philosophies differ significantly now. He’s quite judgmental about this kind of stuff, creating somewhat of a barrier within my family.

[45:54] BW: What’s his philosophy background?

[46:01] DA: He’s more of a historian of philosophy. Actually, he’s one of the world’s foremost experts on Descartes. He isn’t just an armchair philosopher; he’s fully immersed in the context of Descartes’ life, having extensively studied all of Descartes’ correspondences and the historical backdrop to understand him better.

[46:44] BW: You’ve mentioned that a lot of your strong convictions stem from your upbringing. I imagine that had a significant impact on you.

[47:01] DA: Absolutely, we’re all deeply influenced by our parents, not just by what they say, but also by observing their behaviors. Eventually, we define ourselves and how we’re different from them. I was somewhat of a late bloomer; I used to hold my parents in such high regard, seeing them as authority figures and thinking they were always right. But now, I’ve shifted to trust my own judgment.

The past few years have seen a major shift in my consciousness, and NFTs played a part in that. They opened my eyes to the idea that money isn’t necessarily real and that anything can happen if we create it. And when the bear market hit, after working non-stop for 12-13 years, I decided to take a break. I realized that my priorities are my wife, my family, and becoming a more well-rounded person, not just an artist.

I’ve met many artists who can’t define their hobbies outside of their art. They pour their whole selves into their work, but I don’t think that’s healthy. To be an artist, you need to be well-rounded and have something to say. For years, I struggled with not knowing what art to create because I didn’t feel like I had anything to say, but that’s starting to change.

[49:04] BW: It’s fascinating to see how your journey is reflected in your art. Shifting gears, among the many technical skills you’ve acquired, which piece of art theory or understanding do you find most valuable for any artist?

[49:46] DA: That’s tricky. I’d say soft skills are more important than technical skills. Technical skills involve knowing how to simulate water or operate software, but soft skills, which come from years of experience, include camera movements, lighting, composition, storytelling, editing, color theory, and motion design. Mastering these can take years, but they’re crucial to creating something beautiful.

For me, understanding motion and smooth transitions in motion design is essential. But lately, I’ve been drawn to the beauty of unexpected results, like tweaking simple parameters to achieve intricate movements. Throughout my career, I’ve sought shortcuts to achieve complexity without exhaustive effort. Discovering something like infinite mirror rooms, where the interplay of light and reflections creates complexity effortlessly, is what I aim for. It allows me to play and have fun instead of agonizing over every detail.

However, there’s a contrast with AI art—it’s almost too easy, and it’s challenging to distinguish oneself with something so accessible. I’m drawn to difficult tasks, like pinball. I’ve become a pinball enthusiast; the challenge is rewarding. Similarly, I strive to outpace AI by mastering skills it hasn’t yet replicated.

[53:18] BW: Storytelling—how do you imbue your abstract pieces with a story or story-like feeling?

[53:26] DA: That’s a good question. It often depends on the music and whether the song or visuals come first. Sometimes I animate to a track from Premium Beat, shaping the visuals to align with the audio. Other times, I create a visual narrative without sound or with a temporary track, but recently, it’s often with no sound at all. I let the visuals dictate the transitions to the next scene.

Then my composer, a sound wizard, scores it, usually hitting the mark with little guidance from me. This collaboration, which was rekindled through NFTs after we had drifted apart, has become a pivotal part of our creative process.

Regarding the narrative arc, especially in the nine-minute immersion room, it’s less about concrete planning and more about intuition. I rely on feeling and key transition points to weave the story. For instance, I’ll spot moments where different elements naturally connect—like transitioning through a tree into another scene, or a light orb merging into a galaxy. These become ‘hero moments’ around which I construct the rest.

In the particular piece I’m referring to, the galactic burst is the climax, shifting the perspective from internal scenes to a view of outer space, before winding down to the resolution. The piece begins with pure abstraction, inviting viewers to find their footing before introducing more tangible spiritual symbols, like the tree. The abstract then serves as a transitional dimension, leading back to grounded elements like the lotus, the cave, and finally the galactic scene.

While some creators may plan meticulously, I prefer a more fluid process, refining the piece until it just feels right.

[56:53] BW: It makes a lot of sense. Your work feels very musical, and I see storytelling in two ways: the traditional method like sitting around a fire, and then there’s the more musical, impressionistic style. Your work definitely fits in that impressionistic camp.

[57:25] DA: I definitely agree with that.

[57:28] BW: I’m curious, you did well in Hong Kong, but how has the bear market treated you? How have you been faring?

[57:39] DA: It was really hard. To me, the last big moment was in February when Ness Graphics, a buddy of mine, released his open edition and it blew up, making 2 million. For a second, the spotlight swung back to digital artists. We helped kick off the NFT trend, but then it felt like we were in a smaller bubble compared to the PFP craze. And I participated in that too, getting involved in the buying and selling frenzy. It was fun but different from digital art.

It’s exciting that digital art is establishing itself as a revolution where it’s not just about NFTs but about digital art itself. The digital art fair will hopefully draw people from the traditional art world who are tired of its elitism and stuffy vibes. These big collectors, they’re like renegades looking for something new.

So, I’ve talked to many of these collectors, especially in Hong Kong. It’s such a hub for pushing technology, and it makes sense they’d be early adopters of digital art, using cryptocurrencies. A lot of these people are starting to find the traditional art world boring. One collector, who had been in traditional art for over 20 years with a massive collection, found NFTs refreshing. As a sci-fi nerd interested in technology, she represents the Renegades seeking to break from the elitist world and connect with artists directly.

In the traditional art world, artists don’t really interact with their collectors; there’s this invisible wall. But in the web3 space, collectors become your best friends, advocates, and part of a fan club that supports your art, which is amazing. What was your question again?

[1:00:56] BW: How have you been faring?

[1:00:58] DA: In February, I did an open edition and sold 715 pieces, which was $40,000—huge for the bear market. I then evolved the collection with a series of burns. I used pox language, where a 15-second piece could be combined to make a 30-second piece, and so on, leading to collaborations, like one featuring the Mona Lisa stepping out of her frame and another with mythical creatures mesmerized by my digital art in a reflection pool. Despite the success, I lost momentum and had to take on client work due to financial losses.

Throughout 2022, I worked on a project called Diamond Don, which aimed to bring transparency to diamond certification using blockchain. We had 300 diamonds and a 10-pound box that transformed into a pedestal for the diamond. Despite the great idea, it failed due to the bear market; we sold only 20 diamonds. We attempted to market it privately, with an invitation-only approach, but the high price didn’t suit the market conditions.

I sold off valuable NFTs to stay in web3, but eventually, I had to pivot back to client work after my business partner ghosted me. This year, my Hong Kong trip has revitalized my hope in web3, allowing me to focus on my art, unlike previous collaborations that felt more like well-paid client work but lacked personal artistic fulfillment.

[1:06:06] BW: It’s great to see how your unique vision is blossoming. As an OG in the NFT world, what needs to happen in the digital art realm for it to evolve and succeed?

[1:06:40] DA: Yeah, the gamifying of our art and the blockchain aspects are great, but they appeal to a small percentage of people. With the MakersPlace drop, we thought about burns, but we decided against it to reduce friction for new adopters. MakersPlace has credit card payments, which is fantastic.

For instance, a collector of mine in Hong Kong, Angela, introduced her friend Simone to digital art. Simone has been a traditional art collector and didn’t understand NFTs at first. She even asked if buying VR meant the painting would arrive first. I had to steer her away from VR to an open edition piece, which is simpler. The first step is getting the traditional art market to take digital art seriously through in-person events and experiences. Then, explaining how the blockchain creates scarcity is essential—like a network of computers verifying transactions on an immutable spreadsheet.

We’re all trying to reach mass adoption by presenting digital art in ways that have real-world utility. Whether it’s attending events, connecting with the community, or showing that owning a digital piece can be fun and valuable, we’ll spread and expand gradually.

We’re in a slow growth phase after the Bull Run, but another catalyst will come. I’m excited about the Apple Vision Pro, which might change how we approach computing. We’re evolving the technology, aiming for a Metaverse where digital items have a place—attached to your avatar or woven into your clothing. These technologies will converge, and hopefully, that’s when we’ll all hurt a little less in this space.

[1:10:43] BW: What do you think is the role of physicals in Web3?

[1:10:49] DA: I think it was a hot point of contention for a while. A lot of people were anti-physical, but I find that to be a closed-minded view. I’ve always been a digital artist and I don’t know how to create a good physical. But that’s where collaboration comes in. It’s great to partner with artists who excel in physicals. For instance, I’d love to work with someone who can incorporate physical mirror box sculptures with screens or LEDs displaying my digital art. It adds another dimension, like having my digital mirror box art interact with actual mirrors.

Imagine an installation exhibition with mirrored floors and ceilings or a corridor leading to a full immersion room decked out with VR headsets adorned with mirrors. Physicals open up a whole new avenue. People’s success exemplifies this. He invested his earnings into a studio that’s now an incredible art experience venue, showcasing digital art on walls and the ‘Human One’ box. It’s a smart move and sets you apart as an artist. So, I have no issues with physicals; I think they’re important.

[1:12:31] BW: With your work in particular, I would love to see a mirror box that resembles the large scale sculptures of Donald Judd. His work imposes on physical space and often features big blocks that protrude from the wall or stand in the middle of a room. I’m curious to see how you could take that idea and apply it to a mirror box.

[1:13:17] DA: Donald Judd, right? I’ll definitely look into that.

[1:13:20] BW: Yeah, he’s the artist who transformed Marfa into an art town.

[1:13:29] BW: He bought a bunch of old army barracks in Marfa, Texas, and transformed them into his art studio, eventually installing his friends’ work there. It’s blossomed into an artsy little destination, mostly for New Yorkers, but it has since gained broader popularity.

[1:13:53] DA: People crave these experiences, often without realizing it. Meow Wolf, for example, is super popular, and there’s TeamLab. We’re trying to create the future of art, which doesn’t always have to be confined to a computer screen. Let’s make it big, impressive, and impactful, showing what it can do beyond traditional art. It’s all art at the end of the day.

[1:14:24] BW: Brian Eno, who’s a personal Lord and Savior of mine, discusses the difference between working within a form and working on a form, by which he means reimagining the form itself. So when you see a book that’s perhaps boxed and composed of different parts, the artist has not only worked within a medium but has reimagined the form of a book itself. It’s about transforming art from creating a painting to reimagining what a painting can be, incorporating elements from sculpture and animation. That’s when I become really excited.

[1:15:27] DA: Exactly. There’s total freedom to use any medium you want; the only limit is technical knowledge. That’s where collaboration is invaluable because you can create something that’s larger than yourself and spans multiple mediums.

[1:15:48] BW: And speaking of Brian Eno, I’ve adopted my final question for interviews from him. It’s about why humans create art. Every human civilization has decorated their tools or surroundings at the very least. So, I ask, why do humans create art? Does it have a use?

[1:16:37] DA: That’s an interesting question. Everything we design is art, including the architecture around us. For me, creating art is incredibly satisfying. It feels like creating another dimension, a place I want to visit. Jules Urbach, the CEO of Otoy, is working towards creating a holodeck-like experience. I’ve seen a prototype of a 3D TV by Looking Glass Factory that offers a multi-perspective view, almost like a hologram. Imagine a room lined with such TVs; it would be like stepping into another world.

For me, my art seems to be therapeutic, almost healing, whether it’s bringing people in touch with their mortality or providing a sense of relaxation. I see potential uses in hospitals, for instance. It’s not just art; it’s an invention, combining art and technology. Artists may have one of the most important jobs—connecting with people’s emotions, bringing them together, making them think, healing them. My wife attended a traditional art conference where it was said that the job of artists is to bring heaven to earth.

We are increasingly at odds with each other, becoming isolated rather than forming communities, partly due to the internet and our immersion into digital lives. My goal is to bring spirituality and connection to the digital realm, creating beauty and order out of chaos.

[1:20:51] BW: That’s beautifully put. I wish I could have seen the immersive room in Hong Kong in its full glory.

[1:21:01] DA: There’ll be more iterations. I’ve been talking to a guy in Dubai; I can’t reveal details, but he has this cylindrical immersion room with a curved screen that wraps around you. I provided him the file, and it looks incredible with the reflective floor and ceiling, fog elements, and surround sound. I’m going to try to bring this to more places—that’s my mission.

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- PlatoHealth. Biotech and Clinical Trials Intelligence. Access Here.

- Source: https://rare.makersplace.com/2023/11/09/transcript-e22-david-ariew-meditative-mirror-boxes-with-octane-jesus/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=transcript-e22-david-ariew-meditative-mirror-boxes-with-octane-jesus

- :has

- :is

- :not

- :where

- $UP

- 01

- 06

- 07

- 1

- 10

- 100

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15%

- 16

- 17

- 20

- 20 years

- 2011

- 2022

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 27

- 28

- 29

- 2D

- 300

- 31

- 32

- 35%

- 36

- 360

- 39

- 3d

- 3D motion

- 3D world

- 40

- 46

- 49

- 50

- 51

- 53

- 54

- 58

- 7

- 8

- 9

- a

- ability

- About

- absolutely

- ABSTRACT

- abstraction

- academic

- accessible

- accomplished

- Achieve

- acquired

- actual

- actually

- Adds

- adjusting

- adopted

- adopters

- Adoption

- advanced

- advocates

- After

- again

- against

- ago

- AI

- aim

- aimed

- Aiming

- align

- All

- Allowing

- allows

- almost

- alongside

- also

- always

- amazing

- Amazon

- among

- amount

- an

- Ancient

- and

- Animate

- animation

- animations

- Another

- answer

- any

- anything

- apart

- appeal

- Apple

- Apply

- approach

- Arc

- architecture

- ARE

- Army

- around

- Art

- artist

- artistic

- Artists

- artwork

- AS

- asia

- ask

- asking

- aspect

- aspects

- At

- attempted

- attending

- attitude

- Auction

- audio

- authority

- avatar

- Avenue

- away

- back

- backdrop

- background

- BAND

- Banksy

- barrier

- base

- Basics

- BE

- Bear

- Bear Market

- beat

- beautiful

- beautifully

- Beauty

- became

- because

- become

- becoming

- been

- Beeple

- before

- began

- being

- besides

- BEST

- Better

- between

- Beyond

- Big

- bigger

- Bit

- blank

- Blend

- blockchain

- blocking

- Blocks

- blossoming

- Bonus

- book

- Boring

- bought

- boundaries

- Box

- boxes

- Break

- Brian

- bring

- Bringing

- broader

- brought

- bubble

- build

- Building

- bull

- Bull Run

- Bunch

- burns

- business

- but

- Buying

- by

- call

- called

- came

- camera

- cameras

- Camp

- CAN

- card

- card payments

- Career

- careful

- Catalyst

- caught

- Cause

- cave

- ceiling

- ceo

- Certification

- challenge

- challenging

- change

- changed

- changing

- Chaos

- Chapter

- chinese

- Cinema

- cinematic

- cinematography

- City

- clear

- client

- clients

- Clothing

- club

- coca-cola

- collaborated

- collaboration

- collaborations

- collection

- collector

- collectors

- College

- color

- combine

- combined

- combining

- come

- comes

- comfortable

- comment

- commented

- Common

- communicating

- Communities

- community

- company

- compared

- complex

- complexity

- component

- composed

- Composer

- composition

- computer

- computer screen

- computers

- computing

- concept

- conceptual

- concert

- concerts

- concrete

- conditions

- Conference

- Connect

- connected

- Connecting

- connection

- Consciousness

- constraints

- construct

- contemporary

- context

- contrast

- converge

- Cool

- corridor

- could

- covering

- craft

- crave

- create

- created

- creates

- Creating

- creation

- Creative

- creators

- creatures

- credit

- credit card

- crucial

- Crying

- cryptocurrencies

- curating

- curious

- Current

- Cut

- cyberpunk

- DA

- Damien Hirst

- Database

- Dave

- David

- day

- decided

- deep

- define

- defined

- definitely

- delve

- depends

- Design

- designed

- designing

- desired

- Despite

- destination

- detail

- details

- developed

- Diamond

- dictate

- DID

- differ

- difference

- different

- difficult

- Diffusion

- DIG

- digital

- Digital Art

- Dimension

- directing

- direction

- directly

- discovered

- discovering

- displaying

- distinguish

- DIT

- dive

- do

- does

- Doesn’t

- doing

- don

- donald

- done

- Dont

- down

- drake

- draw

- drawing

- drawn

- Drop

- Drops

- Dubai

- due

- each

- Early

- early adopters

- earned

- Earnings

- earth

- easy

- editing

- edition

- Editorial

- Education

- effects

- effort

- effortlessly

- elements

- else

- elsewhere

- emotions

- encouraged

- end

- energy

- Engine

- England

- enhance

- enough

- enthusiast

- Environment

- envision

- EPIC

- episode

- error

- especially

- essential

- establishing

- etc

- Even

- evening

- Event

- events

- eventually

- Every

- everyone

- everything

- evolve

- evolved

- evolving

- exactly

- example

- Excel

- excited

- exciting

- exemplifies

- exhibited

- exhibition

- Expand

- expect

- experience

- Experiences

- experimental

- expert

- expertise

- experts

- explaining

- Exploring

- extensive

- extensively

- Eyes

- faced

- factory

- Failed

- fair

- Falls

- families

- family

- famous

- fan

- fantastic

- fascinating

- faster

- Favorite

- feasible

- Features

- Featuring

- February

- feel

- felt

- few

- Figure

- Figures

- File

- Files

- fill

- Film

- filmmaking

- films

- final

- Finally

- financial

- Find

- finding

- fine

- finish

- Fire

- First

- Floor

- floors

- fluid

- Focus

- focused

- focusing

- Fog

- For

- foremost

- forever

- form

- forms

- found

- four

- FRAME

- Free

- Freedom

- frenzy

- friction

- friend

- friends

- from

- fulfillment

- full

- fully

- fun

- functionality

- further

- future

- gained

- Galaxy

- gaps

- gateway

- gears

- geometry

- Georgia

- get

- getting

- giant

- Girl

- Give

- glass

- glimpsed

- glory

- Go

- goal

- Goes

- going

- Gold

- good

- got

- GPU

- gradually

- grand

- graphics

- great

- grown

- Growth

- guidance

- guided

- Guy

- had

- Half

- happen

- happy

- Hard

- hate

- Have

- having

- he

- head

- headsets

- healing

- healthy

- hear

- heard

- help

- helped

- helping

- her

- here

- High

- Highlight

- highly

- him

- his

- historical

- Hit

- hitting

- hoarding

- Hobbies

- hold

- holding

- Hologram

- Hong

- Hong Kong

- hope

- hopeful

- Hopefully

- hospitals

- HOT

- HOURS

- House

- How

- How To

- howard

- However

- HTTPS

- Hub

- huge

- human

- Humans

- Hurt

- i

- I’LL

- idea

- ideally

- ideas

- if

- imagine

- immersed

- immersion

- immersive

- immutable

- Impact

- impactful

- important

- impressive

- in

- Inclined

- include

- Including

- incorporate

- Incorporated

- incorporating

- increasingly

- incredible

- incredibly

- Indie

- Infinity

- influenced

- information

- initially

- inside

- Inspiration

- installation

- installing

- instance

- instead

- intended

- interact

- interested

- interesting

- interfere

- internal

- Internet

- Interview

- Interviews

- into

- intricate

- introduce

- introduced

- introducing

- intuition

- intuitive

- invaluable

- Invention

- invested

- invisible

- invited

- inviting

- involve

- involved

- ireland

- isolated

- issues

- IT

- items

- iterations

- ITS

- itself

- January

- Job

- Jobs

- journey

- jump

- just

- Katy Perry

- keith

- Key

- kick

- Kind

- Know

- Knowing

- knowledge

- known

- knows

- Kong

- lacking

- language

- large

- larger

- Last

- Last Year

- Late

- later

- Latin

- leading

- LEARN

- learned

- learning

- least

- Led

- Lee

- left

- less

- let

- letting

- Level

- Life

- light

- Lighting

- like

- LIL

- LIMIT

- lined

- little

- Lives

- Long

- long time

- long-term

- longer

- Look

- look like

- looked

- looking

- LOOKS

- losses

- lost

- Lot

- lots

- love

- made

- Main

- major

- make

- MAKES

- Making

- managed

- many

- March

- mark

- Market

- market conditions

- Mass

- Mass Adoption

- massive

- master’s

- Mastering

- May..

- maybe

- me

- means

- meant

- Meditation

- medium

- mentioned

- merges

- merging

- met

- Metaverse

- method

- meticulously

- Middle

- MidJourney

- might

- million

- millions

- mind

- mine

- minute

- mirror

- Mission

- mom

- moment

- Moments

- Momentum

- money

- mood

- more

- mortality

- most

- mostly

- motion

- move

- movement

- movements

- moving

- much

- multiple

- Music

- musical

- my

- myself

- name

- Named

- NARRATIVE

- nas

- Nature

- Near

- nearly

- necessarily

- Need

- needed

- needs

- network

- Neuroscience

- never

- New

- next

- NFT

- NFTs

- Nifty

- Nifty Gateway

- no

- None

- normally

- Notes

- now

- Nuance

- objects

- Odds

- of

- off

- Offers

- often

- oh

- Old

- on

- ONE

- only

- open

- opened

- opening

- operate

- opportunities

- Opportunity

- or

- order

- Other

- Others

- our

- ourselves

- out

- outer space

- outside

- over

- overnight

- overwhelmed

- own

- owning

- Pace

- paint

- painter

- painting

- paintings

- Paper

- parameters

- parents

- part

- participated

- particular

- partner

- Partnership

- parts

- passion

- past

- path

- payments

- People

- people’s

- percentage

- perfect

- perhaps

- person

- personal

- perspective

- phase

- philosophies

- philosophy

- physical

- piece

- pieces

- Pivot

- pivotal

- Place

- plan

- planning

- platform

- plato

- Plato AiStream

- Plato Data Intelligence

- PlatoAiCast

- PlatoData

- Play

- played

- podcast

- Point

- points

- Polish

- pool

- Popular

- popularity

- positioning

- possible

- possibly

- post-production

- potential

- powerful

- practice

- prefer

- Premium

- pretty

- previous

- previously

- price

- primarily

- Pro

- probably

- problems

- process

- Production

- Professor

- project

- projects

- pronounced

- proposed

- prototype

- provide

- provided

- providing

- proxy

- purely

- pursue

- Push

- Pushing

- put

- Putting

- question

- quickly

- quite

- range

- ranks

- RARE

- Rate

- rather

- reach

- reached

- reaching

- reaction

- reactions

- real

- real world

- realistic

- realized

- realizing

- really

- realm

- reasonable

- recently

- reduce

- references

- refik

- refine

- refining

- reflected

- reflection

- Reflections

- regard

- reimagined

- reimagining

- relaxation

- relaxed

- released

- rely

- remember

- renders

- repeat

- replicated

- represents

- Republic

- research

- resembles

- Resolution

- response

- responses

- REST

- resulted

- Results

- reveal

- Revolution

- rewarding

- right

- Role

- Room

- Rooms

- Run

- rush

- Said

- same

- saw

- say

- Scale

- Scarcity

- scene

- scenes

- School

- sci-fi

- scores

- Screen

- screens

- seamless

- Search

- Second

- secondary

- secrets

- see

- seeing

- seeking

- seem

- seems

- seen

- sell

- Selling

- sense

- Series

- serious

- seriously

- serves

- sessions

- set

- Sets

- settings

- seven

- shapes

- shaping

- Share

- share information

- shared

- she

- shift

- shifted

- SHIFTING

- shooting

- Short

- show

- showcasing

- showed

- showing

- Shut down

- side

- significant

- significantly

- Similarly

- Simple

- simultaneously

- since

- sit

- Sitting

- skeptical

- skilled

- skills

- sleep

- slow

- small

- smaller

- smart

- smooth

- So

- Soft

- Software

- sold

- some

- Someone

- something

- sometimes

- somewhat

- song

- sought

- Sound

- Source

- Space

- spans

- speaking

- special

- specialist

- specific

- split

- spoken

- Spot

- Spotify

- Spotlight

- spread

- Spreadsheet

- stable

- stages

- stand

- Star

- start

- started

- Starting

- starts

- stay

- steer

- Stem

- Step

- stepping

- Still

- stopping

- Story

- storyboard

- storytelling

- strange

- strive

- strong

- studied

- studio

- Study

- style

- styles

- succeed

- success

- such

- Suit

- Super

- SuperRare

- Supports

- sure

- surprised

- surprising

- Take

- taken

- takes

- Talk

- talking

- tangible

- Tap

- tasks

- teacher

- team

- tech

- Technical

- technical skills

- technically

- techniques

- Technologies

- Technology

- tell

- template

- temporary

- tests

- texas

- than

- thank

- thanks

- that

- The

- The Basics

- The Future

- the information

- their

- Them

- themselves

- then

- theory

- Therapeutic

- There.

- These

- they

- thing

- things

- think

- Thinking

- third-party

- this

- this year

- those

- though?

- thought

- three

- Through

- throughout

- tightly

- time

- times

- tired

- titles

- to

- together

- told

- too

- took

- tools

- Total

- TOTALLY

- touch

- towards

- town

- trace

- track

- trade

- traditional

- trained

- Transactions

- Transcript

- transformed

- transforming

- transition

- transitioning

- transitions

- Transparency

- treated

- tree

- Trend

- trial

- trial and error

- tried

- trip

- Triple

- truly

- Trust

- try

- trying

- TURN

- tutorial

- tutorials

- tv

- tweaking

- two

- typical

- understand

- understanding

- Unexpected

- unique

- uniquely

- Universe

- unlike

- unpredictable

- until

- urban

- us

- use

- used

- uses

- using

- usual

- usually

- utility

- Valuable

- variations

- various

- VEGAS

- Venue

- verifying

- very

- Video

- View

- viewers

- vision

- Visit

- Visits

- visuals

- vital

- VOICES

- vr

- VR Experience

- VR headsets

- walk

- walker

- Wall

- want

- wanted

- was

- Water

- Way..

- ways

- we

- Weave

- Web3

- Web3 space

- week

- welcome

- WELL

- were

- What

- whatever

- when

- whether

- which

- while

- WHO

- whole

- why

- wide

- Wide range

- widely

- wife

- will

- with

- within

- without

- Wolf

- Work

- worked

- working

- works

- world

- world’s

- would

- woven

- writing

- X

- year

- years

- yet

- you

- Your

- yourself