Listen to the episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Overcast, iHeart, PlayerFM, Podchaser, Boomplay, Tune-In, Podbean, Google Podcasts, Amazon Music, or on your favorite podcast platform.

The Show Notes for this episode can be found here.

The article “Glitch Art: An Absolute Beginners Guide” inspired by this conversation, can be read here.

[0:05] Brady Walker: I’m super excited today to have Dawnia Darkstone on to the Pixels and Paint podcast. Dawnia, thank you for joining us.

[0:15] Dawnia Darkstone: Absolutely. Thanks for having me here, Brady.

Discovering Glitch Art and AI

[0:17] BW: Dawnia Darkstone, could you please introduce yourself to our listeners, both those who might not know you and those who do, but don’t know everything about you.

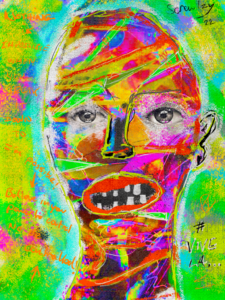

[0:31] DD: Certainly. I am Dawnia Darkstone, also known as “Let’s Get To It,” my online artist pseudonym from about 10 years ago. That’s around the same time I started making glitch art. Before that, for about five years, I was a photographer, mostly shooting local events and nature, and doing a lot of concert photography.

Then I was involved in a series of car accidents. I was just sitting at red lights, and got rear-ended both times. I lost the ability to do event photography, which is quite physically strenuous. I fell into a creative rut, not knowing how to express myself after losing what felt like my creative child.

Then I stumbled upon glitch art via a few tutorials by Benjamin Berg and Rosa Menkman’s work. I quickly fell in love with the whole practice, getting obsessed with finding new file formats to corrupt.

A few years later, Google Deep Dream was released, the first iteration of AI art. To me, it fit within the glitch art ethos. When it first came out, there wasn’t really a venue for AI art, so a lot of people creating that kind of work were posting in the Glitch Artists Collective, a group I helped administrate and co-curate on Facebook.

I’ve been incorporating AI into my work since then, especially given the acceleration of that technology in the last couple of years with new iterations like Mid-Journey, Stable Diffusion, Fusion, and Chat GPT.

I also do a lot of collage work, particularly in relation to AI. Collage and AI work fit together well. It’s nice being able to produce the exact elements you want for a piece without having to borrow directly copyrighted works from other artists.

Most recently, I co-curated the Glitch Beyond Binary show for Show the BS, where my work was also featured. I curated an NFT room for Super Cheap and had work featured in a glitch art show in South Korea, curated by Patrick Amadon.

Now, I’m preparing to offer a class via Palmdale, teaching sonification techniques. That involves editing images and video in a digital audio workspace as raw sound data. I’m excited to teach people about that.

Sonification

[4:30] BW: That’s very cool. I have many questions about what you’ve just said. To start, could you tell me a bit about the first glitch techniques you used? You’ve run the gamut from analog to digital, hardware corruption, and software corruption.

[5:02] DD: My first technique was sonification. As I said, Benjamin Berg had some tutorials available. This is when you take an image or a video and convert it into raw data, which is like an uncompressed TIFF or BMP file. Without the header data preceding the raw data, there’s no difference between it and a wall of audio file. You can import this into Audacity, Reaper, Ableton, or the like, and edit the images and videos as if they were sound.

I specialized in this technique for a while. I took things further by converting the images back into a wall format, and discovered that you can open that in any digital audio program, like Reaper. Then you can use VST plugins to affect the images or videos with envelopes, which change over time. If you tweak around, you can make something that sounds like music. That’s what got me featured in Vice magazine – making music out of image files. You can either view it as an animated video or open it as an actual sound file to listen to as music.

[7:03] BW: That’s really cool. I might want to jump into that class.

[7:10] DD: Yes, it’s fairly accessible. I know it might sound technical and complicated, but once you start, it’s quite straightforward.

[7:24] BW: Is audio still a part of your practice?

[7:30] DD: Definitely, though I wouldn’t say I specialize in it. I still incorporate audio into my works because sometimes a video file might be more appealing or have a better presentation with audio attached. I’ve been excited about Google’s new music AI program and am curious about where that technology is going. I’ve used it, mostly trying to break it and get it to output nonsense, but they have strong controls on it.

The Art of Breaking

[8:17] BW: So, it’s hard to break. On your objkt profile, you have the slogan, “I break things for a living.” Can you tell me more about that?

[8:31] DD: Certainly. It’s a playful, succinct way of describing glitch art. You’re basically breaking things, and sometimes the effect is aesthetically pleasing, though often it’s not. Glitch art involves a lot of curation. You may end up with thousands of variations of something you’ve broken, and you’re trying to find the one that speaks to you or is aesthetically pleasing.

I also literally break things when I’m doing circuit bending, another form of glitch art that I’ve practiced. I’ve mainly worked with these inexpensive digital cameras designed for kids, which are as good quality as point-and-shoot cameras from 10 or 20 years ago. You can open these up, poke around with soldering equipment on the circuitry, and create wild visual effects. With a bit of solder, you can stabilize these effects. This results in a circuit-bent, automatic glitch camera. I’ve sold a few and once I get a studio space, I plan to make more. It’s fun creating these tools for others to make glitch art, even if they’re not technically inclined.

Circuit Bending: From Obsolete to Art

[10:38] BW: I read the Vice article about the creation of a piece you did called “Circuit Loop.” How much circuit bending have you done? I know it from the world of music, so I wasn’t entirely surprised to read about a circuit-bent camera. For example, Dan Deacon is a well-known circuit bender in the music world. Do you do a lot of circuit bending with different visual tools?

[11:30] DD: Not extensively. I’ve bought a few circuit devices, but many of them are older vintage equipment from the 70s and 80s. It’s expensive to purchase such equipment and then attempt to break it without actually ruining it. One wrong move during circuit bending can mean throwing away a $200 piece of equipment. However, I plan to explore more of this when I get a larger studio space, because I really enjoy exploring circuitry and discovering cool effects. I’ve also circuit-bent children’s audio toys or sound-making devices, which are fun and affordable.

[12:43] BW: That’s been my exposure to circuit-bent stuff as well, mainly circuit-bending children’s toys. How often do you use your circuit-bent cameras?

[13:05] DD: Quite often. I’ve probably created about a dozen pieces with them. I get bored easily, so I’ll experiment with a piece of equipment or a technique until I find a use for it. I have a huge toolkit of different techniques to use when the occasion arises, whether that’s for a scanner glitch, a circuit-bent camera, a JPEG corruption, or something else.

[13:49] BW: What’s the scanner glitch?

[13:51] DD: It’s a fun, easy process anyone can do with a flatbed scanner. You put a photograph, image, or assortment of objects on the scanner. While it’s scanning, you move them around to create a distorted effect on the scanner output.

Chemical Bending

[14:20] BW: Besides circuit bending, glitch art involves intriguing processes. You’ve done a series of works described as “chemical bent.” Could you tell me about this series and the process?

[14:42] DD: Absolutely. Even though it’s physically intensive, it’s one of my favorite techniques. I use old magazines, particularly National Geographics, Esquire, and Arizona Highways, which respond well to this process due to their ink or paper quality. I then apply a chemical called citrus Solv, a potent cleaner, onto the magazines. Make sure you’re in a well-ventilated area and wearing protective gear when doing this. The chemical begins dissolving and melting the inks in interesting ways. You can manipulate it further with paint brushes or blend pages from different magazines as the inks melt, creating detailed chemical striations. After scanning these pages, you’ll see small details that surpass the original magazines. Many pieces from that series are small cropped portions of a magazine page, but they look like a full, high-resolution piece.

[16:45] BW: Do you create a lot of analog artwork?

[16:54] DD: Not a ton. The majority of my work is digital due to accessibility reasons. However, for the chemical bending process, I trained an AI to generate those textures, minimizing my exposure to harsh chemicals.

[17:40] BW: That’s an intriguing approach. Have you trained many AI models? I assume it’s a diffusion model.

[17:47] DD: Yes, I’ve trained a few. I even released the chemical bending model. It’s not a full model but a small one that works quite well. It’s available for people to download. I’ve trained some general art models but I haven’t honed any that I’m truly pleased with to the point of releasing them. It’s a work in progress. Glitch art is broad, making it tricky to focus on one specific style.

[18:46] BW: Interesting. What other small AI models are out there? I’m familiar with the big three that most people use, but less so with trained models and how they circulate.

[19:11] DD: There are a few sites, like CivitAI, where people can train models and upload them for others to try, mix, and match. Currently, many are focusing on creating realistic and figurative graphic work, which is interesting. However, I prefer pursuing something less figurative. It seems everyone is trying to make anime-style characters.

[20:18] BW: I’m interested to see the potential as more artists become tech-savvy with building and training these models. What could happen when that level of creativity is unleashed and the friction is reduced?

[20:39] DD: Absolutely. We’re starting to see that with tools like Photoshop extending their AI capabilities. They’ve had AI elements in the program for a while, just not as noticeable.

[21:01] BW: So, it’s moving closer to the center now?

The Glitch Artists Collective

[21:07] DD: Yes, and I support that. The more accessible these tools become, the better. Many glitch artists appreciate this too. Unlike the closely guarded secrets of the photography world, glitch artists are often eager to share their techniques. With the Glitch Artists Collective, we even have a group dedicated to teaching new techniques, called “Tool Time”, where members are eager to share their discoveries.

[22:03] BW: The glitch art community has been especially fervent in adopting AI. Glitch artists were accustomed to using sources like Pexels and Pixabay for imagery. Now with AI, they’re able to generate their own source imagery. So, it’s understandable that they would embrace this new tool. But there’s an interesting parallel between the closely held secrets in photography and the AI world. How open is the glitch art community in sharing trade secrets with AI generation?

[23:11] DD: From my experience, they’ve been quite open. I’m part of a few Twitter group chats and Discord servers where everyone is eager to share about new AI tools, how to get specific output from new AI models, and so forth. For instance, with Runway, they just released their Generation Two, and I heard about it from my glitch art friends even before receiving the official email from Runway.

[23:52] BW: Have you used Runway much?

[23:55] DD: Yes, a bit. It’s enjoyable. Currently, they seem to prioritize ease of use without providing many options to tweak the output. But I’m hopeful that’ll change.

[24:20] BW: I’m curious, what have you been able to create with AI that you wouldn’t have considered otherwise?

[25:04] DD: I think it’s mostly sped up my process. I have a bit of 3D experience and have created works in 3D that took weeks due to the finickiness of 3D programs. AI has sped up that process, especially with videos and generating source material. As far as generating output from prompts, it’s definitely quicker— a few hours compared to weeks.

Darkstone Review

[25:56] BW: Can you tell me a bit about the Darkstone Review?

[26:00] DD: Sure, that was an early piece of teaser artwork on Hic et Nunc. It was essentially a zine I created that was like a puzzle, filled with unusual imagery. Hidden within this imagery was a puzzle people could solve. I offered a prize in NFT for the first person to figure it out. I’ve received only three messages from people claiming to have solved it. I love creating these kind of mysterious, ARG-like projects. It’s in the same vein as another project I had called Crypto Webcams. For a while, it was an anonymous project where I used images from unsecured webcams of businesses and institutions. I ensured not to post any photos with people in them or sometimes I’d photoshop them out. Later, I started incorporating AI into it, creating similar imagery, but perhaps with a hidden monster in the background. The first person to spot such an anomaly would receive a free NFT. Sometimes, the secrets were so well hidden, they were embedded into the code of the JPEG file itself.

Exploring Mass Surveillance

[28:05] BW: Wow, that’s going deep. So, this was a project using real unsecured webcams from actual businesses?

[28:17] DD: Yes. It was a commentary on mass surveillance, emphasizing how often we don’t even realize we’re under surveillance. These insecure cameras are out there on the internet, possibly capturing you walking down the street or working at your office.

[28:45] BW: Is this project still ongoing?

[28:48] DD: It’s on a bit of a hiatus. I’ve been really busy with my glitch work lately, but I plan to resume it when I have more downtime.

[29:01] BW: Where did the idea for that project come from?

[29:06] DD: I’ve always been fascinated by liminal spaces and backrooms. When I stumbled upon these types of scenes, it sparked something in my brain. A lot of it is set in these liminal spaces like airports or old warehouses. It feels like something you’re not supposed to see, which scratches a mysterious itch in my brain. The eerie quality of grainy footage also seems to resonate with a lot of people.

[29:54] BW: Have there been any legal ramifications or inquiries related to this?

[30:02] DD: No, not so far. I’m not a lawyer, but as far as I understand, the photographer, not the camera owner, owns the photos. I approached it as a photography project. While it’s a fascinating concept, I suppose if I received a cease and desist, it would be somewhat embarrassing on their part. It would draw attention to their insecure webcam monitoring their employees or similar situations.

The ‘Beyond Binary’ Exhibition

[30:53] BW: Right, what a cool project. I want to ask you about the “Beyond Binary” exhibition. You mentioned it earlier. What was your experience being recruited for this somewhat fraught venture? Could you tell us about the controversy surrounding the exhibit?

[31:23] DD: Sure, that’s a whole story on its own. A month or two before the exhibit, I received a message from the organizers. They’d posted on Twitter looking for glitch artists, and some people recommended me. They reached out, saying they wanted to do an exhibit on glitch art and wanted my help in educating their audience about it. I asked if I’d be included in the exhibit or receive a consultation fee, but they’d already curated the exhibit. They still wanted to talk, so I asked about consultation fees and then didn’t hear back. A month later, they tweeted about the show. The first image I saw was a piece from Rosa Menkman, an important figure in the glitch art community. But upon closer look, I didn’t see any of Rosa’s work. In fact, there were no women involved at all. It was an all-male show with over 20 artists, which felt wrong, especially in 2023. Glitch art has many founding figures who are women, non-binary, queer, and trans. A lot of people in both the glitch art and broader NFT communities noticed and criticized this. Some suggested I should curate the show. In response, the organizers paused the sale and brought in me and Mandy Chang to re-curate and diversify the show. However, it was frustrating at times. It felt like they were trying to do PR damage control and downplay the issue after that. Despite that, all artists curated into the show by Mandy and me sold well. The previously curated artists, not so much, but I think that was more due to the market conditions.

[36:04] BW: I’ve heard from others in the curation that it was a less than stellar experience with Sotheby’s. How do you feel about it looking back?

[36:29] DD: There were definitely frustrating points, but the key takeaway was the power of community. When we come together to fix something, our voices matter. It’s impressive that we, as a collective, managed to get such a long-standing institution as Sotheby’s to admit they’d messed up.

[37:01] BW: Indeed, it was pleasing to see how quickly they were taken to task and had to pause the exhibit. It was a week or two before they even announced the follow-up.

[37:21] DD: We had about two weeks to re-curate the show, which was really stressful. Technically, we only had a week or so to re-write the show—a significant task. Deena Tang was instrumental in this; she held Sotheby’s accountable. I’ve done a lot of curating work before, but nothing with an institution like Sotheby’s. It was a different world, signing 10,000-word contracts and such.

[38:24] BW: That sounds like a different world indeed. I want to ask about your creative process. Traditional art has a relatively intuitive creative process—sketches, early drafts, color palettes, research, etc. But glitch art seems different, working with volatile processes. Where does an idea start for a piece, and where does that idea take you? Given the numerous tools in your tool belt—your circuit-bent camera, different ways to corrupt files—how do you proceed? Does it start with an idea or just by messing around?

[39:55] DD: It varies. Sometimes it starts out with a specific idea and what emotion I want to convey. It’s very methodical. Other times, it’s more of a stream-of-consciousness approach, like, “Let’s see what happens when I do this.” So, sometimes it’s very experimentalist. But even when it is, there’s usually a guiding thread that I’m trying to follow. It may not always be conscious to me. Sometimes it’s more overt, like with the ‘Service’ piece, where I was trying to discuss specific disparities in the art industry.

[41:28] BW: When creating a piece that starts with an idea rather than improvisation, what form does that inspiration generally take? Is it a theme you want to communicate, a visual concept, or a story?

[41:59] DD: I’m often driven by themes or stories. I have bipolar disorder, so my mood heavily influences my approach. During manic periods, I’m more improvisational, creating a dozen or two dozen pieces in a month. In down states, I’m more reflective. When I hit art blocks, instead of fixating on my inability to create, I learned to focus on my wellbeing. I set aside art, play video games, take nature walks, and focus on improving my state of mind. Ultimately, inspiration comes from living life and our experiences.

Surviving Art Blocks

[43:50] BW: Could you share more about your self-care routines or tools during these down moments?

[44:07] DD: It’s about focusing on taking care of oneself. Ensuring you’re eating well, maintaining hygiene, cleaning up your environment, even if it’s just a corner of a room, can give a sense of satisfaction. I also lean on my interpersonal relationships. For instance, I turn to my wife, Abby, when I’m feeling down. Distractions like video games or watching an anime also help.

[45:31] BW: I’ve spoken with many artists about their periods of ups and downs and how they manage their mental health. Some lean into it and create art from that place, some use art as therapy, while others need to step away for a while. I think the approach depends on the individual and the nature of their depressive episode. I appreciate you sharing your experience. Now, I’m curious about any tactical advice you could offer to artists looking to transition from part-time to full-time artmaking. What is the creative process behind building a creative career?

[46:55] DD: It’s a complex subject and the process will be unique for everyone. Factors such as where you’re at in your career, your capabilities, and what you want to do all come into play. However, one common piece of advice I can offer is to find your community. It may sound cliché, but it works. The more niche, the better. While it’s beneficial to make many connections in the broader web three community, it’s also important to find a small, tight-knit group. These are the people you can rely on during tough times, like when you’re having a bad day or taking a break from social media. They’ll be there to support and motivate you. If you can’t find the community you’re looking for, it’s perfectly fine to create your own and like-minded people will gravitate towards it.

[48:37] BW: I struggle with maintaining consistent interaction online. I’m subscribed to many Discord servers, but I rarely check in on them. It’s also been a challenge to find individuals in these communities who resonate with my perspective. I think there are many others who find engaging in online communities unnatural. So, do you have any tips or best practices on how to engage, stay engaged, and find your tribe?

[49:45] DD: I understand what you’re saying; I’m naturally more introverted, so being more social was a big step for me. I had the advantage of already being part of the glitch art community before NFTs, so when many from that community joined web three, it felt like I had a built-in community. Also, many queer artists in web three have formed their own communities. However, in terms of actionable tips, don’t try to force it. If you’re not vibing with a community, feel free to leave that Discord server. You don’t have to announce your departure or burn bridges. It’s not feasible to try to connect with thousands of people. I recently unfollowed a large number of accounts I was following because many were bots or inactive projects. You can certainly pare down your list and focus on those you vibe with and want to build a community with because forcing it will never work.

Listen to the episode on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Overcast, iHeart, PlayerFM, Podchaser, Boomplay, Tune-In, Podbean, Google Podcasts, Amazon Music, or on your favorite podcast platform.

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Automotive / EVs, Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- BlockOffsets. Modernizing Environmental Offset Ownership. Access Here.

- Source: https://rare.makersplace.com/2023/07/20/transcript-e13-dawnia-darkstone-the-art-of-breaking-things/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=transcript-e13-dawnia-darkstone-the-art-of-breaking-things

- :has

- :is

- :not

- :where

- $UP

- 07

- 10

- 11

- 12

- 13

- 14

- 15%

- 16

- 17

- 19

- 20

- 20 years

- 2023

- 22

- 23

- 24

- 25

- 26

- 28

- 30

- 31

- 36

- 39

- 3d

- 40

- 46

- 49

- 50

- 51

- 7

- 8

- a

- ability

- Able

- About

- about IT

- Absolute

- absolutely

- acceleration

- accessibility

- accessible

- accidents

- accountable

- Accounts

- actual

- actually

- admit

- Adopting

- ADvantage

- advice

- affect

- affordable

- After

- ago

- AI

- ai art

- Airports

- All

- already

- also

- always

- am

- Amazon

- an

- and

- Anime

- Announce

- announced

- Anonymous

- Another

- any

- anyone

- appealing

- Apple

- Apply

- appreciate

- approach

- ARE

- AREA

- arizona

- around

- Art

- Art Blocks

- Art Show

- article

- artist

- Artists

- artwork

- AS

- assortment

- assume

- At

- attention

- audience

- audio

- Automatic

- available

- away

- back

- background

- Bad

- Basically

- BE

- because

- become

- been

- before

- Beginners

- behind

- being

- beneficial

- Benjamin

- besides

- BEST

- best practices

- Better

- between

- Beyond

- Big

- Bit

- Blend

- blockchain

- Blocks

- Bored

- borrow

- both

- bots

- bought

- Brain

- Break

- Breaking

- bridges

- broad

- broader

- Broken

- brought

- build

- Building

- built-in

- burn

- businesses

- busy

- but

- by

- called

- came

- camera

- cameras

- CAN

- capabilities

- Capturing

- car

- care

- Career

- Cease and Desist

- Center

- certainly

- challenge

- chang

- change

- characters

- cheap

- check

- chemical

- chemicals

- child

- claiming

- class

- Cleaning

- closely

- closer

- code

- Collective

- color

- come

- comes

- Commentary

- Common

- Common Piece

- communicate

- Communities

- community

- compared

- complex

- complicated

- concept

- concert

- conditions

- Connect

- Connections

- conscious

- considered

- consistent

- consultation

- contracts

- control

- controls

- controversy

- Conversation

- convert

- converting

- Cool

- Corner

- Corruption

- could

- Couple

- create

- created

- Creating

- creation

- Creative

- creativity

- crypto

- curated

- curating

- curation

- curious

- Currently

- damage

- data

- day

- dedicated

- deep

- definitely

- depends

- described

- designed

- Despite

- detailed

- details

- Devices

- DID

- difference

- different

- Diffusion

- digital

- directly

- discord

- discovered

- discovering

- discuss

- disorder

- diversify

- do

- does

- doing

- done

- Dont

- down

- download

- downs

- downtime

- dozen

- draw

- dream

- driven

- due

- during

- E&T

- eager

- Earlier

- Early

- ease

- ease of use

- easily

- easy

- editing

- Editorial

- educating

- effect

- effects

- either

- elements

- else

- embedded

- embrace

- emphasizing

- employees

- end

- engage

- engaged

- engaging

- enjoy

- enjoyable

- ensuring

- entirely

- Environment

- episode

- equipment

- especially

- essentially

- etc

- Ethos

- Even

- Event

- events

- everyone

- everything

- example

- excited

- exhibit

- exhibition

- expensive

- experience

- Experiences

- experiment

- explore

- Exploring

- Exposure

- express

- extending

- extensively

- fact

- factors

- fairly

- familiar

- far

- fascinating

- Favorite

- feasible

- featured

- fee

- feel

- Fees

- few

- Figure

- Figures

- File

- Files

- filled

- Find

- finding

- fine

- First

- fit

- five

- Fix

- Focus

- focusing

- follow

- following

- For

- Force

- form

- format

- formed

- forth

- found

- founding

- Free

- friction

- friends

- from

- frustrating

- full

- fun

- further

- fusion

- Games

- Gear

- General

- generally

- generate

- generating

- generation

- get

- getting

- Give

- given

- glitch

- going

- good

- Google’s

- Group

- had

- happen

- happens

- Hard

- Hardware

- Have

- having

- Health

- hear

- heard

- heavily

- Held

- help

- helped

- here

- Hidden

- high-resolution

- highways

- Hit

- hopeful

- HOURS

- How

- How To

- However

- HTTPS

- huge

- i

- I’LL

- idea

- if

- image

- images

- import

- important

- impressive

- improving

- in

- inability

- inactive

- Inclined

- included

- incorporate

- incorporating

- individual

- individuals

- industry

- inexpensive

- Inquiries

- insecure

- Inspiration

- inspired

- instance

- instead

- Institution

- institutions

- instrumental

- interaction

- interested

- interesting

- Internet

- into

- intriguing

- introduce

- intuitive

- involved

- issue

- IT

- iteration

- iterations

- ITS

- itself

- joined

- joining

- joining us

- jump

- just

- Key

- kids

- Kind

- Know

- Knowing

- known

- korea

- large

- larger

- Last

- later

- lawyer

- learned

- Leave

- Legal

- less

- Level

- Life

- like

- like-minded

- List

- living

- local

- long-standing

- Look

- look like

- looking

- losing

- lost

- Lot

- love

- magazine

- magazines

- mainly

- maintaining

- Majority

- make

- Making

- manage

- managed

- many

- Market

- market conditions

- Mass

- Match

- material

- Matter

- May..

- me

- mean

- Media

- Members

- mental

- Mental health

- mentioned

- message

- messages

- methodical

- might

- mind

- minimizing

- mix

- model

- models

- Moments

- monitoring

- Month

- mood

- more

- most

- mostly

- move

- moving

- much

- Music

- my

- mysterious

- National

- Nature

- Need

- never

- New

- NFT

- NFTs

- nice

- no

- nothing

- now

- number

- numerous

- objects

- obsolete

- occasion

- of

- offer

- offered

- Office

- official

- often

- Old

- older

- on

- once

- ONE

- ongoing

- online

- online communities

- only

- open

- Options

- or

- organizers

- original

- Other

- Others

- otherwise

- our

- out

- output

- over

- own

- owner

- owns

- page

- pages

- paint

- Paper

- Parallel

- part

- particularly

- patrick

- pause

- People

- perhaps

- periods

- person

- perspective

- photographer

- photography

- Photos

- photoshop

- Physically

- piece

- pieces

- Place

- plan

- platform

- plato

- Plato AiStream

- Plato Data Intelligence

- PlatoAiCast

- PlatoData

- Play

- please

- pleased

- plugins

- podcast

- Point

- points

- Poke

- possibly

- Post

- posted

- potential

- power

- pr

- practice

- practices

- prefer

- preparing

- presentation

- previously

- Prioritize

- prize

- probably

- process

- processes

- produce

- Profile

- Program

- Programs

- Progress

- project

- projects

- Protective

- providing

- purchase

- put

- puzzle

- quality

- Questions

- quickly

- rarely

- rather

- Raw

- raw data

- reached

- Read

- real

- realistic

- realize

- really

- reasons

- receive

- received

- receiving

- recently

- recommended

- Red

- Reduced

- related

- relation

- Relationships

- relatively

- released

- releasing

- rely

- research

- Resonate

- Respond

- response

- Results

- resume

- review

- right

- Room

- ROSA

- Run

- runway

- Said

- sale

- same

- satisfaction

- saw

- say

- saying

- scanning

- scenes

- see

- seem

- seems

- sense

- Series

- set

- Share

- sharing

- she

- shooting

- should

- show

- significant

- signing

- similar

- since

- Sites

- Sitting

- situations

- small

- So

- so Far

- Social

- social media

- Software

- sold

- SOLVE

- some

- something

- somewhat

- Sound

- Source

- Sources

- South

- South Korea

- Space

- spaces

- sparked

- Speaks

- specialize

- specialized

- specific

- spoken

- Spot

- Spotify

- stabilize

- stable

- start

- started

- Starting

- starts

- State

- States

- stay

- Stellar

- Step

- Still

- Stories

- Story

- straightforward

- street

- strong

- Struggle

- studio

- style

- subject

- such

- Super

- support

- supposed

- sure

- surpass

- surprised

- Surrounding

- surveillance

- tactical

- Take

- taken

- taking

- Talk

- Task

- Teaching

- teaser

- Technical

- technically

- techniques

- Technology

- tell

- terms

- than

- thank

- thanks

- that

- The

- the world

- their

- Them

- theme

- then

- therapy

- There.

- These

- they

- things

- think

- this

- those

- though?

- thousands

- three

- Throwing

- time

- times

- tips

- to

- today

- together

- Ton

- too

- took

- tool

- toolkit

- tools

- tough

- towards

- trade

- traditional

- Train

- trained

- Training

- Transcript

- transition

- Tribe

- truly

- try

- TURN

- tutorials

- two

- types

- Ultimately

- under

- understand

- understandable

- unique

- unleashed

- unlike

- unsecured

- until

- unusual

- upon

- UPS

- us

- use

- used

- using

- usually

- venture

- Venue

- very

- via

- Vibe

- vice

- Video

- video games

- Videos

- View

- vintage

- VOICES

- volatile

- walker

- walking

- Wall

- want

- wanted

- was

- watching

- Way..

- ways

- we

- web

- Web3

- webcam

- week

- Weeks

- WELL

- well-known

- wellbeing

- were

- What

- What is

- when

- whether

- which

- while

- WHO

- whole

- wife

- Wild

- will

- with

- within

- without

- Women

- Work

- worked

- working

- works

- world

- would

- WoW

- Wrong

- years

- yes

- you

- Your

- yourself