It’s 1933, and chemical company magnate Richard Milton Hollingshead Jr. of Camden, New Jersey has a dilemma. Hollingshead worked at the R.M. Hollingshead Corp. chemical plant in Camden, a company started by his father producing automotive, livery and household products — mostly polishes, cleaners, grease, dyes and other items under the Whiz brand name.

A big, fat problem

But in an era before television or the internet, and with radio still in its ascendancy, Hollingshead’s mother loved to go watch movies at the movie theater, but she’s too fat to fit comfortably in a theater seat. He gives it some thought and comes up with an idea.

He ties some bedsheets together and attaches them to trees in his backyard. With his mother sitting in a car, he places a 1928 Kodak projector on the hood and shows a movie.

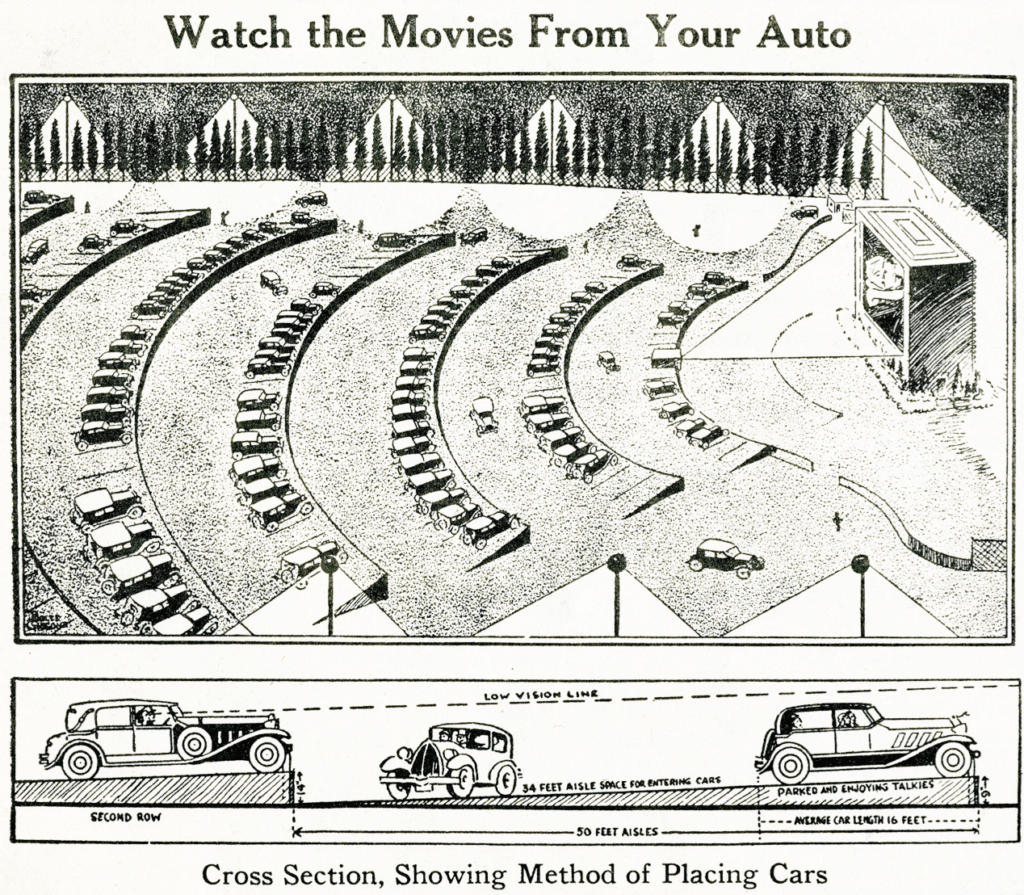

Given that Hollingshead was an auto parts salesman, the concept of watching a film from the comfort of your car took hold, and he begins experimenting with car parking layouts to ensure that everyone has a view by placing blocks under the front wheels of cars in back so that they could see over the cars in front of them. Securing $30,000 in financial backing from his cousin, Willis W. Smith, Hollingshead forms Park-In Theaters Inc., and he applies for a patent on his idea in 1932.

“My invention relates to a new and useful outdoor theater, whereby the transportation facilities to and from the theater are made to constitute an element of the seating facilities,” Hollingshead writes on his application. By this week in 1933, he receives his patent, and the drive-In movie theater is born.

The first drive-in

Buying a 10-acre parcel on Admiral Wilson Boulevard in Pennsauken, New Jersey, Hollingshead’s new Camden Drive-In has room for 500 cars, which can view the 40-foot-by-50-foot screen, which is augmented by three 6-foot speakers made by RCA Victor, then located in Camden as well.

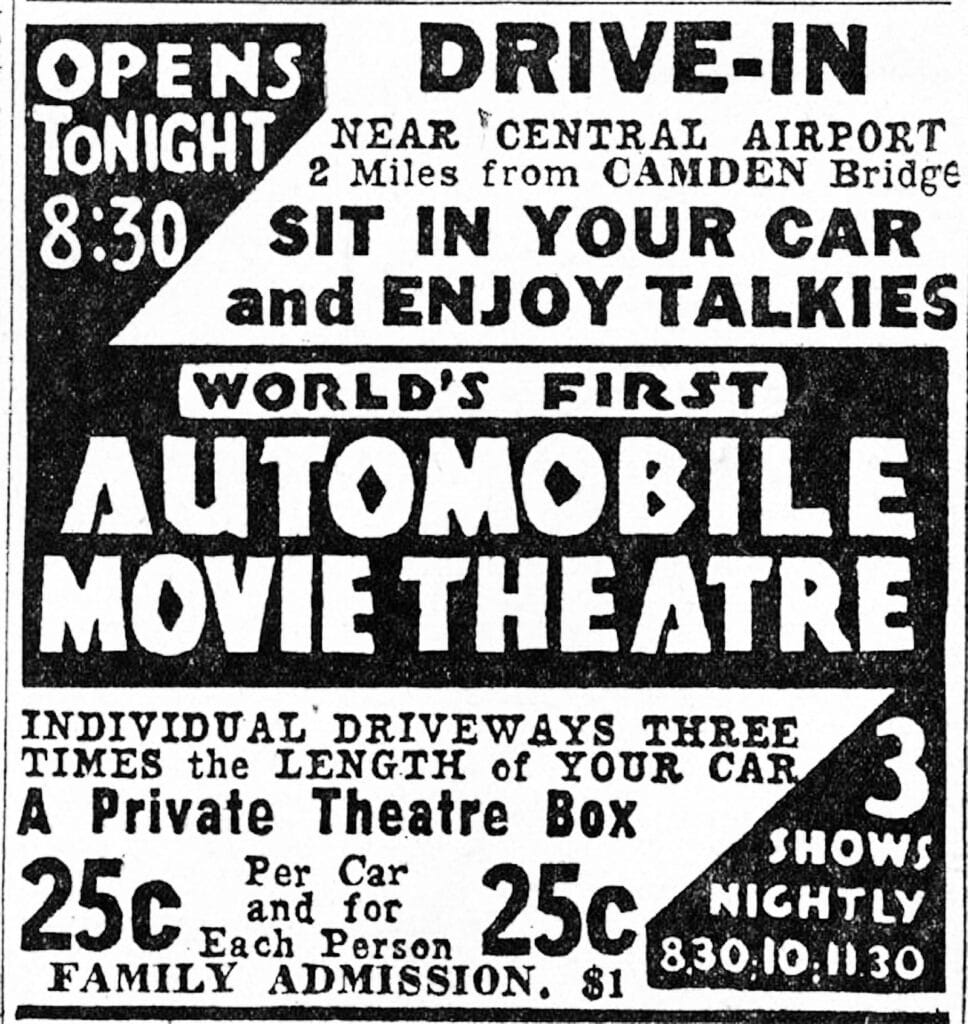

A local advertisement for his new venture appears proclaiming, “sit in your car and hear movies” and “world’s first automobile theatre,” which indeed it was. Admission was 25 cents per car, plus 25 cents per person, up to $1 max. There were three showings: 8:30, 10 and 11:30 p.m.

Ironically, the first movie shown at this all-American concept was a British film, “Wives Beware,” starring Adolphe Menjou as as a man in an unhappy marriage who fakes amnesia to pursue extramarital affairs. The showings sold out that first night, and by the end of the summer, cars from 43 states had visited his new venture.

But Hollingshead closed his operation 14 months later due to lack of profit. Given his theater wasn’t owned by a Hollywood movie studio, a common practice at the time, he had to pay upwards of $400 for each film, many of which had already been screened at conventional theatres.

By then, William Shankweiler opened what would be the second drive-in movie theatre in Oresfield, Pennsylvania, northwest of Allentown. Shankweiler’s Drive-In Theatre survives to this day, and is the nation’s oldest remaining drive-in.

But Hollsngshead concept is not initially embraced. By 1939, only 17 drive-in movie theaters had opened nationwide. As it turns out, sound is proving to be a problem as it infiltrates nearby neighborhoods. It’s resolved once RCA Victor creates speakers that mount on car windows.

A Mid-Century phenomenon

Drive-ins would take off, but not until Hollingshead’s patent is overturned in 1949. This results in more than 4,500 drive-in theaters opening from 1948 through 1955, offering a family night out at an affordable price. And at a time when people dressed up to go to the theater, there was no need to while sitting in your car at night.

Among the largest drive-ins was the 28-acre All-Weather Drive-In of Copiague, New York, which featured parking space for 2,500 cars, indoor seating for 1,200, as well as a playground, and restaurant. Other drive-ins offered such amenities as swimming pools, laundromats and in-car heaters. By 1960s, they had become a teenage hangout, a moment captured in song by The Beach Boys on their 1964 album “All Summer Long.”

But by the 1970s, their popularity begins to decline for several reasons. An indoor theater can show a film five or six times a day, instead of only a couple times a night like a drive-in. This causes movie studios to send their best films there, reserving lower-quality B-pictures for drive-ins. As families increasingly abandon their cars for air-conditioned movie theatres, particularly as gas prices skyrocket in the 1970s, drive-ins increasingly turn to slasher films and X-rated fare to survive. Its exacerbated by teens hanging out at malls, or families watching movies on their VCRs.

But there efforts to save them most notably Honda’s Project Drive-In, an effort to save as many of America’s remaining drive-ins as possible by helping to raise money to cover the cost of isntalling a digital projector as 35mm film distribution came to an end about a decade ago. The changeover was costly, as the vast majority of drive-ins are mom-and-pop operations. The project was successful at helping about a dozen theaters.

Yet they survive

While not nearly as common as they once were, drive-in theatres still survive. According to the United Drive-In Theatre Owners Association, there are 302 drive-ins in the United States with 533 screens.

That said, some states lack them entirely, including Alaska (no surprise there), Arkansas, Delaware, Hawaii, Louisiana, New Mexico and North Dakota. But if you’re looking for one, head to New York state. There you’ll find 28 surviving, the most of any state, followed by Pennsylvania with 27, and Ohio with 24.

Most recently, during the start of pandemic, drive-ins experienced a resurgence as the perfect solution to a night out with social distancing.

That said, Hollingshead never made any money from his patent.

Most new drive-in theaters ignored his patent, costing him huge legal fees, but few royalties. But his other businesses more than made up for it, and his company was the third-largest employer in Camden by the early 1970s, manufacturing automotive products.

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Data Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- Minting the Future w Adryenn Ashley. Access Here.

- Buy and Sell Shares in PRE-IPO Companies with PREIPO®. Access Here.

- Source: https://www.thedetroitbureau.com/2023/05/the-rearview-mirror-the-first-drive-in-movie-theater/

- :has

- :is

- :not

- ][p

- $UP

- 000

- 1

- 10

- 11

- 14

- 1933

- 1949

- 200

- 24

- 27

- 28

- 30

- 500

- 8

- a

- About

- According

- Advertisement

- Affairs

- affordable

- ago

- alaska

- Album

- already

- amenities

- america

- an

- and

- any

- Application

- ARE

- arkansas

- AS

- At

- attempted

- augmented

- auto

- automobile

- automotive

- back

- backing

- BE

- Beach

- become

- been

- before

- BEST

- Beware

- Big

- Blocks

- born

- brand

- British

- Bureau

- businesses

- but

- by

- came

- CAN

- car

- cars

- causes

- chemical

- closed

- comes

- comfort

- Common

- company

- concept

- constitute

- conventional

- Corp

- Cost

- could

- Couple

- cover

- creates

- Dakota

- day

- decade

- Decline

- Delaware

- digital

- distribution

- dozen

- due

- during

- each

- Early

- effort

- efforts

- element

- embraced

- end

- ensure

- entirely

- Era

- everyone

- experienced

- facilities

- families

- family

- Fat

- featured

- Fees

- few

- Film

- films

- financial

- Find

- First

- fit

- followed

- For

- forms

- from

- front

- GAS

- gas prices

- given

- gives

- Go

- had

- hawaii

- he

- head

- hear

- helping

- him

- his

- hold

- Hollywood

- hood

- household

- HTML

- HTTPS

- huge

- idea

- if

- in

- Inc.

- Including

- increasingly

- Indoor

- initial

- initially

- instead

- Internet

- Invention

- IT

- items

- ITS

- Jersey

- jpg

- Lack

- largest

- later

- Legal

- like

- local

- located

- Long

- looking

- Louisiana

- loved

- made

- Majority

- man

- manufacturing

- many

- max

- max-width

- Mexico

- Milton

- mirror

- money

- months

- more

- most

- mostly

- mother

- MOUNT

- movie

- Movies

- name

- Nations

- Nationwide

- nearly

- Need

- never

- New

- New Jersey

- New York

- New York state

- night

- no

- North

- North Dakota

- notably

- of

- off

- offered

- offering

- Ohio

- oldest

- on

- once

- ONE

- only

- opened

- opening

- operation

- Operations

- or

- Other

- out

- Outdoor

- over

- owned

- owners

- pandemic

- parking

- particularly

- parts

- patent

- Pay

- Pennsylvania

- People

- perfect

- person

- Places

- placing

- plato

- Plato Data Intelligence

- PlatoData

- plus

- Pools

- popularity

- possible

- practice

- price

- Prices

- Problem

- Products

- Profit

- project

- pursue

- Radio

- raise

- reasons

- receives

- recently

- remaining

- resolved

- restaurant

- Results

- Richard

- Room

- royalties

- Said

- Salesman

- Save

- Screen

- screens

- Second

- securing

- see

- send

- several

- show

- SHOWINGS

- shown

- Shows

- Sitting

- SIX

- skyrocket

- So

- Social

- social distancing

- sold

- solution

- some

- Sound

- Space

- speakers

- start

- started

- State

- States

- Still

- studio

- studios

- successful

- such

- summer

- surprise

- survive

- swimming

- Swimming Pools

- Take

- Teens

- television

- than

- that

- The

- Theater

- theatre

- their

- Them

- then

- There.

- they

- this

- this week

- thought

- three

- Through

- Ties

- time

- times

- to

- together

- too

- took

- transportation

- Trees

- TURN

- turns

- under

- United

- United States

- until

- upwards

- Vast

- venture

- View

- visited

- W

- was

- Watch

- watching

- week

- WELL

- were

- What

- when

- which

- while

- WHO

- willis

- Wilson

- windows

- with

- worked

- would

- york

- Your

- youtube

- zephyrnet