This week in 1947, the first production Kaiser and Frazer automobiles roll off the Willow Run, Michigan assembly line. Until the modern EV startups such as Tesla, Rivian and Lucid, it would be the last American automaker to challenge the Big Three, and would survive through 1970.

If the names seem foreign to modern automotive buyers, they were famous at the time. Nevertheless, the only remnant of the automaker is Kaiser Permanente, the HMO many Americans use.

But the saga of Kaiser-Frazer, and its creation, is a fascinating one.

A case of the WIllys

The story of Kaiser-Frazer is entwined with Willys-Overland that for a time in the 1920s, ranked second only to Ford in sales. But management mistakes found it declaring bankruptcy in 1933, and exiting four years later. Although the company produced more than 60,000 cars and netted a profit of $473,000 in 1937, the journey into bankruptcy didn’t instill buyer confidence, and the company’s fortunes declined once more.

It’s only under the stewardship of sales manager Joseph Frazer that the company didn’t fail once more. While car sales remained meager, Frazer had won a U.S. Army contract to build the Jeep, leading to a profit in 1941 of $809,258, and a backlog of $42.5 million in defense orders. Willys-Overland profited along with the war, as dollar volume grew from $21 million in 1941 to $213 million in 1944.

But it was in 1942 that Frazer first became aware of Henry J. Kaiser, who had been studying plastic-bodied cars, suggesting that once World War II was over, he might sell them for $400-$600, while also saying that automakers should publicize their postwar plans.

Frazer was not happy; automobile production had been halted as automakers were expected to convert their factories to manufacture munitions, not automobiles.

“I resent a West Coast shipbuilder asking us if we have the courage to plan postwar automobiles when the President has asked us to forego all work which would take away from the war effort,” he said.

Little did either one of them know that within three years, they would be business partners.

A meeting of like minds

Kaiser had made his mark as a shipbuilder on the West Coast during the war while Frazer had made his mark at Willys-Overland. By the time Frazer left Willys-Overland in 1944, the company had yearly sales of $212 million, thanks to Jeep production. But by that point, Frazer had landed at Graham-Paige, where he was planning the firm’s postwar automobile. That Graham-Paige had survived at all was miraculous.

Before the war, the company had limped long, an unprofitable automaker that had survived building the Graham Hollywood based on old Cord 810. The war had proven profitable, however, and 1941 provided the first profits since 1933. Once more on sound footing, Frazer assumed control of Graham-Paige after purchasing 530,000 shares of company stock in 1944 from founder Joe Graham, with options on an additional 300,000. Not surprisingly, Frazer was elected chairman of the Graham-Paige board, and started planning a postwar car.

Frazer brought in designer Howard Darrin to work on the new car, which to be called Frazer, as the Graham-Paige name no longer carried much weight with buyers. As dealers were being recruited, Frazer was introduced to Henry Kaiser by Amadeo P. Giannani, founder of Bank of America. Kaiser, who had revolutionized shipbuilding, had been toying with the idea of an affordable postwar car. Like others in the industry, Kaiser expected a postwar recession like the one that followed World War I.

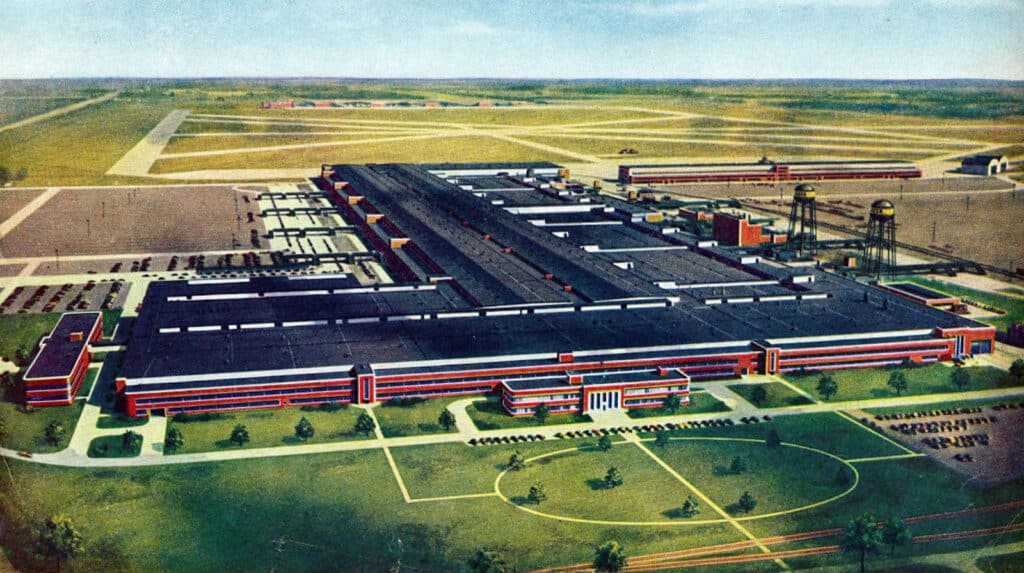

But Kaiser had no automotive experience; Frazer, whoever, did. The two joined forces, agreeing to a joint venture as Frazer’s nephew, Hickman Price Jr., obtained the wartime surplus Willow Run, Michigan assembly plant that Ford no longer wanted. Next came Kaiser-Frazer’s stock offering which netted the company $52 million in capitalization.

A complex joint operating agreement between Kaiser-Frazer and Graham-Paige was agreed to, with two mainstream Kaisers automobiles to be built for every premium Frazer, the latter remaining a Graham-Paige product. Joe Frazer was named president of both companies, while Henry Kaiser was anointed chairman of Kaiser-Frazer.

By January 1946, Kaiser-Frazer unveiled their first prototype, the front-wheel drive Kaiser K85 at the Waldorf-Astoria in New York City. But development problems precluded its use, as the car exhibited heavy steering, gear whine, and wheel shimmy. The decision was made that both Kaiser and Frazer cars would share powertrains and looks, as Henry Kaiser used Graham’s design for his own car in a fit of expediency, not artistry.

Too much too soon

The first Kaiser and Frazer cars rolled off the line this week in 1947, both powered by a 3.7-liter 6-cylinder engine that produced 100 horsepower. The Frazer was the fancier of the two, and offered as a sedan or convertible. But the two differed in more than furnishings. The Frazer benefitted from its automatic transmission, while the Kaiser came with a 3-speed manual transmission. Rear-wheel drive was standard on both cars.

Initially, the cars sold well in the postwar seller’s market, with Kaiser-Frazer producing 70,000 vehicles in 1947 and nearly 92,000 in 1948, good for a $30 million profit. Yet neither car was cheap. The Kaiser Special started at nearly $700 more than the cheapest 1947 Chevrolet, while the upscale 6-cylinder Frazer cost $100 more than an 8-cylinder Buick Special.

Yet as demand became satiated, the Big Three geared up for their first, true postwar designs in 1949. In contrast, Kaiser-Frazer merely had a refresh; a new model was due in 1950. Yet Henry Kaiser wanted to build 200,000 cars, against Frazer’s desire to pull back in the face of the Big Three’s redesign.

“The Kaisers never retrench,” he insisted, and the company followed Henry’s wishes, gearing up to build 200,000 cars — and sold 58,000. Approximately 20% remained unsold, and were given new 1950 serial numbers, accounting for about 84% of 1950 sales.

It was too much for Frazer, who left the company and was replaced by Henry’s son, Edgar. The Frazer line was dropped.

The end, and a new beginning

A new Kaiser arrived in 1951, with a new design by Darrin. But it did little to help sales, which continued to slide, totaling 32,000 for 1952 and 28,000 for 1953. But instead of restyling the Kaiser, or manufacturing a V-8 to match the competition, the company introduced the compact Henry J, which proved to be flop. Even America’s first fiberglass sports car, the Kaiser-Darrin, failed to elicit buyers.

By 1954, with cash diminishing, Kaiser acquires Willys-Overland for $63 million and renamed Willys Motors. Kaiser production was consolidated at Willys Toledo plant, with Kaiser selling its Willow Run facility to General Motors in 1954 for $24 million. Many Kaiser dealers become Jeep dealers as tooling for the 1954 Kaisers was saved and moved to Industrias Kaiser Argentina, where it was sold as the Kaiser Carabela through 1962.

Back in the states, Kaiser returned Willys Motors to profitability by 1956, renaming it Kaiser Jeep Corp. in 1962. It would be sold to American Motors Corp. in 1970 after Henry’s death in 1969.

Many view Henry Kaiser’s car-building career as a failure, which is true if your tunnel vision stops at 1954. But the following 15 years proved far more successful than the previous eight, meriting a re-examination of his skill as an auto manufacturer.

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Data Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- Minting the Future w Adryenn Ashley. Access Here.

- Buy and Sell Shares in PRE-IPO Companies with PREIPO®. Access Here.

- Source: https://www.thedetroitbureau.com/2023/06/the-rearview-mirror-americas-last-new-automaker-before-tesla/

- :has

- :is

- :not

- :where

- ][p

- $UP

- 000

- 100

- 15 years

- 15%

- 1933

- 1949

- 1951

- 200

- 28

- 60

- 70

- a

- About

- Accounting

- Acquires

- Additional

- affordable

- After

- against

- agreeing

- Agreement

- All

- along

- also

- Although

- america

- American

- Americans

- an

- and

- approximately

- Argentina

- Army

- AS

- Assembly

- assumed

- At

- auto

- automakers

- Automatic

- automobile

- automobiles

- automotive

- aware

- away

- back

- Bank

- Bank of America

- Bankruptcy

- based

- BE

- became

- become

- been

- before

- being

- between

- Big

- board

- both

- brought

- build

- Building

- built

- Bureau

- business

- but

- BUYER..

- buyers

- by

- called

- came

- capitalization

- car

- Career

- carried

- cars

- case

- Cash

- chairman

- challenge

- cheap

- cheapest

- Chevrolet

- City

- Coast

- Companies

- company

- Company’s

- competition

- complex

- confidence

- continued

- contract

- contrast

- control

- convert

- Corp

- Cost

- creation

- credit

- Death

- decision

- Defense

- Demand

- Design

- Designer

- designs

- Development

- DID

- diminishing

- Dollar

- drive

- dropped

- due

- during

- effort

- either

- elected

- end

- Engine

- EV

- Even

- Every

- Exiting

- expected

- experience

- Face

- Facelift

- Facility

- factories

- FAIL

- Failed

- Failure

- famous

- far

- fascinating

- final

- First

- fit

- followed

- following

- For

- Forces

- Ford

- foreign

- fortunes

- found

- founder

- four

- from

- Gear

- geared

- gearing

- General

- General Motors

- given

- good

- had

- happy

- Have

- he

- heavy

- help

- henry

- his

- Hollywood

- However

- HTTPS

- i

- idea

- if

- ii

- in

- industry

- instead

- interior

- into

- introduced

- IT

- ITS

- January

- jeep

- joined

- joint

- joint venture

- journey

- jpg

- Know

- Last

- later

- leading

- left

- like

- Line

- little

- Long

- longer

- LOOKS

- lucid

- made

- Mainstream

- management

- manager

- manual

- Manufacturer

- manufacturing

- many

- mark

- Market

- Match

- max-width

- meeting

- merely

- Michigan

- might

- million

- mirror

- mistakes

- model

- Modern

- more

- Motors

- much

- name

- Named

- names

- nearly

- Neither

- never

- Nevertheless

- New

- New York

- new york city

- next

- no

- numbers

- obtained

- of

- off

- offered

- offering

- Old

- on

- once

- ONE

- only

- operating

- Options

- or

- orders

- Others

- over

- own

- partners

- plan

- planning

- plans

- plato

- Plato Data Intelligence

- PlatoData

- Point

- powered

- Premium

- president

- previous

- price

- problems

- Produced

- Product

- Production

- Profit

- profitability

- profitable

- profited

- profits

- prototype

- proved

- proven

- provided

- purchasing

- ranked

- receiving

- recession

- redesign

- remained

- remaining

- replaced

- revolutionized

- rivian

- Roll

- Rolled

- Run

- s

- saga

- Said

- sales

- saying

- Second

- seem

- sell

- Selling

- serial

- Share

- Shares

- should

- since

- skill

- Slide

- sold

- son

- Sound

- special

- Sports

- standard

- started

- Startups

- States

- Stewardship

- stock

- Stops

- Story

- Studying

- successful

- such

- surplus

- survive

- Survived

- Take

- Tesla

- than

- thanks

- that

- The

- The West

- their

- Them

- they

- this

- this week

- three

- Through

- time

- to

- too

- true

- two

- u.s.

- under

- until

- unveiled

- us

- use

- used

- Vehicles

- venture

- View

- vision

- volume

- wanted

- war

- was

- we

- week

- weight

- WELL

- were

- West

- Wheel

- when

- which

- while

- WHO

- whoever

- wishes

- with

- within

- Won

- Work

- world

- would

- yearly

- years

- yet

- york

- Your

- zephyrnet