One of the more romantic notions of how we can address climate change while tackling the problem of biodiversity loss is rewilding. The concept calls for essentially removing humans from the ecosystem and letting nature take its course. Rewilding is a bit different from ecosystem restoration through human intervention but can have similar results.

The ultimate aim of rewilding is to step back and let nature recreate self-sustaining ecosystems that ultimately serve humanity by providing clean air and water, carbon sequestration, the prevention of soil erosion, pollinators for our food and dozens of other essential services. Rewilding can allow nature to recharge and help provide these critical resources — on which many businesses directly and indirectly depend.

Rewilding can have myriad impacts

America is a big place, so changing land use could have a big impact on the environment and quality of life not just here but around the world.

Let’s consider land use, particularly land used for livestock production. About 41 percent of all U.S. land is used to care for livestock. Over two out of every five acres of the 1.9 billion acres of land in the contiguous lower 48 states in the U.S. are used just to raise the food we eat. The story is similar in other countries, as nearly 60 percent of the world’s agricultural land is used for beef production. This is wildly inefficient, because beef accounts for only about 2 percent of the total calories humans consume.

The ultimate aim of rewilding is to step back and let nature recreate self-sustaining ecosystems that ultimately serve humanity …

The environmental damage from beef production is well documented. It uses a lot of land and is a major contributor to the clearing of land in the Amazon and other rainforests. Beef production is also very water intensive, putting stress on the water resources. Cattle emit methane, a powerful greenhouse gas — so the more of them, the bigger the greenhouse gas emissions problem. What’s more, feeding cattle requires devoting lots of land to monoculture crops such as soybeans and corn, which often results in soil degradation, chemical pollution from pesticides and the use of more fertilizers and fuel.

Time for a thought experiment

Let’s say for the sake of argument that over the next decade, the United States decreased beef consumption by 10 percent. That would potentially free up about 4-5 percent of U.S. land for rewilding. (I just used 10 percent of the 41 percent of land the U.S. uses for beef production to arrive at that number.) Not all of this hypothetical land would automatically be rewilded, but humor me for this thought experiment.

Rewilding 4-5 percent of America’s land would allow trees and grasslands to recover, serving as a carbon sink. A move away from beef would relieve the stress on America’s rivers, especially the Colorado River. Less cropland used for animal feed would lower the use of pesticides that run off into America’s waterways, making these waterways healthier and more able to support their own ecosystems. Less cattle would mean less methane, lowering the amount of greenhouse gases.

No one is expecting America to go 100 percent vegan ever, but a meaningful decrease in beef consumption would make a huge difference. Extrapolate this hypothetical 4-5 percent drop in demand for beef around the world, and the impact gets even bigger.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Let’s do some math

A 2021 report from the United Nations estimates that rewilding 350 million hectares of degraded terrestrial and aquatic habitats could generate $9 trillion in ecosystem services and remove 26 gigatons of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. This potential GHG reduction number is slightly less than the 33 gigatons of carbon dioxide emitted by the world in 2019. In essence, rewilding 350 million hectares would help lock away about one year of global emissions.

One acre is about 0.4 hectares. So, if you start with the 1.9 billion acres in the lower 48 in the United States, then take 41 percent of that currently being used for livestock production, you end up with about 780 million acres in the United States used to raise livestock.

In our hypothetical example of a 10 percent decline in beef demand, you get about 78 million acres freed up that can then be rewilded. Multiply 78 million by 0.4 to convert to hectares, and this gets you to about 32 hectares, or just under 10 percent of the 350 million acres needed to rewild and remove about one year’s worth of greenhouse gases.

Rewilding isn’t just taking something away

Now that I’ve angered people by taking away 10 percent of their hamburgers, let me highlight an example of rewilding that was wildly successful and doesn’t involve taking anything away.

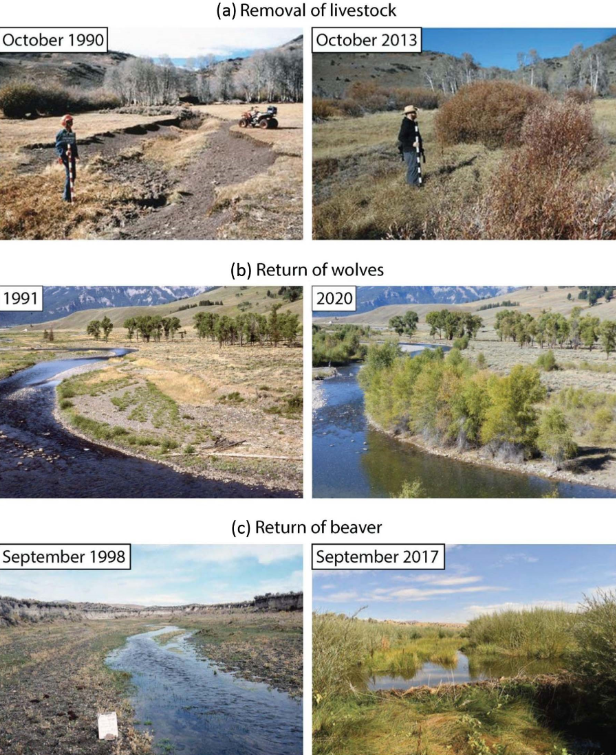

In 1995, gray wolves were reintroduced into Yellowstone National Park. The positive impacts were many. The wolves brought the overpopulation of deer and elk in the park under control. This cut down on overgrazing that the deer and the elk had been enjoying due to a lack of natural predators in the park. A deer and elk population held in check allowed willow and aspen trees to return to the landscape, which stabilized the riverbanks in the park, allowing river ecosystems to recover.

If companies add their expertise and capital to projects that protect resources that company needs, rewilding could get a monumental shot in the arm.

That’s a pretty good result, unless of course you were a deer or an elk. Ranchers around Yellowstone were some of the loudest voices in opposition to the reintroduction. But those fears of wolf predation of livestock have not come to pass, as the rate of predation of livestock by wolves has remained very low.

What is being done? What can be done?

Governments around the world are jumping on the rewilding bandwagon. Projects in Chile and Scotland are already being planned to rewild 300,000 and 200,000 hectares, respectively. These projects will roll out over a long time, with the Scottish plan stretched out over 30 years. But if similar plans are undertaken in enough countries, rewilding could make a significant impact on climate change and biodiversity challenges.

Alas, politics often gets in the way. A plan to rewild the American West by reintroducing wolves and beavers while lowering the cattle footprint across western public lands could cover tens of millions of acres but is opposed by many state legislatures in the American West. Cattle ranchers vote and can make campaign contributions. Wolves and beavers don’t vote and are quite ineffective at lobbying politicians.

Rewilding is not a new idea, but it is one just starting to get more attention as issues of biodiversity become more a part of the climate change conversation. Investors and companies that can find ways to support real and meaningful rewilding that is shown to address both biodiversity loss and climate change may be able to both improve their operations while getting a little goodwill from the public.

Most of the work done to date on rewilding has come from local and national governments in coordination with scientists and NGOS. If companies add their expertise and capital to projects that protect resources that company needs, rewilding could get a monumental shot in the arm. Historically, such support is done through charitable foundations connected to companies or company founders. If companies can make the business case for rewilding, humanity and shareholders could both benefit.

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Automotive / EVs, Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- BlockOffsets. Modernizing Environmental Offset Ownership. Access Here.

- Source: https://www.greenbiz.com/article/rewilding-us-could-be-powerful-tool-addressing-climate-change

- :has

- :is

- :not

- $UP

- 000

- 1

- 10

- 100

- 15%

- 200

- 2019

- 26

- 30

- 300

- 32

- 33

- 60

- 7

- 9

- a

- Able

- About

- Accounts

- acres

- across

- add

- address

- addressing

- Agricultural

- aim

- AIR

- All

- allow

- allowed

- Allowing

- already

- also

- Amazon

- america

- American

- amount

- an

- and

- animal

- anything

- ARE

- argument

- ARM

- around

- AS

- At

- Atmosphere

- attention

- automatically

- away

- back

- BE

- because

- become

- Beef

- been

- being

- benefit

- Big

- bigger

- Billion

- Bit

- Bloomberg

- both

- brought

- business

- businesses

- but

- by

- Calls

- Campaign

- CAN

- capital

- carbon

- carbon dioxide

- Carbon Sequestration

- care

- case

- Center

- challenges

- change

- changing

- check

- chemical

- Chile

- Clearing

- click

- Climate

- Climate change

- Colorado

- come

- Companies

- company

- concept

- connected

- Consider

- consume

- consumption

- contributions

- contributor

- control

- Conversation

- convert

- coordination

- could

- countries

- course

- cover

- critical

- crops

- Currently

- Cut

- damage

- data

- Date

- decade

- Decline

- decrease

- Deer

- Demand

- difference

- different

- directly

- do

- documented

- Doesn’t

- done

- Dont

- down

- dozens

- Drop

- due

- eat

- ecosystem

- Ecosystems

- Emissions

- end

- enough

- Environment

- environmental

- especially

- essence

- essential

- essential services

- essentially

- estimates

- Even

- EVER

- Every

- example

- expecting

- experiment

- expertise

- fears

- feeding

- Find

- five

- food

- Footprint

- For

- Foundations

- founders

- Free

- from

- Fuel

- GAS

- generate

- get

- getting

- GHG

- Global

- Go

- good

- Goodwill

- Governments

- greenhouse gas

- Greenhouse gas emissions

- had

- Have

- healthier

- Held

- help

- here

- Highlight

- historically

- How

- http

- HTTPS

- huge

- human

- Humanity

- Humans

- Humor

- i

- idea

- if

- Impact

- Impacts

- improve

- in

- In other

- indirectly

- inefficient

- intervention

- into

- Investors

- involve

- issues

- IT

- ITS

- just

- Lack

- Land

- lands

- landscape

- less

- letting

- Life

- little

- lobbying

- local

- Long

- long time

- loss

- Lot

- lower

- lowering

- major

- make

- Making

- many

- May..

- me

- mean

- meaningful

- methane

- million

- millions

- monumental

- more

- move

- myriad

- National

- Natural

- Nature

- nearly

- needed

- needs

- New

- next

- NGOs

- number

- of

- off

- often

- on

- ONE

- only

- Operations

- opposed

- opposition

- or

- Other

- our

- out

- over

- own

- Park

- part

- particularly

- pass

- People

- percent

- Place

- plan

- planned

- plans

- plato

- Plato Data Intelligence

- PlatoData

- Politicians

- politics

- Pollution

- population

- positive

- potential

- potentially

- powerful

- predators

- presentation

- pretty

- Prevention

- Problem

- Production

- projects

- protect

- provide

- providing

- public

- Putting

- quality

- raise

- Rate

- real

- Recharge

- Recover

- reduction

- remained

- remove

- removing

- report

- requires

- Resources

- respectively

- restoration

- result

- Results

- return

- River

- Roll

- Run

- s

- sake

- say

- ScienceAlert

- scientists

- sequestration

- serve

- Services

- serving

- Shareholders

- shot

- shown

- significant

- similar

- So

- soil

- some

- something

- start

- Starting

- State

- States

- Step

- Story

- stress

- successful

- such

- support

- tackling

- Take

- taking

- tens

- terrestrial

- than

- that

- The

- The Landscape

- the world

- their

- Them

- then

- These

- this

- those

- thought

- Through

- time

- to

- tool

- Total

- Trees

- Trillion

- two

- u.s.

- ultimate

- Ultimately

- under

- United

- United States

- use

- used

- uses

- very

- VOICES

- Vote

- was

- Water

- Way..

- ways

- we

- WELL

- were

- West

- Western

- What

- which

- while

- will

- with

- Wolf

- Work

- world

- world’s

- worth

- would

- year

- years

- you

- zephyrnet