Image from here

” data-medium-file=”https://platoaistream.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/ipo-rejects-janssens-secondary-patent-application-for-the-fumarate-salt-form-of-bedaquiline-1.jpg” data-large-file=”https://platoaistream.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/ipo-rejects-janssens-secondary-patent-application-for-the-fumarate-salt-form-of-bedaquiline.jpg” decoding=”async” width=”834″ height=”359″ src=”https://platoaistream.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/ipo-rejects-janssens-secondary-patent-application-for-the-fumarate-salt-form-of-bedaquiline.jpg” alt class=”wp-image-38440″ srcset=”https://platoaistream.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/ipo-rejects-janssens-secondary-patent-application-for-the-fumarate-salt-form-of-bedaquiline.jpg 834w, https://platoaistream.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/ipo-rejects-janssens-secondary-patent-application-for-the-fumarate-salt-form-of-bedaquiline-1.jpg 230w, https://platoaistream.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/ipo-rejects-janssens-secondary-patent-application-for-the-fumarate-salt-form-of-bedaquiline-2.jpg 768w, https://spicyip.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/sirturo-03-600×258.jpeg 600w” sizes=”(max-width: 834px) 100vw, 834px”>

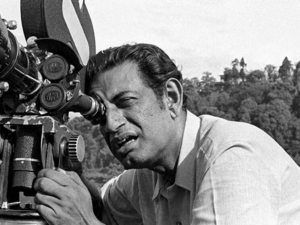

As many of our readers would know, recently the Patent Office rejected Janssen’s patent application for a treatment of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis drug treatment on the grounds that it failed to cross various patentability thresholds. The rejection was significant for several reasons: Naturally it is significant for access to medicines in a country where tuberculosis is regularly one of the biggest cause of health concerns. And on the more legal side, it highlighted the importance of pre-grant oppositions as the oppositions here could be seen to have significantly contributed to the patents office’s reasoning in rejecting the application. In the midst of various evidence-less discussions on patent oppositions (here), a headlining case like this one is an apt counter-narration that re-emphasises how pre-grants can contribute to a robust patent culture in the country where only inventions that actually cross the required thresholds are permitted patent protection. We’re very happy to bring our readers a detailed breakdown of the case in this guest post by Priyam Cherian and Roshan John. Priyam Cherian is an advocate and represented the second opponents before the Indian Patent Office. Roshan John is a lawyer and works on intellectual property issues in medicines. Views expressed are personal.

You can view our older posts around Bedaquiline here.

IPO Rejects Janssen’s Secondary Patent Application for the Fumarate Salt form of Bedaquiline

Priyam Cherian and Roshan John

On 23 March 2023, the Indian Patent Office (IPO) rejected (pdf) a secondary patent application on the fumarate salt form of Bedaquiline filed by Janssen, a part of pharmaceutical company Johnson & Johnson (J&J). Bedaquiline is a core drug for the treatment of drug resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB). DR-TB has posed significant public health challenges for decades.

Presently, Janssen has a patent on the base compound of Bedaquiline until July 2023 and as a result is the sole supplier of the medicine. This also means generic manufacturers cannot produce the medicine at least until 2023. Janssen has alsofiled multiple secondary patents in India around Bedaquiline other than the primary patent, including on method of use and processes. One of them was the secondary patent application on the fumarate salt of Bedaquiline, which could have potentially extended J&J’s monopoly until December 2027, thereby blocking Indian generic manufacturers from entering the supply chain with affordable generic versions for four more years. This secondary patent application was rejected by the patent office.

This post shall discuss the order of the Controller leading to the rejection of the patent application.

Background of the fumarate salt patent application

The fumarate salt patent application was filed by Janssen in India as a PCT national phase application no. 1220/MUMNP/2009 in June 2009. The PCT application originally filed had 21 claims, which were amended voluntarily to 22 claims. The originally filed claims were for the salt form of Bedaquiline. The application was published in August 2009 and a request for examination of the application was filed by the applicant in April 2010.

Of the claims thus amended:

- Claims 1-3 were related to fumarate salt of certain identified compounds (including Bedaquiline);

- Claims 4-5 were dependent claims;

- Claims 6-15 were related to composition;

- Claims 16-22 were dependent claims.

A first examination report (FER) was issued in March 2012 (pdf) which cited claims lacking an inventive step, not being patentable under Section 3(d) and not being invention within the meaning of Section 2(1)(j). The FER also raised objections related to amendment of the claims citing that they were not in the form of explanation, correction or disclaimer. In order to overcome the objections raised in the FER, Janssen modified its claims for a second time in January 2013 to cover a composition of bedaquiline fumarate and a wetting agent. Claims 2-5 and 16-21 of the originally filed claims were deleted, bringing the total number of claims to 7 (with only claim 1 as the independent claim). The claims had now moved from a salt compound as originally filed to a composition. This amendment strategy is routinely used (PDF, page 26) to bypass objections, like Section 3(d)—a provision that checks evergreening, on patentability.

Timelines and Pre-grant oppositions

A pre-grant opposition can be filed by any person after a patent application has been published and before a patent has been granted on various grounds under Section 25(1) of the Patents Act. Many of the irregular grants by the Patent Office could be attributed to information asymmetry. The primary objective of the pre-grant opposition is to aid the IPO in making decisions with respect to the grant or refusal of a patent application.

In the present case, two pre-grant oppositions were filed against the grant of the patent application—first by a patient group (pdf) and second by two Tuberculosis (TB) survivors (pdf). Both the oppositions supplemented information over and above the prior art documents cited in FER to aid the controller to examine the patent application.

In March 2013, the amended set of (7) claims was first opposed by the Network of Maharashtra People Living with HIV (NMP+), on grounds of prior claiming, invention known publicly, lack of inventive step, failure to disclose information related to foreign filing, and Section 3(d) [Section 25(1)(b), 25(1)(c), 25(1)(d), 25(1)(e), 25(1)(f) and 25(1)(h)]]. The applicant responded to the opposition in September 2013. Both the parties requested for a hearing before a decision was passed on the patent application. As per the docket, a hearing was scheduled for 15 October 2018, where NMP+ sought an adjournment.

Meanwhile in February 2019, a second opposition was filed by Nandita Venkatesan and Phumeza Tisile, two TB survivors against the grant of the patent application. The second opposition brought in more prior art to oppose the patent application for lack of inventive step and also highlighted serious concerns about the quality of the alleged invention. It also raised grounds of Section 3(d), Section 3(e), lack of novelty, failure to supply information required under Section 8 and broad nature of the claims [section 25(1)(b), 25(1)(e), 25(1)(f), 25(1)(g), 25(1)(h)]. The second opposition highlighted that the salt form application had several portions which were a verbatim copy of Janssen’s earlier patent application on rilpivirine (WO2006024667). It is the basic tenet of patent law that inventions, once disclosed, enter the public domain and hence do not merit a patent a second time.

On the issue of lack of inventive step, both the oppositions provided prior art documents distinct from those cited in the FER. Both the oppositions relied on different prior art documents to establish their case and aid the examination process.

The second opponents enquired about the status of their opposition in November 2020. Subsequently, the Controller issued a hearing notice for May 2022, wherein an adjournment was requested by the second opponents. A new hearing date was set for June 2022, which was adjourned to 18 November 2022 after a request from the patent applicant. A hearing notice was issued on 24 August 2022, which indicated pending objections related to Section 2(1)(ja), Section 3(d), Section 3(e) and the broad nature of the claims. The first hearing in the matter was finally held on 18 November 2022, and the Controller also provided two more subsequent hearings in November 2022. After these hearings, the Applicant made further amendments to their claims bringing down the total number claims from seven to five. In the interest of justice, the Controller provided a hearing to all the parties (opponents and applicant) on the amended claims in January 2023. The applicant further filed an amended and fine-tuned version of the claims based on the hearing and written submissions in January 2023.

Grounds of rejection

The claims of the application were found to be obvious, and not meeting the requirements of Section 3(d) and 3(e) of the Patents Act.

The complete specification identified fumarate salt of Bedaquiline in composition as an invention, citing the salt form’s non-hygroscopic nature and stability. The complete specification indicated that such characteristics of the salt form increased the bioavailability of the composition. However, during the course of the prosecution of the application, the applicant appeared to change the goalpost of the inventive step, by submitting that it was addition of TWEEN 20 (a wetting agent) to the composition that resulted in enhanced bioavailability of the claimed composition.

The order noted that the complete specification and the inventor’s affidavit on bioavailability of the composition nowhere indicated that the increased bioavailability resulted from addition of TWEEN20 to the composition. Rather the two documents indicated increased bioavailability of the composition on use of fumarate salt of Bedaquiline. Thus, the order held that the intent of the application was to protect fumarate salt of Bedaquiline and a composition comprising the same. The issue of lack of inventive step was therefore examined vis-a-vis use of fumarate salt of Bedaquiline in a composition.

The Controller found four prior art documents relevant for the purposes of the examining inventive step. Three of these documents were prior patent applications of Janssen itself. In fact, of the four prior art documents found to be relevant three were introduced by the two oppositions.

The order noted that prior art documents suggested composition of fumarate salt of Bedaquiline. Further, it noted that increased bioavailability of base by use of salt form was known. It was found that the application verbatim copied several portions and a claim of Janssen’s earlier application relating to use of wetting agent and its specific concentration in a composition. In absence of any suggestion in the complete specification on the specific advantage of adding the wetting agent, it was held that it would be obvious for a person skilled in the art to arrive at the invention by combining the teachings of the prior art. Thus the claims of the application were found to lack an inventive step.

With the change in the applicant’s stand on the inventive step of the invention being the use of a wetting agent in the composition, the requirement of Section 3(d) would be met only if it was shown that the said wetting agent enhanced the therapeutic efficacy of the known composition of fumarate salt of Bedaquiline. While the applicant claimed that use of wetting agent resulted in increased bioavailability of the composition, it was not shown whether such increased bioavailability resulted in enhancement of the known efficacy of the composition of fumarate Bedaquiline on the treatment of a patient. The claimed composition was thus found to be not patentable under Section 3(d) of the Act.

Further, it was held that the claimed composition resulted in aggregation of the properties of the components. In absence of any evidence related to the synergistic effect of the claimed composition, the same was held to be not patentable under Section 3(e) of the Act.

Theoretically, if an application, on the face of it, can be rejected under Section 3(d), there is no point in going further to analyse whether the invention is novel, non-obvious, and capable of industrial application. Regardless, it is important that the patent controller takes note of the invention failing to make the “inventive leap” from the prior art available while refusing a patent application (which is the norm at the IPO).

The controller’s succinct analysis on inventive step will help build the jurisprudence around obviousness so as to prevent the grant of patents on ‘inventions’ that do not merit them. In the present matter, the Controller has rightly noted, while analysing the inventive step in the application, that the complete specification did not show how the claimed composition had any surprising effect over the known composition of Bedaquiline. Thus, even if the applicant uses ‘smart’ legal arguments or amendments to evade Section 3(d) (which was also done in the present matter) and gets over exceptions to patentability, they could be put to test under conditions of patentability.

Transparency and efficiency

The Section 8 objection [S.25(1)(h)] for the applicant’s failure to disclose information regarding foreign applications did not withstand. However, it was only after the opponents pointed out that the patent applicant had failed to provide an updated status of their foreign application that the applicant provided those details, which indicated that the corresponding application was rejected in Argentina and Brazil (appealed).

Regular and timely updates and change in status of corresponding foreign application will help the patent office to better examine a similar patent application in a different country. This information under section 8 reduces the information asymmetry at the patent office and increases transparency.

It is also interesting to note that while the patent application for the base form of Bedaquiline (the primary patent) and other related applications were filed with the Delhi patent office, the salt form was filed with the Mumbai Patent Office (maybe for various reasons). There is a scope for streamlining of docketing similar applications to the same examiner/controller to facilitate faster disposal of applications and optimize the time of the Patent Office.

Conclusion

The present order of the Controller found three prior art documents filed by the opponents to be relevant to determine whether the claimed invention had an inventive step. At a time when there are discussions going on to gut the pre-grant opposition system in India, the present case is a great example on how pre-grant oppositions aid the controller in ensuring grant of quality patents. In the absence of a robust pre-grant opposition mechanism, it would have been impossible for people (against whom patents are granted) to bring any new information found at a later stage to help the controller grant quality patents.

After the news of rejection of the patent application, it was reported that at least two Indian manufacturers are ready to bring out generic versions of Bedaquiline by the expiry of the primary patent in July 2023. J&J in response to the rejection of the patent said that the ‘formulation patent’ (i.e. fumarate salt composition patent) would not prevent generic manufacturers from developing the API in their own formulations after the expiry of primary patent. If that is the case, J&J should withdraw or commit to not enforce its secondary patent on the fumarate salt especially in high TB burden countries, where it is pending or granted.

Having said that, the Controller’s order rejecting the patent application on fumarate salt of bedaquiline reflects the true spirit of Indian patent law by not allowing separate patents on routine changes to the same medicine. To supplement the efforts of providing affordable medicines, it is necessary to ensure that evergreening practices are taken seriously and measures are taken to prevent them.

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- Platoblockchain. Web3 Metaverse Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- Minting the Future w Adryenn Ashley. Access Here.

- Source: https://spicyip.com/2023/04/ipo-rejects-janssens-secondary-patent-application-for-the-fumarate-salt-form-of-bedaquiline.html

- :is

- 1

- 2012

- 2018

- 2019

- 2020

- 2022

- 2023

- 7

- 8

- a

- About

- above

- access

- Act

- actually

- addition

- ADvantage

- advocate

- affordable

- After

- against

- Agent

- aggregation

- Aid

- All

- alleged

- Allowing

- amendments

- analyse

- analysis

- and

- api

- appeared

- Application

- applications

- April

- APT

- ARE

- Argentina

- arguments

- around

- Art

- AS

- At

- AUGUST

- available

- base

- based

- basic

- BE

- before

- being

- Better

- Biggest

- blocking

- Brazil

- Breakdown

- bring

- Bringing

- broad

- brought

- build

- burden

- by

- CAN

- cannot

- capable

- case

- Cause

- certain

- chain

- challenges

- change

- Changes

- characteristics

- Checks

- cited

- claim

- claimed

- claiming

- claims

- combining

- commit

- company

- complete

- components

- Compound

- concentration

- Concerns

- conditions

- contribute

- contributed

- controller

- Core

- Corresponding

- could

- countries

- country

- course

- cover

- Cross

- Culture

- Date

- decades

- decision

- decisions

- Delhi

- dependent

- detailed

- details

- Determine

- developing

- DID

- different

- Disclose

- discuss

- discussions

- distinct

- documents

- domain

- down

- drug

- Drugs

- during

- e

- Earlier

- effect

- efforts

- enhanced

- enhancement

- ensure

- ensuring

- Enter

- especially

- establish

- Ether (ETH)

- Even

- evidence

- Examining

- example

- expiry

- explanation

- expressed

- Face

- facilitate

- Failed

- Failure

- faster

- February

- Filing

- Finally

- First

- For

- foreign

- form

- found

- from

- further

- going

- grant

- granted

- grants

- great

- Group

- Guest

- Guest Post

- happy

- Have

- headlining

- Health

- hearing

- Held

- help

- here

- High

- Highlighted

- HIV

- How

- However

- HTML

- HTTPS

- i

- identified

- importance

- important

- impossible

- in

- Including

- increased

- Increases

- independent

- india

- Indian

- indicated

- industrial

- information

- intellectual

- intellectual property

- intent

- interest

- introduced

- Invention

- inventions

- IPO

- issue

- Issued

- issues

- IT

- ITS

- itself

- January

- John

- Johnson

- July

- Justice

- Know

- known

- Lack

- Law

- lawyer

- leading

- Legal

- like

- living

- made

- make

- Making

- Manufacturers

- many

- March

- Matter

- max-width

- May..

- meaning

- means

- measures

- mechanism

- medicine

- meeting

- Merit

- method

- modified

- more

- multiple

- Mumbai

- National

- Nature

- necessary

- network

- New

- news

- noted

- novel

- novelty

- November

- number

- objective

- obvious

- october

- of

- Office

- on

- ONE

- opponents

- opposed

- opposition

- Optimize

- order

- originally

- Other

- Overcome

- own

- page

- part

- parties

- passed

- patent

- Patents

- patient

- pending

- People

- person

- personal

- Pharmaceutical

- phase

- plato

- Plato Data Intelligence

- PlatoData

- Point

- Post

- Posts

- potentially

- practices

- present

- prevent

- primary

- Prior

- process

- processes

- produce

- properties

- property

- PROSECUTION

- protect

- protection

- provide

- provided

- providing

- provision

- public

- public health

- publicly

- published

- purposes

- put

- quality

- raised

- rather

- readers

- ready

- reasons

- recently

- reduces

- reflects

- refusing

- regarding

- Regardless

- regularly

- related

- relevant

- report

- represented

- request

- requested

- required

- requirement

- Requirements

- resistant

- respect

- result

- robust

- routinely

- s

- Said

- salt

- same

- scheduled

- scope

- Second

- secondary

- Section

- separate

- September

- serious

- set

- seven

- several

- should

- show

- shown

- significant

- significantly

- similar

- skilled

- So

- specific

- specification

- spirit

- Stability

- Stage

- stand

- Status

- Step

- streamlining

- Submissions

- subsequent

- Subsequently

- such

- supplement

- supply

- supply chain

- surprising

- system

- takes

- test

- that

- The

- the information

- their

- Them

- Therapeutic

- thereby

- therefore

- These

- three

- time

- to

- Total

- Transparency

- treatment

- true

- under

- updated

- Updates

- use

- various

- version

- View

- views

- voluntarily

- whether

- which

- while

- will

- with

- withdraw

- within

- works

- would

- written

- years

- zephyrnet

![Webinar on “How Patent Monopolies on Biologics and Vaccines Work” [November 22]](https://platoaistream.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/webinar-on-how-patent-monopolies-on-biologics-and-vaccines-work-november-22-212x300.jpg)