On a drizzly February afternoon, I arrive at a modest, three-story building a stone’s throw from Kyoto’s Kamo River. A plaque reads “PLAYING CARDS” in gold letters against a staid shade of dark green, next to a stylish double door flanked by a pair of bright-red flags. Around the entrance, the pale brick facade has a distinctive mix of 1930s-style art deco curves and linear graphic stonework; it’s clear that in this quiet, largely residential area, this establishment isn’t like its neighbors. A pair of tourists and their Japanese guide coast along on bicycles. “This is the original headquarters of the video game company Nintendo,” the guide says in English as they slow down next to me. His clients express delight — they’d never have known if he hadn’t pointed it out.

I’ve come to visit the Marufukuro, an 18-room luxury hotel housed in the former Nintendo offices that once included the apartment home of the company’s founding Yamauchi family. It opened in April 2022 after a careful renovation by Plan Do See, a well-established Japanese hospitality firm that specializes in wedding venues and historically significant projects; after winning the bid for the project, Plan Do See got iconic architect Tadao Ando to design the hotel, and the top-tier Marufukuro suite — where guests can observe Ando’s hand-signed autograph in pencil on part of a wall — can go for over $1,300 a night.

The Marufukuro, despite being the birthplace of Nintendo, has no current relationship with the company — I’m repeatedly reminded about the importance of this distinction, which is funny, because Nintendo history is the main reason I was drawn here in the first place. The Yamauchi family sold its Nintendo shares back in 2014. The hotel is now owned by the No. 10 Family Office — a company created by Banjo Yamauchi in 2020 to reportedly “preserve the ‘unique creativity and pioneering mindset’ of [Nintendo’s third president] Hiroshi Yamauchi, who died in 2013, [and] to help Japan innovate.” Banjo is the biological grandson (and adopted son) of Hiroshi Yamauchi; the latter was responsible for Nintendo’s shift to video games, including its early work with experimental toys. After Hiroshi’s death, then-21-year-old Banjo received an “enormous inheritance.” By all appearances, No. 10 doesn’t have anything to do with game development — it’s an investment firm that oversaw a fortune of over 100 billion yen in 2021; family offices are typically set up to handle investments and wealth management for ultra-rich “high net worth” families, often with a focus on dynastic responsibilities. The hotel name comes from another Yamauchi card company, Marufuku, with the -ro added to denote a luxury building, and Plan Do See runs the hotel operations.

“Since 1889, [Nintendo] have been keeping the same attitude of pushing boundaries, even though they had faced management crisis and the threat of bankruptcy several times in their history,” says Banjo Yamauchi via email. “This building represents [the] tough history of Nintendo.” According to Yamauchi, the idea to convert the building was mainly for historical preservation, and many of its original architectural features, like its Showa-era-style roof, have been kept. To the north is the oldest building, where I’ll be staying for the next three nights. It began 100 years ago as a warehouse before three more additions were made, including the new Ando annex. My section of the hotel is a three-floor walkup with an old-school non-functional cage-style elevator; my red-carpeted room is large and airy with a high, partly vaulted ceiling and a checkerboard-tile balcony overlooking the river. I am delighted for the first time in years to receive a large old brass key, rather than an electronic room card. On my second morning there, I wake to a light dusting of snow.

In 1959, the company moved to a bigger location, and the whole compound sat unused and empty. Iku Hasegawa, who works at the hotel and represents Plan Do See, explains that most of the buildings were already well preserved. “There was one worker from Nintendo who would come every month to open the windows and the doors to air everything out, and make sure everything was OK,” she explains. Patrick Okada, managing director of No. 10’s business incubation office, happens to be visiting the hotel with his family during my stay, and tells me later, via email, that Nintendo “fans” visited the building during its long vacant period, taking photos and leaving signatures.

Today, its guests are a mix of Japanese regional visitors and, more recently, since Japan lifted travel restrictions around November 2022, international arrivals like myself (and according to staff, a few from the American military base in Okinawa). Some are architecture buffs who come to see Ando’s work; others are foodies keen to visit the hotel restaurant, Carta, helmed by Japanese chef Ai Hosokawa. It is around Hosokawa’s very photogenic meals (all three are provided in the room rate per day) that I get to observe fellow guests in the communal dining room: several mother-and-daughter combos, young families, quiet couples, and a small, excited friend group. During my stay, I seem to be the only foreign guest.

In learning more about the neighborhood, I begin to suspect that the Marufukuro’s presence might be the beginning of a long-term plan. “They were able to beautify the area by cleaning the river around here,” Hasegawa says. “[Gojo] is a historical area, so they wanted to make it more beautiful and for more people, especially artists, to come here.” I am told that the (very good) coffee shop around the corner, murmur coffee, occupies a building owned by one of the Yamauchi daughters (it also provides the hotel with its own Marufuku roast, stocked in each guest room). According to Hasegawa, the Marufukuro’s revitalization went hand in hand with encouraging creative interest in the neighborhood; wandering around the area yields no real sign of this intended outcome, at least not yet, given that half of the hotel’s existence has taken place under pandemic restrictions. If the Marufukuro is meant to function as a sort of historical and cultural beacon, it’s doing so in a sphere where it already has real estate influence; besides the storied past of the physical buildings, it is a business that leans toward the history and influence of the Yamauchi family more so than the modern video game company we know today.

The most visibly game-related space in the hotel is its small library, curated by Banjo Yamauchi with help from Japanese book company Bach; there’s also an interactive “toy library” by artist Daito Manabe and an installation by Rhizomatiks, a creative collective that has worked on game-like projects with ex-Sega legend Tetsuya Mizuguchi. This is the only part of the hotel directly operated by the No. 10 office, and only hotel guests are allowed to use it. I was half hoping for a special archive, but this isn’t that sort of library. It’s more of an elegant reading lounge with a reflective “infinity” ceiling, inspired by Yamauchi’s love of the film Interstellar; there’s a bar where guests are welcome to make their own drinks, reinforcing the sense that we’re all in a very nice house rather than a hotel.

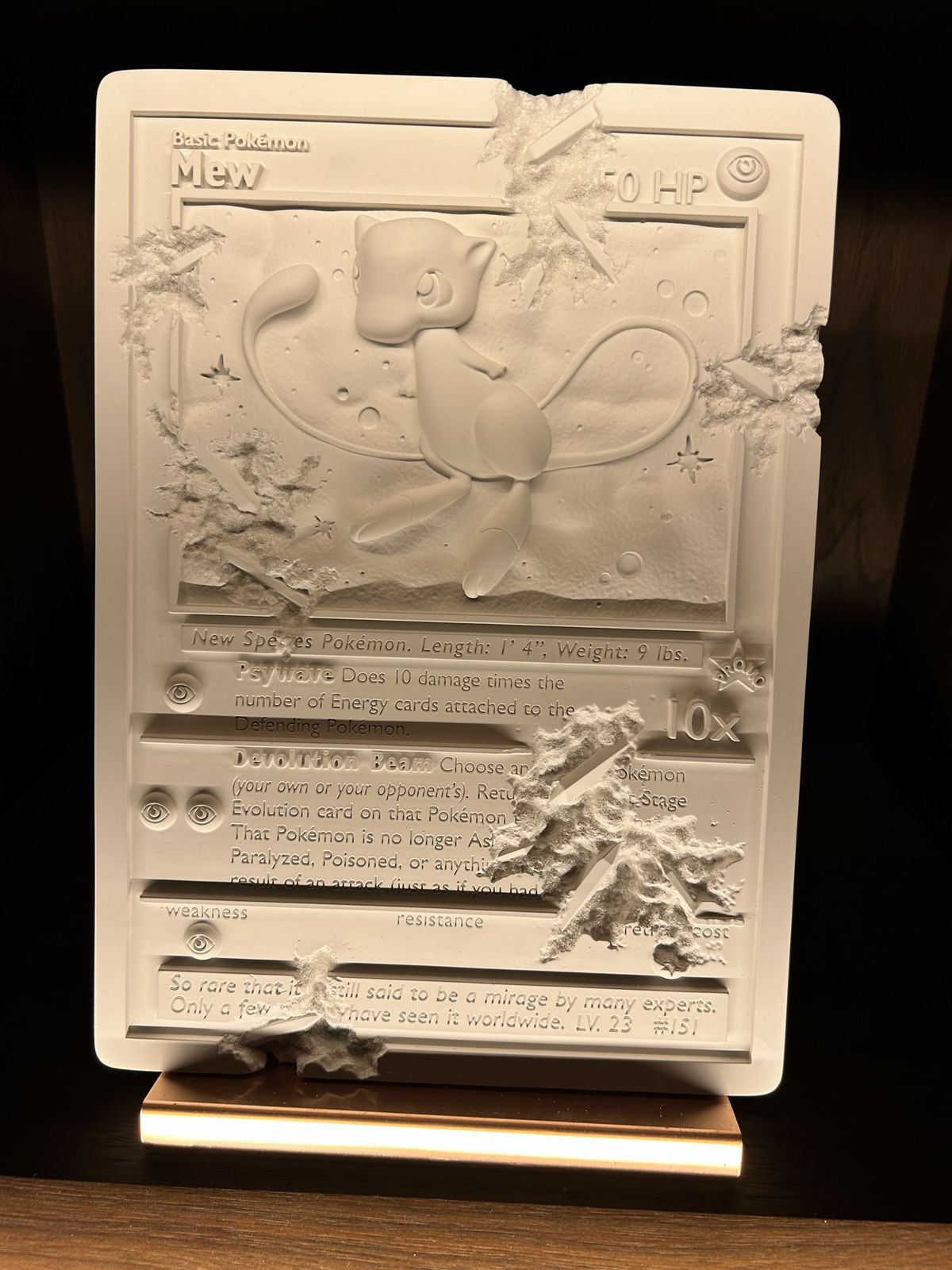

Unlike most libraries, the Marufukuro allows you to bring that expensive glass of whiskey into the library proper, to sit, read, and drink. It houses high-end design books that run the gamut from modernist art philosophy to Damien Hirst, interspersed with Nintendo-themed art objects commissioned by Yamauchi (think: a frosted glass Game Boy, or a Switch designed to look like an underwater relic covered in algae). There are a few historical Nintendo treats on display, like an original red-trimmed Famicom console and, to my excitement, a Light Telephone from 1971. The latter was a novelty gadget designed by Gunpei Yokoi to let people communicate through light sensors, and resembles an enormously clunky mega flashlight. I ask if we’re allowed to use the consoles on display, or if the hotel has an arsenal of Nintendo products that can be loaned to guests. Hasegawa explains that the hotel’s gaming consoles aren’t allowed in rooms, so as not to encourage gambling.

A handful of books are Nintendo-specific, including Osamu Inoue’s The Philosophy of Nintendo, and Erik Voskuil’s Before Mario, which documents obscure Nintendo toys. My favorite, though, was the companion book to the 2003 “Family Computer’’ exhibition at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum of Photography, filled with short essays, Famicom games, and interviews with Shigeru Miyamoto and copywriter Shigesato Itoi, who coined the phrase “no crying until the end” in Mother. (There’s also an interview with a young Hideo Kojima.)

My time at the Marufukuro — a pleasant luxuriation in excellent Japanese hospitality — was not the experience I’d envisioned when I’d first learned of its existence. As a vacation, it’s a niche historical landmark exuding warmth and luxury, and makes for a memorable splurge. It is easiest to describe it offhandedly as “the Nintendo hotel,” though there’s nothing outwardly Nintendo about it — more of a low-key look at the legacy of the Yamauchi family and its endeavors to use its resources to “return the inherited material and spiritual wealth to the public.” I think about the murmur coffee shop and wonder how much of the land and buildings around this neighborhood are owned by the Yamauchis. If the Marufukuro’s long-term goal is to breathe new life into the area without disrupting the residents, then openly invoking the Nintendo name would probably cultivate a louder, brasher sort of tourism that doesn’t really jibe with Plan Do See’s understated brand of hoteliering or No. 10’s purported goals of philanthropy and giving back to Japanese society.

The separation between No. 10 (and the Marufukuro) and Nintendo is understandable, since the Yamauchis sold off most of their shares in the latter nearly 10 years ago. But if there is a social responsibility angle to the former’s mission, it feels sadly in conflict with the latter’s longtime crackdowns on piracy and ROM emulation that have become bastions of game preservation in a precarious digital-only world. If No. 10 wants to adopt the Nintendo approach to innovation and excitement in its own projects, it will hopefully do so with the awareness that bringing new forms of socially minded creativity into the world should also include long-term plans to maintain these projects; in a modern context, it is impossible to discuss the impact and legacy of Nintendo — one of the most beloved entertainment brands in the world — without recognizing its failure to preserve its own work for current and future generations. Even while I’m constantly reminded that the Marufukuro and Nintendo are operationally disconnected entities, it’s hard to think of one without the other in a broader historical context — I leave wondering who will preserve Nintendo’s work in the same careful way.

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- PlatoHealth. Biotech and Clinical Trials Intelligence. Access Here.

- Source: https://www.polygon.com/24009383/nintendo-hotel-marufukuro-kyoto-gojo

- :has

- :is

- :not

- :where

- $UP

- 10

- 100

- 2013

- 2020

- 2022

- 300

- 50

- 70

- a

- Able

- About

- about IT

- According

- added

- additions

- adopt

- adopted

- After

- against

- ago

- AIR

- All

- allowed

- allows

- along

- already

- also

- am

- American

- an

- and

- Annex

- Another

- anything

- Apartment

- appearances

- approach

- April

- architectural

- architecture

- Archive

- ARE

- AREA

- around

- Arsenal

- Art

- art piece

- artist

- Artists

- AS

- ask

- At

- attitude

- Autograph

- awareness

- back

- Bankruptcy

- bar

- base

- BE

- beacon

- beautiful

- because

- become

- been

- before

- began

- begin

- Beginning

- being

- beloved

- besides

- between

- bicycles

- bid

- bigger

- Billion

- Bloomberg

- book

- Books

- boundaries

- brand

- brands

- brass

- BREATHE

- bring

- Bringing

- broader

- Building

- built

- business

- Business Incubation

- but

- by

- CAN

- card

- Cards

- careful

- ceiling

- Cleaning

- clear

- clients

- CO

- Coast

- Coffee

- coffee shop

- coined

- collection

- Collective

- COM

- combination

- come

- communal

- communicate

- companion

- company

- Company’s

- Compound

- conflict

- Console

- consoles

- constantly

- context

- convert

- Corner

- covered

- crackdowns

- created

- Creative

- creativity

- crisis

- Crying

- Cultivate

- cultural

- curated

- Current

- Damien Hirst

- Dark

- day

- Days

- Death

- delight

- delighted

- depicting

- describe

- Design

- designed

- Despite

- Development

- died

- dining

- directly

- Director

- disconnected

- discuss

- Display

- displayed

- distinction

- distinctive

- do

- documents

- Doesn’t

- doing

- Door

- doors

- double

- down

- drawn

- Drink

- drinks

- during

- each

- Early

- easiest

- Electronic

- empty

- encourage

- encouraging

- endeavors

- English

- enormously

- Entertainment

- entities

- entrance

- envisioned

- erik

- especially

- establishment

- estate

- Ether (ETH)

- Eurogamer

- Even

- Every

- everything

- excellent

- excited

- Excitement

- exhibition

- expensive

- experience

- experimental

- Explains

- express

- faced

- Failure

- families

- family

- family office

- Favorite

- Features

- February

- feels

- fellow

- few

- filled

- Film

- Firm

- First

- first time

- flags

- Focus

- For

- foreign

- Former

- forms

- Fortune

- founding

- friend

- from

- full

- function

- funny

- future

- Gambling

- game

- game-development

- Games

- gaming

- generations

- get

- given

- Giving

- glass

- Go

- goal

- Goals

- Gold

- good

- got

- graphic

- Green

- Group

- Guest

- guests

- guide

- had

- Half

- hand

- handful

- handle

- happens

- Hard

- Have

- he

- Headquarters

- helmed

- help

- here

- hideo kojima

- High

- High-End

- his

- historical

- historically

- history

- Home

- Hopefully

- hoping

- hospitality

- hotel

- House

- houses

- How

- hq

- HTML

- http

- HTTPS

- i

- I’LL

- iconic

- idea

- if

- Impact

- importance

- impossible

- in

- include

- included

- Including

- INCUBATION

- influence

- inheritance

- innovate

- Innovation

- inspired

- installation

- intended

- interactive

- interest

- International

- Interview

- Interviews

- into

- investment

- Investments

- Investopedia

- IT

- ITS

- Japan

- Japanese

- jpg

- Keen

- keeping

- kept

- Key

- Know

- known

- kojima

- Land

- landmark

- large

- largely

- later

- leading

- learned

- learning

- least

- Leave

- leaving

- Legacy

- let

- libraries

- Library

- Life

- Lifted

- light

- like

- Lobby

- location

- Long

- long-term

- Look

- look like

- louder

- Lounge

- love

- Luxury

- made

- Main

- mainly

- maintain

- make

- MAKES

- management

- managing

- Managing Director

- many

- Mario

- material

- me

- meals

- meant

- Mega

- memorable

- might

- Military

- minded

- Mission

- mix

- Modern

- modest

- Month

- more

- morning

- most

- moved

- much

- Museum

- my

- myself

- name

- nearly

- neighbors

- net

- never

- New

- next

- nice

- niche

- night

- Nintendo

- no

- North

- nothing

- novelty

- November

- now

- objects

- observe

- occupies

- of

- off

- Office

- offices

- often

- Old

- oldest

- on

- once

- ONE

- only

- open

- opened

- openly

- operated

- Operations

- or

- original

- Other

- Others

- out

- Outcome

- over

- own

- owned

- pair

- pandemic

- part

- past

- patrick

- People

- per

- period

- PHILANTHROPY

- philosophy

- photography

- Photos

- physical

- piece

- Pioneering

- Place

- plan

- plans

- plato

- Plato Data Intelligence

- PlatoData

- playing

- Polygon

- presence

- preservation

- preserved

- president

- probably

- Products

- project

- projects

- proper

- provided

- provides

- Pushing

- Rate

- rather

- Read

- Reading

- real

- real estate

- really

- reason

- receive

- received

- recently

- recognizing

- regional

- relationship

- REPEATEDLY

- represents

- resembles

- residential

- residents

- Resources

- responsibilities

- responsibility

- responsible

- restaurant

- restrictions

- Reuters

- River

- roof

- Room

- Rooms

- Run

- runs

- sadly

- same

- says

- Second

- Section

- see

- seem

- sense

- sensors

- set

- several

- Shares

- she

- shelves

- shift

- Shop

- Short

- shot

- should

- sign

- Signatures

- significant

- since

- sit

- slow

- small

- snow

- So

- Social

- socially

- Society

- sold

- some

- son

- Space

- special

- specializes

- spent

- Sponsored

- Staff

- stay

- staying

- suite

- sure

- Switch

- taken

- taking

- tells

- than

- that

- The

- The Area

- the world

- their

- then

- There.

- These

- they

- think

- Third

- this

- though?

- threat

- three

- Through

- time

- times

- to

- today

- tokyo

- told

- tough

- Tourism

- toward

- travel

- treats

- tripadvisor

- true

- typically

- under

- understandable

- underwater

- until

- unused

- use

- vacation

- venues

- very

- via

- Video

- video game

- video games

- vintage

- Visit

- visited

- visitors

- Wake

- Wall

- wanted

- wants

- Warehouse

- warmth

- was

- Way..

- we

- Wealth

- wealth management

- webp

- wedding

- welcome

- WELL

- went

- were

- when

- which

- while

- WHO

- whole

- will

- windows

- winning

- with

- without

- wonder

- wondering

- Work

- worker

- works

- world

- would

- years

- Yen

- yet

- yields

- you

- young

- youtube

- zephyrnet