Non-invasive low-frequency focused ultrasound (FUS), delivered in combination with intravenously administered microbubbles, can temporarily open the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and enable drugs that combat Alzheimer’s disease to enter the brain and reach their therapeutic targets. The combination of an amyloid-beta plaque-reducing drug followed by FUS is proving to be safe and more effective in reducing plaque deposits in the brain than drug therapy alone. While not curing Alzheimer’s disease, reduction of plaque can reduce the disease’s cognitive impact and slow its progression.

Initial findings from a small first-in-human clinical trial, performed at WVU Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute and reported in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), stimulate hope that this combined treatment may someday become standard of care. In fact, 60 Minutes, a popular CBS television news magazine, aired a lengthy profile of the pioneering research of neurosurgeon Ali Rezai earlier this month, which included an interview with one of the three participants in this Alzheimer’s clinical trial.

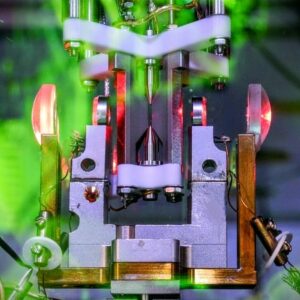

Rezai and colleagues are using a focused ultrasound device (the Exablate Model 4000 Type 2) to disrupt the BBB in patients, starting within two hours following intravenous infusion of aducanumab. Aducanumab and lecanemab (which will also be tested in the trial) are US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-cleared monoclonal antibody therapies that can reduce amyloid-beta plaques. However, the BBB impedes most of these antibodies from entering the brain.

The proof-of-concept clinical trial included three participants with mild Alzheimer’s disease. The objective was to evaluate the safety and feasibility of combining aducanumab with FUS to open the BBB and enhance drug delivery and amyloid removal.

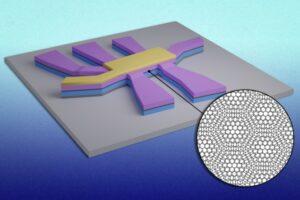

For the FUS procedure, patients were fitted with a hemispherical helmet containing 1024 independently controllable ultrasound sources. These sources emit ultrasound waves directed onto targets under real-time MRI guidance. During the sonications, a suspension of phospholipid-encapsulated perfluoropropane bubbles is infused intravenously. The team used scattered signals from these microbubbles to determine the appropriate acoustic power levels that will safely open the BBB.

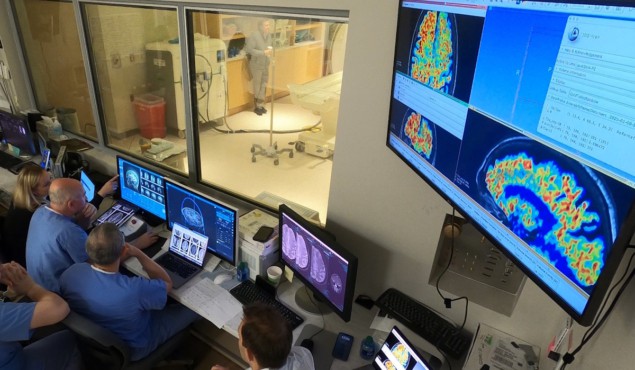

Upon completion of the FUS procedure, the researchers used T1-weighted MRI with gadolinium contrast enhancement to determine opening of the BBB in the targeted locations, repeated 24 and 48 h later to confirm that the BBB had closed. They also performed follow-up MRIs 30 days and one year after completion of the combined treatment.

Participants received six monthly treatments of intravenous aducanumab with dose escalation (from 1 mg/kg of body weight up to 6 mg/kg), followed by FUS. The researchers explain that in this phase of the clinical trial, they restricted FUS application to one brain hemisphere, in regions of the frontal lobe, temporal lobe or hippocampus with high levels of amyloid-beta plaque. Corresponding brain regions in the contralateral hemisphere that were not exposed to FUS served as controls. During the follow-up phase, patients received a monthly infusion of 10 mg/kg of aducanumab without FUS.

To quantify amyloid-beta levels, the team performed 18F-florbetaben PET scans at baseline, at three, 11 and 19 weeks during the treatment, and at 26 weeks and one year in the follow-up phase. Rezai reports that for all three patients, 18F-florbetabin PET scans showed that after 26 weeks, amyloid-beta plaques were reduced by an average of 32% (measured via the standardized uptake value ratio) in brain regions where the BBB had been opened, compared with corresponding regions in the untreated hemisphere.

The reduction in centiloid value, a scale used to standardize PET-based amyloid burden measurements, was 48%, 49% and 63% for the three participants, respectively. Rezai notes that the clinical trial did not quantify monoclonal antibody penetration because it was not designed for this purpose.

Patients are now being recruited for the second phase of the clinical trial, which will use lecanemab as the monoclonal antibody therapy. “We are limited by the FDA to treat up to 40 cc of the brain,” explains Rezai. “FUS will be administered only once a month for six months, comparable to the methods for aducanumab, with patient 1 BBB opening of up to 10 cc; then the following patients will have BBB opening up to 20 and 40 cc respectively.”

MR-guided focused ultrasound delivers antibody therapy directly into the brain

In the 60 Minutes interview, 61-year-old patient Dan Miller, whose wife first noticed behavioural changes four years previously, said that viewing the final MR images of his brain showing plaque reduction “was surreal”. He still exhibits occasional unusual behaviour, but there has been no further visible progression. Miller and his wife are hopeful for the future.

In an accompanying NEJM editorial, another pioneer in the clinical use of FUS, Kullervo Hynynen of Sunnybrook Research Institute in Toronto, notes that “expanding treatment to clinically significant volumes on both sides of the brain is crucial for assessing its efficacy in slowing disease progression. Additional studies are needed to establish long-term safety and efficacy, and cost-effective treatment devices that are not reliant on online MRI guidance must be developed for broader accessibility.”

But, like Miller, Hynynen is optimistic.

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- PlatoHealth. Biotech and Clinical Trials Intelligence. Access Here.

- Source: https://physicsworld.com/a/focused-ultrasound-plus-plaque-reducing-drugs-could-slow-alzheimers-progression/

- :has

- :is

- :not

- :where

- $UP

- 1

- 10

- 11

- 19

- 20

- 24

- 26

- 30

- 90

- a

- accessibility

- acoustic

- Additional

- administered

- administration

- After

- All

- alone

- also

- alzheimer

- Alzheimer’s

- amyloid

- an

- and

- Another

- Antibodies

- antibody

- Application

- appropriate

- ARE

- AREA

- AS

- Assessing

- At

- average

- barrier

- Baseline

- BE

- because

- become

- been

- behaviour

- being

- body

- both

- Both Sides

- Brain

- broader

- burden

- but

- by

- CAN

- care

- centre

- Changes

- click

- Clinical

- clinically

- closed

- cognitive

- colleagues

- combat

- combination

- combined

- combining

- comparable

- compared

- completion

- Confirm

- contrast

- control

- controls

- Corresponding

- cost-effective

- could

- crucial

- curing

- Days

- delivered

- delivers

- delivery

- deposits

- designed

- Determine

- developed

- device

- Devices

- DID

- directed

- directly

- Disease

- Disrupt

- dose

- drug

- Drug Delivery

- Drugs

- during

- Earlier

- Effective

- efficacy

- enable

- England

- enhance

- enhancement

- Enter

- entering

- escalation

- establish

- evaluate

- exhibits

- Explain

- Explains

- exposed

- fact

- fda

- feasibility

- final

- findings

- First

- focused

- followed

- following

- food

- Food and Drug Administration

- For

- four

- from

- further

- future

- guidance

- had

- Have

- he

- Health

- High

- his

- hope

- hopeful

- HOURS

- However

- HTTPS

- image

- images

- Impact

- in

- included

- independently

- information

- infused

- infusion

- Institute

- Interview

- into

- intravenous

- intravenously

- issue

- IT

- ITS

- journal

- jpg

- later

- levels

- like

- Limited

- locations

- long-term

- magazine

- max-width

- May..

- measured

- measurements

- methods

- mild

- Miller

- model

- Month

- monthly

- months

- more

- most

- mr

- MRI

- must

- needed

- Neuroscience

- news

- no

- Notes

- now

- objective

- occasional

- of

- on

- once

- ONE

- online

- only

- open

- opened

- opening

- Optimistic

- or

- participants

- patient

- patients

- penetration

- performed

- pet

- phase

- Physics

- Physics World

- pioneer

- Pioneering

- plan

- planning

- plato

- Plato Data Intelligence

- PlatoData

- plus

- Popular

- power

- previously

- procedure

- progression

- proving

- purpose

- ratio

- reach

- real-time

- received

- reduce

- Reduced

- reducing

- reduction

- regions

- removal

- repeated

- Reported

- Reports

- research

- researchers

- respectively

- restricted

- s

- safe

- safely

- Safety

- Said

- Scale

- scans

- scattered

- SCIENCES

- Second

- served

- showed

- showing

- shown

- Sides

- signals

- significant

- SIX

- Six months

- slow

- Slowing

- small

- someday

- Sources

- standard

- standardized

- Starting

- Still

- stimulate

- studies

- suspension

- targeted

- targets

- team

- television

- tested

- than

- that

- The

- The Future

- The West

- their

- then

- Therapeutic

- therapies

- therapy

- There.

- These

- they

- this

- three

- thumbnail

- to

- toronto

- treat

- treatment

- treatments

- trial

- true

- two

- type

- ultrasound

- under

- undergoes

- university

- unusual

- uptake

- us

- US Food

- use

- used

- using

- value

- via

- viewing

- virginia

- visible

- volumes

- was

- waves

- Weeks

- weight

- were

- West

- West Virginia

- which

- while

- whose

- wife

- will

- with

- within

- without

- world

- year

- years

- zephyrnet