The COVID pandemic wrought havoc on the production of semiconductor chips, in turn that shortage shook vehicle production and hobbled the global economy. However, at this point the worst of the shortage is behind us.

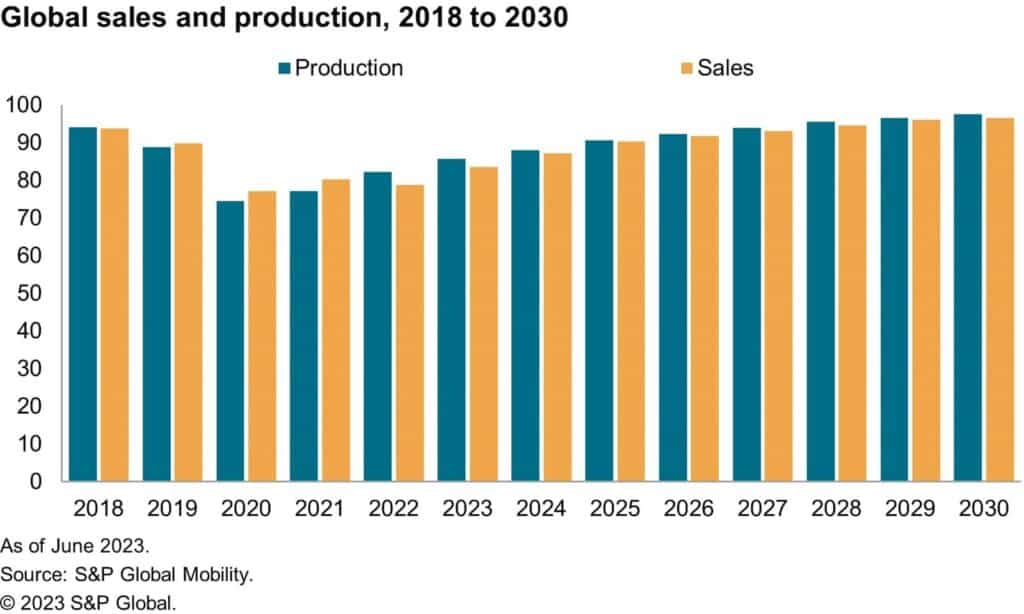

Production has been steady — and steadily increasing — and the supply of new cars for sale has recovered to at least a new normal. That’s the conclusion of a new report by S&P Global Mobility.

S&P analyzed automaker production figures against previously published production plans. Its report estimates more than 9.5 million units of global light-vehicle production were lost in 2021 as a direct result of the semiconductor shortage.

Another 3 million vehicles were not produced in 2022. Then in the first six months of 2023, production reduction because of the semiconductor shortage fell to about 524,000 vehicles globally. Although the supply of semiconductors remains constrained, more predictable availability has allowed automakers to adapt their production schedules.

Production in 2023 has increased as automakers and suppliers have adapted to the current environment, and 2023 sales are improving with more inventory. That said, the pre-pandemic momentum toward a 100-million global vehicle production year has been set back by a decade, according to S&P Global Mobility analysis.

Market adjustment

The echoes of the shortage and constrained new vehicle supply go far beyond simple production. The pandemic hastened a change in mindset among dealers and consumers. It’s an axiom of business that inventory is a burden to a retailer. Inventory represents capital invested that is sitting idle, waiting to be sold. It’s a necessary evil that a retailer must have stock to sell, but also has to pay for the stock and the space to sell it.

The pandemic-related shortages allowed retailers to shift towards an order fulfillment model with less stock on hand, and consumers had to get used to waiting for their new cars. That’s part of the new normal that reduces inventory costs for dealers, and scarcity also allowed them a bit more latitude to mark up prices on desirable models.

Yet the ability to adjust prices for scarcity did little for automaker profitability when there were fewer vehicles to sell. “Every 100,000 units of lost F-Series production costs Ford about $4.7 billion of revenue,” wrote Morningstar’s David Whiston in August 2021. “Given what we assume is an EBIT margin in the high teens to 20%, we calculate lost EBIT of about $937 million for every 100,000 lost U.S. F-Series wholesale units.”

The pandemic changed everything

Prior to the pandemic, the automotive industry would experience periodic semiconductor supply chain challenges, but those problems tended to be restricted to a single component type or individual supplier. What was unique about the pandemic period was the wholesale shortages among virtually all suppliers, impacting multiple component types.

“We’ve moved from obvious disruption, clearly visible at the automaker and plant level, to a stage where we know constraint remains, but it is impossible to identify,” said Mark Fulthorpe, S&P Global Mobility executive director of global light-vehicle production.

“We are now in a position where the auto industry has adapted to a constrained supply, and as a result is much less likely to be hit by significant disruption,” Fulthorpe added. “With the current semiconductor supply levels, we estimate that 22 million units of global light-vehicle production per quarter could be supported.”

However, industry demand for increasingly complex infotainment, advanced safety and vehicle autonomy systems will continue to escalate usage of semiconductors in vehicles. Phil Amsrud, senior principal analyst in the S&P Global Mobility supplier and components team, estimates that the value of semiconductors installed in vehicles averaged $500 per car in 2020, but is forecast to reach $1,400 per car by 2028.

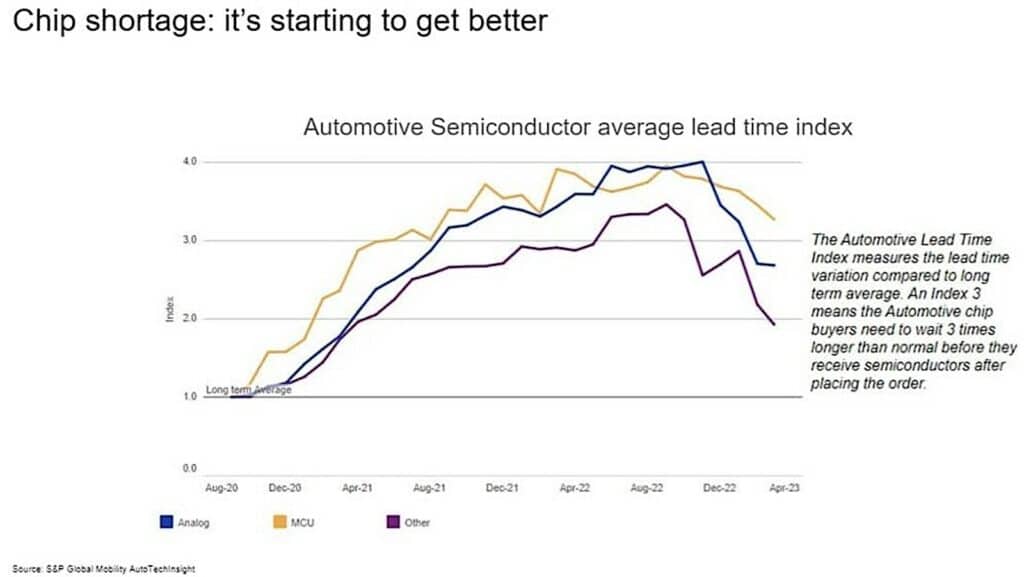

“Before the pandemic, the lead time from order to shipment of chips was three to four months. During the pandemic in 2021 and 2022, that wait grew to a year or longer,” Amsrud said. “But while other industries such as mobile phones and PCs have experienced cooling demand of late, automotive semiconductor demand is increasing, and some chip manufacturers have pivoted capacity to address that need.”

That said, the types of chips for automotive-grade use versus communications equipment often are not the same; or there are different qualification levels in automotive that complicate using consumer grade components in automotive applications, Amsrud noted.

A 10-year setback in production

Even though production and sales have rebounded to normal levels, that does nothing to make up for the lost opportunities during the pandemic. The early-2019 S&P Global Mobility forecast, which was issued prior to the pandemic, projected global sales and production to exceed 100 million units annually as soon as 2022.

That milestone is now not expected until 2030 or later, according to the new report. Consequently, the auto industry’s growth trajectory has been thrown off by roughly a decade compared with pre-pandemic expectations.

The June 2023 S&P Global Mobility forecast sees sales reaching 83.6 million units globally this year. The company now projects that it will be 2027 before the automotive industry sees a 93-million-unit year, and the prospect of 100 million units is not expected until 2030 at the earliest. Of course, that projection assumes no unforeseen events, such as a broader war in Europe or a second pandemic, that could disrupt the global economy.

As the report concludes, “Mid-2023 marks an inflection point when the semiconductor supply is no longer limiting vehicle production. There will continue to be parts of the supply chain that pose threats but those seem more episodic than systemic. From the automotive industry perspective, lessons learned from the pandemic shortages — especially the long-term balance of mature versus advanced process nodes — is critical. The industry may have survived the COVID semiconductor crisis, but that does not mean it is out of the woods.”

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Automotive / EVs, Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- BlockOffsets. Modernizing Environmental Offset Ownership. Access Here.

- Source: https://www.thedetroitbureau.com/2023/07/chip-shortage-largely-over-but-hangover-remains/

- :has

- :is

- :not

- :where

- ][p

- $UP

- 000

- 100

- 2020

- 2021

- 2022

- 2023

- 2028

- 2030

- 22

- 7

- 9

- a

- ability

- About

- According

- adapt

- adapted

- added

- address

- advanced

- against

- All

- allowed

- also

- Although

- among

- an

- analysis

- analyst

- analyzed

- and

- Annually

- applications

- ARE

- AS

- assume

- assumes

- At

- AUGUST

- auto

- automakers

- automotive

- automotive industry

- availability

- available

- back

- Balance

- BE

- because

- become

- been

- before

- behind

- Beyond

- Billion

- Bit

- burden

- Bureau

- business

- but

- by

- calculate

- Capacity

- capital

- car

- cars

- chain

- challenges

- change

- changed

- chip

- chip shortage

- Chips

- clearly

- Communications

- company

- compared

- complex

- component

- components

- conclusion

- Consequently

- consumer

- Consumers

- continue

- Costs

- could

- course

- Covid

- crisis

- critical

- Current

- David

- decade

- Demand

- DID

- different

- direct

- Director

- Disrupt

- Disruption

- does

- during

- echoes

- economy

- Environment

- equipment

- especially

- estimate

- estimates

- events

- Every

- exceed

- executive

- Executive Director

- expectations

- expected

- experience

- experienced

- far

- fewer

- Figures

- First

- For

- Ford

- Forecast

- four

- from

- fulfillment

- get

- Global

- Global economy

- Globally

- Go

- grade

- graph

- Growth

- had

- hand

- Have

- High

- higher

- Hit

- However

- HTTPS

- Hyundai

- identify

- Idle

- impacting

- impossible

- improving

- in

- increasing

- increasingly

- individual

- industries

- industry

- industry’s

- Inflection Point

- inventory

- invested

- Issued

- IT

- ITS

- jpg

- june

- Know

- largely

- Late

- later

- latitude

- lead

- learned

- least

- less

- Lessons

- Lessons Learned

- Level

- levels

- likely

- Line

- little

- long-term

- longer

- lost

- make

- Manufacturers

- Margin

- mark

- mature

- max-width

- May..

- mean

- milestone

- million

- Mindset

- Mobile

- mobile phones

- mobility

- Mode

- models

- Momentum

- months

- more

- moved

- much

- multiple

- must

- necessary

- Need

- New

- no

- nodes

- normal

- noted

- nothing

- now

- obvious

- of

- off

- often

- on

- opportunities

- or

- order

- Other

- out

- over

- pandemic

- part

- parts

- Pay

- PCs

- per

- period

- periodic

- perspective

- PHIL

- phones

- plans

- plato

- Plato Data Intelligence

- PlatoData

- Point

- position

- Predictable

- previously

- Prices

- Principal

- Prior

- problems

- process

- Produced

- Production

- profitability

- projected

- Projection

- projects

- prospect

- published

- qualification

- Quarter

- reach

- reaching

- recovery

- reduces

- reduction

- remains

- report

- represents

- restricted

- result

- retailer

- retailers

- revenue

- roughly

- s

- S&P

- S&P Global

- Safety

- Said

- sale

- sales

- same

- Santa

- Scarcity

- Second

- seem

- sees

- sell

- semiconductor

- Semiconductors

- senior

- set

- shook

- shortage

- shortages

- significant

- Simple

- single

- Sitting

- SIX

- Six months

- sold

- some

- Soon

- Space

- Stage

- steady

- stock

- stream

- such

- suppliers

- supply

- supply chain

- Supply Chain Challenges

- Supported

- Survived

- systemic

- Systems

- team

- Teens

- than

- that

- The

- their

- Them

- then

- There.

- this

- this year

- those

- though?

- threats

- three

- time

- to

- toward

- towards

- trajectory

- TURN

- type

- types

- u.s.

- unforeseen

- unique

- units

- until

- us

- Usage

- use

- used

- using

- value

- vehicle

- Vehicles

- Versus

- virtually

- visible

- wait

- Waiting

- war

- was

- we

- were

- What

- when

- which

- while

- wholesale

- will

- with

- Woods

- worker

- Worst

- would

- year

- zephyrnet