(Editor’s note: In recognition of the Juneteenth holiday, TheDetroitBureau.com is highlighting one of the most influential Black pioneers in the auto industry: C.R. Patterson.)

There are many forgotten automakers, companies that existed for a few years before fizzling out. Truthfully, there were thousands, yet only one, owned and run by Blacks: C.R. Patterson & Sons, which launched its first model, the Patterson-Greenfield, in 1914.

It’s an era when President Woodrow Wilson segregated federal offices, separating toilets in the U.S. Treasury and the Interior Department, which the administration defended as being beneficial to Blacks.

It’s a time when D.W. Griffith’s movie “Birth of a Nation” was seen as legitimate entertainment, despite glorifying the Klu Klux Klan. In 1908, when boxer Jack Johnson became the first Black man to capture heavyweight champion of the world, fans began looking for “The Great White Hope” – a white fighter who could defeat him. Seven years later, it happened after 26 rounds.

Given such inherent racism, it’s miraculous even one Black-owned car company existed.

America’s only car built by a Black-owned automaker

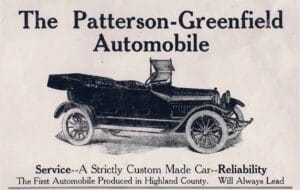

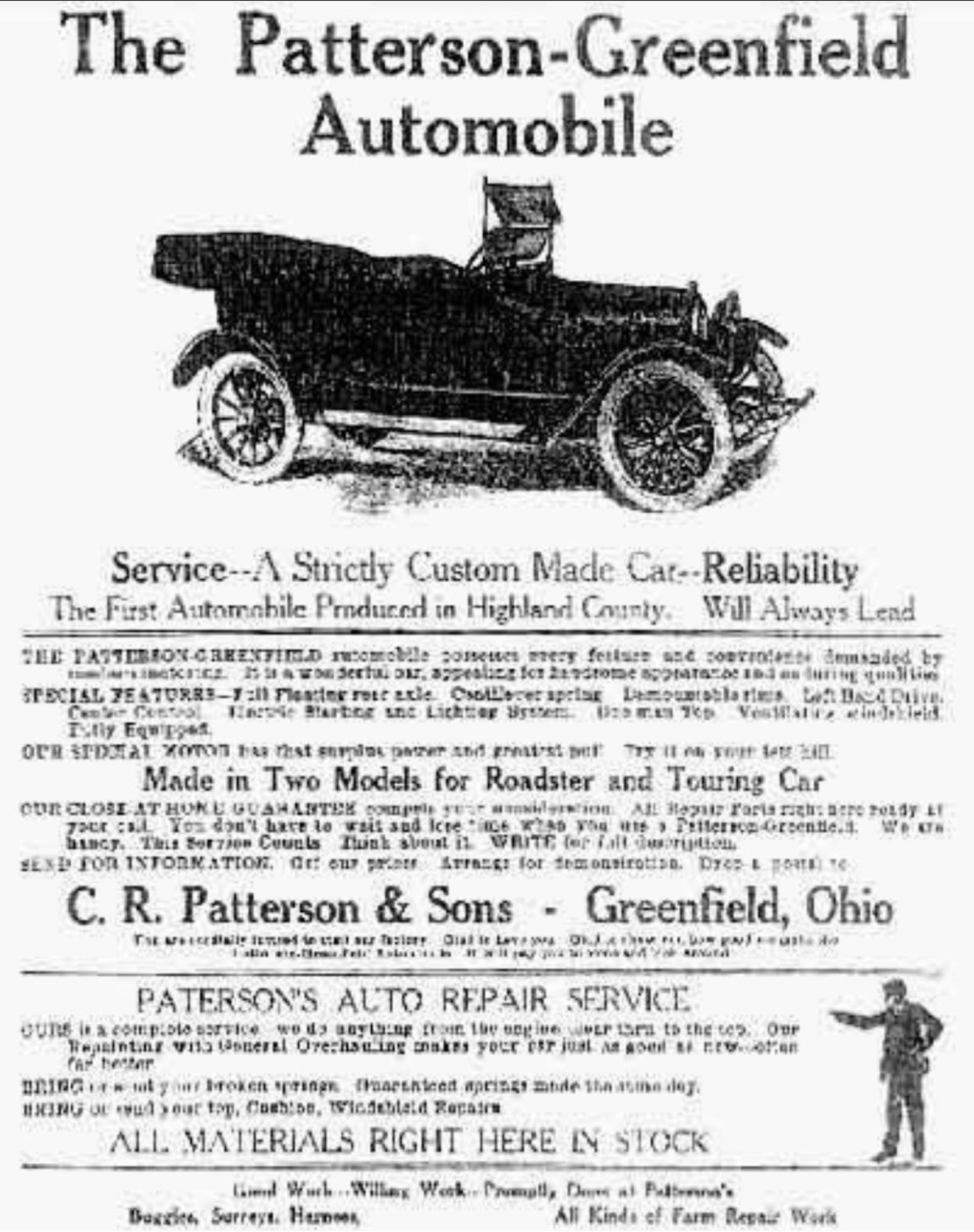

While carriagebuilders are experts at their craft, the engineering it takes to produce a car and its many parts is immensely challenging. So, it’s not surprising that the car, the Patterson-Greenfield, used off-the-shelf parts. Its purchased steel frame had a 108-inch wheelbase, with Patterson completing the wood-framed bodies. Other purchased parts included cantilever springs, the full-floating rear axle, demountable rims, lighting, ventilated windshield and, most importantly, the engine.

Some sources claim Pattersons were powered by a 30-horsepower 4-cylinder Continental engine. Yet company ads talk of engines made by Golden, Belknap & Swartz, or G.B. & S., a Detroit engine builder for small automakers from 1910 through 1924. The L-head 4-cylinder produced 22.5 horsepower, slightly more than a Ford Model T, and was matched with a 3-speed manual transmission with reverse.

Debuting in 1914 as a closed touring car or open roadster, prices ranged from $685 to $850 (or $17,918 to $22,235 adjusted for inflation), and it was sold as “the only Negro Automobile Manufacturing Concern in the United States.”

Yet by 1917, after as many as 150 cars were built, production shut down. What happened?

An unlikely beginning leads to surprising success

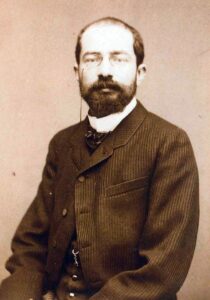

Like many early car companies, the story starts in 19th century, with Charles Richard Patterson, or C.R., for short.

Born on a Virginia plantation in 1833, it isn’t known how Patterson got to Greenfield, Ohio by 1850, a town with strong abolitionist sympathies, home to one of America’s earliest abolition societies and a well-known stop on the Underground Railroad.

Here, C.R. flourished as a Blacksmith, a common skilled trade for Blacks as better jobs were reserved for whites. Working for carriagemaker Dines & Simpson, he rose to shop foreman, working and supervising an integrated workforce. In 1864, he married; six children followed, including Frederick, Samuel and Postell, all of whom would work alongside their father.

By 1873, C.R. formed his own business with a white man who had helped secure the company’s initial financing. J.P. Lowe and Co. proved successful until the Panic of 1893, which killed many businesses. Lowe, who had bankrolled the company, wanted out. C.R. obliged, renaming the company C.R. Patterson & Sons.

Seven years later, the company boasted an integrated workforce of 50, building 28 models priced from $120 to $150, as well as a Mail Delivery Buggy and the School Wagon.

A new era

Then, in 1910, C.R. died, and Frederick took the reins.

Times were changing. There was now one car for every 800 people, a huge change from the year before, when there was one car for every 65,000. The company was already servicing automobiles as a sideline. To Frederick, who graduated from Ohio State University where he was the first Black to play on the football team and served as class president, now was the time to build their own car.

Frederick pondered what it should be. Their shop was not a custom coachbuilder, nor a mass producer. It was somewhere in-between. And that’s what he wanted from his new car. Also, it had to be practical for family use; large, but not too large. Finally, it had to be reasonably priced, yet contain the quality the company was known for.

It proved successful, for a time.

So what went wrong?

Patterson produced his car through 1917. But a World War was raging and raw material costs were rising. Being Black-owned, the company was blocked from obtaining the financing needed to expand, so Patterson couldn’t compete with the deep pockets of larger mass producers like Ford, General Motors and Studebaker, which also had a decade’s head start.

Patterson experimented with cars as early as 1902. Had he started then, the year that carriagebuilder Studebaker built its first car, one year before Ford Motor Co. was founded, and six years before GM was established, he might have stood a chance.

The company returns to its roots

Patterson turned to producing custom bodies for commercial vehicles, which the company had successfully done as carriagebuilders. The company supplied school bus bodies across Ohio, West Virginia and Kentucky, as well as the first transit buses in Cincinnati and Cleveland.

It also fabricated insulated cargo trucks, hearses, moving vans, ice, bakery and milk trucks on Chevrolet, Dodge, Ford, Graham, Reo, and International chassis. Frederick’s son, Frederick Jr., oversaw their design.

The company thrived until the death of Frederick in 1932, after which the company slowly declined. New school bus safety standards in 1935 strained the business as the company struggled to compete against larger, better-financed competitors. In the end, a misguided move to Gallipolis, Ohio proved fatal.

By 1939, the company closed.

Today, 156 years after the Civil War’s end, the U.S. is still struggling to reconcile democracy with slavery. That a Black-owned firm, C.R. Patterson & Sons of Greenfield, Ohio, could find success in such a malicious environment over three generations should be held up for the significant accomplishment that it is, and an example of how anyone can overcome adversity.

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- EVM Finance. Unified Interface for Decentralized Finance. Access Here.

- Quantum Media Group. IR/PR Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Data Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- Source: https://www.thedetroitbureau.com/2023/06/a-car-youve-never-heard-of-from-a-company-that-deserves-admiration/

- :is

- :not

- :where

- ][p

- $UP

- 000

- 22

- 26

- 28

- 50

- 65

- a

- across

- Adjusted

- administration

- Ads

- After

- against

- All

- alongside

- already

- also

- an

- and

- anyone

- ARE

- AS

- At

- auto

- automakers

- automobile

- automobiles

- BE

- became

- before

- began

- Beginning

- being

- beneficial

- Better

- Black

- blocked

- bodies

- build

- builder

- Building

- built

- Bureau

- bus

- Buses

- business

- businesses

- but

- by

- CAN

- capture

- car

- Cargo

- cars

- Century

- challenging

- champion

- Chance

- change

- changing

- Charles

- chassis

- Chevrolet

- Children

- claim

- class

- cleveland

- closed

- CO

- COM

- commercial

- Common

- Companies

- company

- Company’s

- compete

- competitors

- completing

- Concern

- continental

- Costs

- could

- craft

- custom

- Death

- deep

- delivery

- Democracy

- Department

- deserves

- Design

- Despite

- died

- Dodge

- done

- down

- Early

- end

- Engine

- Engineering

- Engines

- Entertainment

- Environment

- Era

- established

- Ether (ETH)

- Even

- Every

- example

- Expand

- experts

- family

- fans

- Federal

- few

- Finally

- financing

- Find

- Firm

- First

- followed

- Football

- For

- Ford

- forgotten

- formed

- Founded

- FRAME

- Frederick

- from

- General

- General Motors

- generations

- GM

- Golden

- great

- greenfield

- had

- happened

- Have

- he

- head

- heard

- Heavyweight

- Held

- helped

- highlighting

- him

- his

- Holiday

- Home

- How

- HTTPS

- huge

- ICE

- immensely

- in

- included

- Including

- industry

- inflation

- Influential

- inherent

- initial

- integrated

- interior

- International

- IT

- ITS

- jack

- Jobs

- Johnson

- jpg

- Kentucky

- known

- large

- larger

- later

- launched

- Leads

- legitimate

- Lighting

- like

- looking

- made

- man

- manual

- manufacturing

- many

- Mass

- matched

- material

- max-width

- might

- Milk

- model

- models

- more

- most

- Motor

- Motors

- move

- movie

- moving

- needed

- never

- New

- nor

- now

- obtaining

- of

- offices

- Ohio

- on

- ONE

- only

- open

- or

- Other

- out

- over

- Overcome

- own

- owned

- Panic

- parts

- People

- pioneers

- plantation

- plato

- Plato Data Intelligence

- PlatoData

- Play

- pockets

- powered

- Practical

- president

- Prices

- produce

- Produced

- producer

- Producers

- Production

- proved

- purchased

- quality

- racism

- raging

- Raw

- recognition

- reserved

- returns

- reverse

- Richard

- rising

- ROSE

- rounds

- Run

- s

- Safety

- School

- secure

- seen

- segregated

- separating

- seven

- Shop

- Short

- should

- Shut down

- significant

- SIX

- skilled

- Slowly

- small

- So

- sold

- somewhere

- son

- Sources

- standards

- start

- started

- starts

- State

- States

- steel

- Still

- Stop

- Story

- strong

- Struggling

- success

- successful

- Successfully

- such

- supplied

- surprising

- takes

- Talk

- team

- than

- that

- The

- the world

- their

- then

- There.

- thousands

- three

- Through

- time

- to

- too

- took

- touring

- trade

- transit

- treasury

- Trucks

- Turned

- u.s.

- U.S. Treasury

- United

- United States

- university

- unlikely

- until

- use

- used

- Vehicles

- virginia

- W

- wanted

- war

- was

- WELL

- well-known

- went

- were

- West

- West Virginia

- What

- when

- which

- white

- WHO

- Wilson

- with

- Work

- worked

- Workforce

- working

- world

- would

- Wrong

- year

- years

- yet

- zephyrnet