Thousands of companies trumpet tree-planting programs as downpayment toward their carbon emissions debt, yet few are taking adequate steps to address deforestation in their supply chains.

That’s one high-level takeaway from a recent analysis by CDP, the disclosure nonprofit that collects and analyzes corporate emissions and other sustainability data. The organization started collecting deforestation data in 2017, when barely 200 companies completed the questionnaire. Last year, more than 1,000 companies reported their deforestation management practices — including household names Cargill, L’Oreal and Kimberly-Clark.

The biggest mic drop moment? The CDP analysis states that, on average, each reporting company is risking $300 million by failing to address deforestation, while it would take just an average of $17.4 million for each to respond and address practices that reduce tree-cutting activities.

A no-brainer

The case for preventing deforestation is clear. Globally, trees extract 7.6 billion metric tons of CO2 emissions per year, the equivalent of the entire U.S. and European Union’s fossil fuel and industry emissions in 2021. Meanwhile, the clearing of forests accounts for between 12 and 20 percent of total greenhouse gas emissions annually.

That narrative is why thousands of companies support tree-planting programs. There’s Microsoft’s E-tree program, which plants trees in Kenya. The Trillion Trees Project by 1t.org is driven by pledges from AstraZeneca, Capgemini, Mastercard, Nestle, PepsiCo, Salesforce, SAP, Shell, Suzano, Unilever and UPS — and aims to plant 1 trillion trees globally by 2030. Many other companies are investing in reforestation to reach their net-zero commitments.

But against that backdrop, few companies have developed effective deforestation strategies, according to the CDP analysis. Here are three big indicators of that shortcoming:

1. Barely any companies map forest-related risks through their entire supply chain

Just 3 percent of companies that reported deforestation data to CDP are evaluating and tracking whether their supply chains are contributing to deforestation. And only 12 percent monitor their deforestation footprint across their entire value chain. More than a third of those reporting to CDP do not engage their suppliers at all on this subject.

Part of stopping deforestation will require investing in tracking and transparency — deploying technology, labor and verification approaches that can accurately and confidently tell buyers where an input comes from and if it’s linked to deforestation. Engaging suppliers is a crucial part of that process, and according to the CDP report, this practice is still relatively limited.

As an example of a possible best practice, CDP highlights cattle products producer Maisons du Monde, which uses the Leather Working Group standard to track and confirm that the tanning facilities it sources from are operating responsibly without causing deforestation.

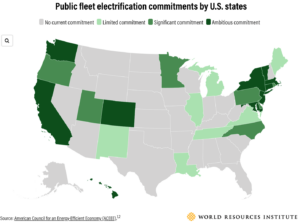

2. North American companies are behind, even though they are the most exposed

North American companies lag their counterparts in Europe, Asia and Latin America (including South America) when it comes to being engaged in monitoring and encouraging no-deforestation activities, according to the CDP report. That reflects, in part, a lack of strong U.S. regulation related to tree cutting.

According to the CDP report, only 29 of 454 commodities sourced by North American companies are covered by timebound no-deforestation public commitments — meaning that businesses have taken the step of pledging to end deforestation practices in their supply chains by a certain date (usually around 2030 or 2050). Only 1 percent of the reporting North American companies supported a rigorous forest-related risk assessment, and no North American participants reported supporting direct suppliers with financial or technical assistance to implement no-deforestation management policies.

That’s ironic considering that North American companies are among those most exposed to risk, as their supply chains extend all over the world in regions where deforestation is a big concern, according to Simon Fischweicher, head of corporations and supply chains for CDP North America.

“Because the U.S. and Canada have some of the larger companies in the world, particularly in sectors that have significant exposure to the commodities that are driving deforestation — the amount of soy, palm timber and beef — they’re very exposed,” he said.

These companies are far removed from the places where tree-cutting is occurring, making it harder for them to evaluate and control the situation — especially compared to Latin American countries dealing more directly with suppliers in regions at high risk for deforestation.

Europe is leading other regions when it comes to ending deforestation. A new law on deforestation-free products approved in May bans the sale of a few commodities — coffee, cocoa, beef, soy, palm oil, rubber and timber — if their production is linked to deforestation. The law, which takes effect in 18 months, will force companies operating in Europe to prove that their supply chains are not contributing to the destruction of forests and is forcing them to toughen their no-deforestation practices.

3. Retail is failing at putting deforestation commitments into practice

As sectors go, retail is performing the worst at taking action on deforestation, based on the companies reporting to CDP. Only about one in every 10 retailers (including grocery stores) has a public no-deforestation policy or has promised to stop converting natural land to agricultural plots.

And according to the report, few of these commitments are backed by specific deadlines or detailed goals, certifications, traceability initiatives or compliance activities. What’s more, few retail sector companies are performing comprehensive risk assessments or tracking deforestation, let alone moving to stop it. The report suggests retailers need to start turning governance and policies into action, but the analysis doesn’t outline how retailers can do this.

- SEO Powered Content & PR Distribution. Get Amplified Today.

- PlatoData.Network Vertical Generative Ai. Empower Yourself. Access Here.

- PlatoAiStream. Web3 Intelligence. Knowledge Amplified. Access Here.

- PlatoESG. Automotive / EVs, Carbon, CleanTech, Energy, Environment, Solar, Waste Management. Access Here.

- BlockOffsets. Modernizing Environmental Offset Ownership. Access Here.

- Source: https://www.greenbiz.com/article/3-ways-companies-fall-short-addressing-deforestation

- :has

- :is

- :not

- :where

- 000

- 1

- 10

- 12

- 20

- 200

- 2017

- 2021

- 2030

- 2050

- a

- About

- According

- Accounts

- accurately

- across

- Action

- activities

- address

- addressing

- against

- Agricultural

- aims

- All

- alone

- america

- American

- among

- amount

- an

- analysis

- analyzes

- and

- Annually

- any

- approaches

- ARE

- around

- AS

- asia

- assessment

- assessments

- Assistance

- At

- average

- backdrop

- backed

- Bans

- based

- because

- Beef

- behind

- being

- BEST

- between

- Big

- Biggest

- Billion

- businesses

- but

- buyers

- by

- CAN

- Canada

- Capgemini

- carbon

- carbon emissions

- Cargill

- case

- causing

- certain

- certifications

- chain

- chains

- clear

- Clearing

- co2

- co2 emissions

- Coffee

- Collecting

- collects

- comes

- commitments

- Commodities

- Companies

- company

- compared

- Completed

- compliance

- comprehensive

- Concern

- confidently

- Confirm

- considering

- contributing

- control

- converting

- Corporate

- Corporations

- countries

- covered

- crucial

- cutting

- data

- Date

- dealing

- Debt

- deforestation

- deploying

- detailed

- developed

- direct

- directly

- disclosure

- do

- Doesn’t

- driven

- driving

- Drop

- each

- effect

- Effective

- Emissions

- encouraging

- end

- engage

- engaged

- engaging

- Entire

- Equivalent

- especially

- Ether (ETH)

- Europe

- European

- evaluate

- evaluating

- Even

- Every

- example

- exposed

- Exposure

- extend

- extract

- facilities

- failing

- Fall

- far

- few

- financial

- Footprint

- For

- Force

- fossil

- Fossil fuel

- from

- Fuel

- GAS

- Globally

- Go

- Goals

- governance

- greenhouse gas

- Greenhouse gas emissions

- grocery

- Group

- harder

- Have

- he

- head

- here

- High

- high-level

- highlights

- household

- How

- HTTPS

- if

- implement

- in

- Including

- Indicators

- industry

- initiatives

- input

- into

- investing

- IT

- jpg

- just

- kenya

- labor

- Lack

- Land

- larger

- Last

- Last Year

- Latin

- latin america

- Latin American

- Law

- leading

- Limited

- linked

- Making

- management

- many

- map

- mastercard

- May..

- meaning

- Meanwhile

- metric

- Microsoft

- million

- moment

- Monitor

- monitoring

- months

- more

- most

- moving

- names

- NARRATIVE

- Natural

- Nature

- Need

- net-zero

- New

- no

- Nonprofit

- North

- north america

- occurring

- of

- Oil

- on

- ONE

- only

- operating

- or

- organization

- Other

- outline

- over

- palm

- part

- participants

- particularly

- pepsico

- per

- percent

- performing

- Places

- plants

- plato

- Plato Data Intelligence

- PlatoData

- policies

- policy

- possible

- practice

- practices

- preventing

- process

- producer

- Production

- Products

- Programs

- project

- promised

- Prove

- public

- Putting

- RE

- reach

- recent

- reduce

- reflects

- regions

- Regulation

- related

- relatively

- Removed

- report

- Reported

- Reporting

- require

- Respond

- retail

- retailers

- rigorous

- Risk

- risk assessment

- risking

- risks

- rubber

- s

- Said

- sale

- salesforce

- sap

- sector

- Sectors

- Shell

- Short

- significant

- Simon

- situation

- some

- sourced

- Sources

- South

- South America

- specific

- start

- started

- States

- Step

- Steps

- Still

- Stop

- stopping

- stores

- strategies

- strong

- subject

- Suggests

- suppliers

- supply

- Supply chains

- support

- Supported

- Supporting

- Sustainability

- Take

- taken

- takes

- taking

- Technical

- Technology

- tell

- than

- that

- The

- the Law

- the world

- their

- Them

- There.

- These

- they

- Third

- this

- those

- though?

- thousands

- three

- Through

- to

- Total

- toward

- Traceability

- track

- Tracking

- Transparency

- tree

- Trees

- Trillion

- Turning

- u.s.

- unilever

- UPS

- uses

- usually

- value

- Verification

- very

- ways

- when

- whether

- which

- while

- why

- will

- with

- without

- working

- Working Group

- world

- Worst

- would

- year

- yet

- zephyrnet